This summer, Professor and Chair of Chemistry Keri Colabroy learned that the National Science Foundation (NSF) had granted $315,000 to Muhlenberg to support her research. The project, a collaboration with Rhodes College Professor and Chair of Chemistry Larryn Peterson, is about turning carbon from natural sources, like tree bark, into useful materials, like antibiotics, using powerful enzymes called dioxygenases.

Sixty Muhlenberg students have worked on the project since it began with support from another $294,000 NSF grant in 2017. Some of them came to the project through Experimental Biochemistry, a course that works on small pieces of the project during class time. Others have joined Colabroy’s lab, which works on the project more extensively during the academic year and over the summer. The research has resulted in five peer-reviewed publications, including one that was published in the journal ACS Omega in July, with 16 unique Muhlenberg student co-authors, and more than a dozen presentations by Muhlenberg students at national meetings.

“I think research is the best teaching I do. I have not observed any other method by which I see such profound transformation in students,” says Colabroy, who has also coordinated summer research across disciplines at Muhlenberg for the past 15 years. “The power of being able to look at a problem and instead of being afraid of trying to solve it, you have a willingness to try this or try that … I can’t provide a student with a better set of tools. I’ve been an adult now for some years, and that is the skillset that I use over and over and over again.”

“I think research is the best teaching I do. The power of being able to look at a problem and instead of being afraid of trying to solve it, you have a willingness to try this or try that … I can’t provide a student with a better set of tools.”

Colabroy came to Muhlenberg in 2005, choosing the institution for its teaching-focused, close-knit faculty community. She wanted to build relationships with students in a way that’s possible only at small liberal arts institutions, both in the classroom and in the lab. She teaches courses across chemistry and biochemistry; this semester, one of them is Organic Chemistry.

“Organic chemistry, it was my first love — it is what captivated my heart and made me a chemist,” she says. “Teaching that class for me is walking down memory lane every time. I just love that atmosphere and what you learn in that class.”

A popular course she teaches for non-majors is Kitchen Chemistry; the accompanying textbook she co-authored was just updated and re-released. She’ll offer a version of the course in the spring that will be team-taught with Lecturer of Italian and French Daniela Viale, focusing on Italian food and culture. Kitchen Chemistry includes a lab component in which students cook; the final project requires students to choose something they’ve never made before and to try to cook it, using techniques they haven’t done in the lab, by applying the principles of chemistry.

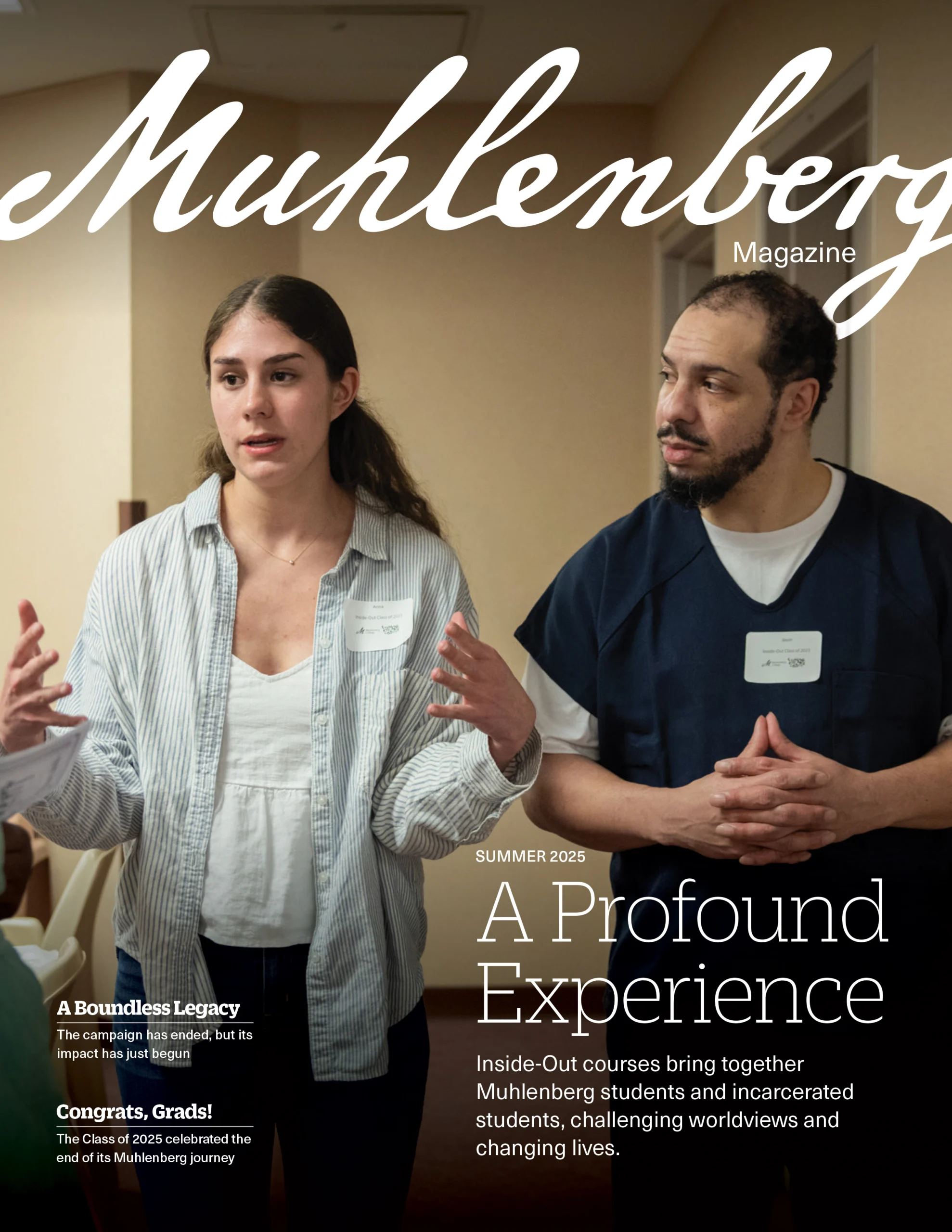

Colabroy directs some Experimental Biochemistry students in the lab this fall.

“The problem-solving logic that we apply in chemistry is valuable to everyone,” she says. “In General Chemistry, you’re in a lab, you have to wear goggles. It feels like, ‘I can’t do this. This is dangerous.’ [Kitchen Chemistry] lowers the barriers to entry. It removes some fear and provides some motivation, because who doesn’t want to eat cookies when you’re done?”

“The problem-solving logic that we apply in chemistry is valuable to everyone.”

Another way Colabroy has worked to lower barriers to entry is through a mentorship program for underrepresented students in STEM, which launched in 2023 with the help of a $266,280 grant from the Arthur Vining Davis (AVD) Foundations. She and Associate Professor of Biology Giancarlo Cuadra head up the program, which gets incoming students into the lab early — before or during their first year — and pairs them with faculty, peer, and alumni mentors. These early research and mentorship experiences can help these students persist in the sciences.

“Research is entry-level. Classes don’t always feel entry-level. Maybe you start in General

Chemistry or Intro to Biology and you feel like you need to have known a lot already to get to that table,” she says. “Research is a lot more entry-level, because you can do [science] long before you understand. Most of us drive cars without understanding at all how cars work. Is driving a car the prerequisite to wanting to understand how cars work? Maybe. So for students who have an interest in understanding science, doing the science is a real gateway. It’s an entry point, and it is a powerful one.”

“If we ask today’s employers what they want, they want problem-solvers who can work in teams, and I’m like, ‘This is what I do.’”

The other major skill research teaches, Colabroy says, is the ability to collaborate with others and work as a team. The six returning students in her lab this fall recently demonstrated their aptitude with this: Their experiments take four to five days to complete, and each day requires students in the lab to keep the experiment moving. When one student hurt her ankle and had to go to the emergency room, the others quickly stepped in to figure out who could cover for her until she was back on her feet.

“If we ask today’s employers what they want, they want problem-solvers who can work in teams, and I’m like, ‘This is what I do,’” Colabroy says. “Science is cool and enzymes are fun, but nine times out of 10, what we’re doing in the lab is solving problems, and those skills are translatable.”