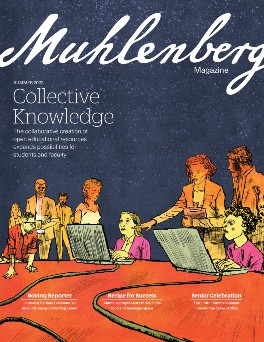

Knowledge in Action

Does AI still need humans? Is fentanyl airborne? How did certain vaccines and monuments become so polarizing? Questions like these lead to engaging discussion directly tied to issues currently facing our nation and world. It all begins with timely, innovative course creation by Muhlenberg faculty.

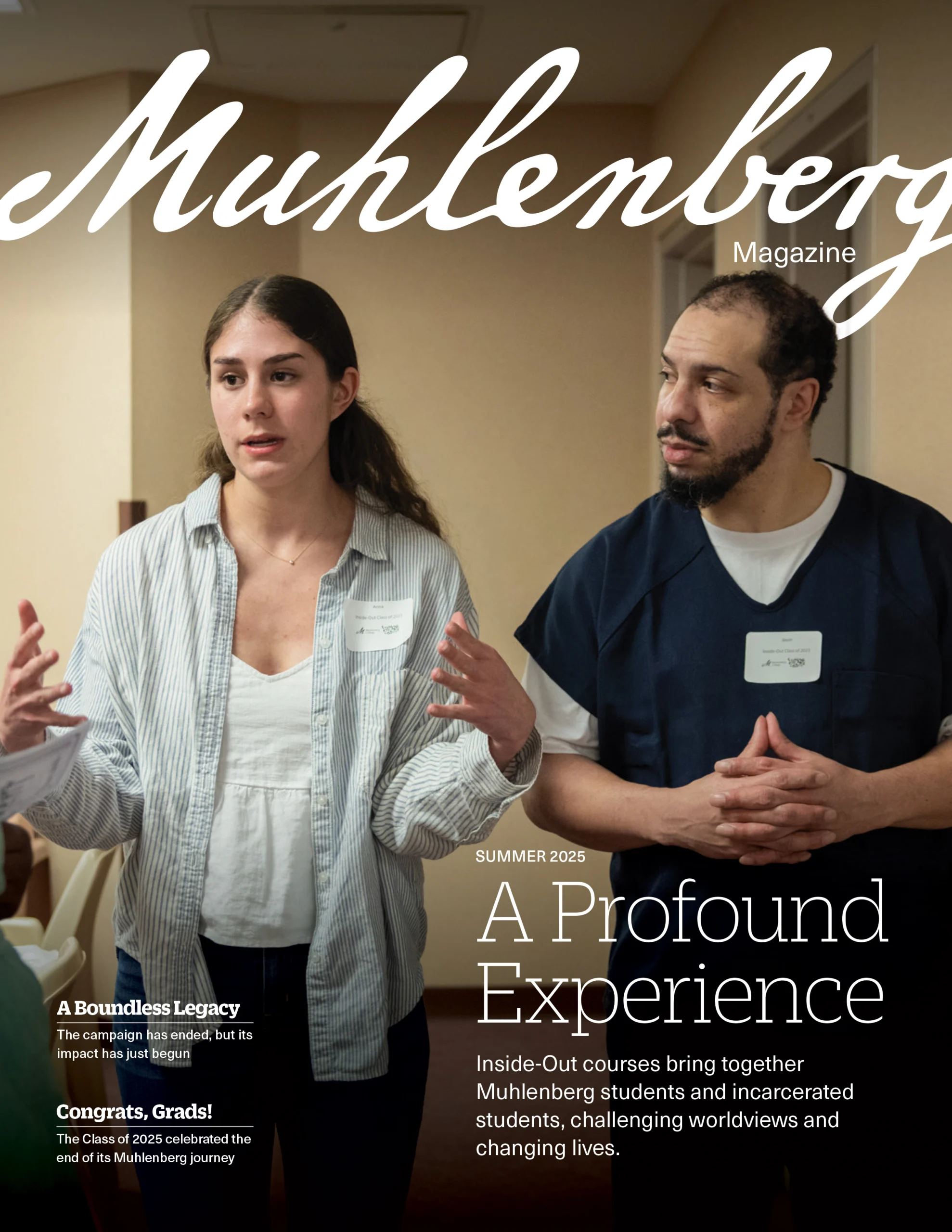

In early September, Associate Professor of History Jacqueline Antonovich was teaching about Jacobson v. Massachusetts, a Supreme Court case decided in 1905 that ruled it was constitutional for states to impose vaccine mandates. The discussion was part of Vaccination Nation: Historical and Public Health Perspectives, a new integrative learning course Antonovich co-developed and is co-teaching with Associate Professor of Public Health Kathleen Bachynski.

A student asked whether the decision was still in effect, because she’d never seen anyone fined or imprisoned for failing to be vaccinated. As Antonovich explained that each state has different levels of interventions — that one state may have strict vaccination requirements to attend public schools, for example, while another may allow for more kinds of exemptions — another student raised her hand.

“I just got a news alert that Florida is getting rid of all vaccination requirements,”

the student shared.

“The way that a student was able to connect a 1905 law that we were just talking about to a news alert — to me, that is what is so special about this class,” Antonovich says.

Vaccination Nation is one of several especially timely courses being taught this fall at Muhlenberg. A liberal arts education empowers students to connect the dots between what they’re learning in the classroom and what’s happening beyond it. These courses, developed by Muhlenberg’s innovative faculty, do this explicitly, and student demand for such courses is high.

“One of Muhlenberg’s greatest strengths is the creativity of our faculty, who design courses that speak directly to the issues shaping our world today,” says Provost Laura Furge. “These courses don’t just deliver content — they invite students to engage deeply, make connections across disciplines, and see the relevance of their education in real time. Muhlenberg faculty are continually designing new classes with not only timely themes but assignments and experiences that prepare students to critically examine complex issues.”

Step inside the classrooms of four such courses challenging students this fall.

Vaccination Nation

Bachynski had the idea for a course on vaccines during the COVID-19 pandemic. In panels and classrooms before and after campus closed, she was fielding lots of questions about vaccines, so many that she added a session to her Issues in Public Health class about them.

“I felt I couldn’t do vaccines justice in one class session, and I definitely couldn’t do them justice alone,” Bachynski says. “I knew Jacki was an expert in the history of medicine, and I thought she would be the perfect person to brainstorm this idea with.”

The pair received a summer course development grant from Muhlenberg to build Vaccination Nation, which walks students through different epidemics, from smallpox to COVID, with the history perspective first and the public health perspective second.

“To our knowledge, this is the first time a class like this has ever been taught,” Bachynski says. “We couldn’t use another syllabus as inspiration — we had to create this out of whole cloth from our own expertise and our own assessment of what themes we thought would resonate.”

The course includes a semester-long group project in which students choose an epidemic and a vaccine and conduct research on it from a national, local, and hyperlocal perspective, using The Muhlenberg Weekly archives and other primary sources to see how campus was affected by these diseases. These projects will be on display next spring in Trexler Library’s Rare Books Room. Additionally, each group must create a modern-day public health campaign to educate the masses about the same vaccine, whether that’s a series of social media messages, a TikTok video, or a podcast.

To understand what the course looks like in practice, take the rabies module: Antonovich begins by placing rabies in its historical context as one of the scariest diseases. Without the vaccine, it is 100% fatal in humans, and that fear of rabies is what drove, for example, folklore about vampires and werewolves. The rabies vaccine, developed by Louis Pasteur and first administered in 1885, marked the beginning of a period of great innovation in public health.

During Bachynski’s portion of the course, students learn about today’s rabies post-exposure prophylaxis, which includes a modernized vaccine and rabies immunoglobulin. This treatment can cost thousands of dollars if you don’t have insurance (and can cost hundreds even with coverage). Public health experts (Bachynski included) recommend pursuing the treatment if you even wake up in a room with a bat, because it is technically possible to be bitten in your sleep and not realize it. However, one of the papers students read, written by economists, debates whether that should be a universal recommendation.

“They did the math and it’s something like you’d have to vaccinate a million people [who’d woken up with a bat] to prevent one rabies death,” Bachynski says. “It’s honestly really rare to be bitten by a bat and not know it. It raises some really profound ethical questions about what our actual policy would be, so that’s the kind of thing I thought would be useful for our students to talk about and grapple with.”

And students from many disciplines are eager to grapple with such questions: The 20 students in the course (which had 30 more on the waitlist) include not only history and public health majors but neuroscience, business administration, biology, and finance students as well. The course makes room for these multiple disciplinary perspectives as well as multiple perspectives on the historical events and vaccines the course teaches about. For example, smallpox eradication — the only

disease we’ve ever eradicated — is widely celebrated as a public health victory. However, fewer people are aware that, to achieve eradication, some people in India and Bangladesh were held down and forcibly vaccinated, “one of the worst violations of civil liberties,” Bachynski says.

“I can show you all the epidemiological data about how vaccines work and the impact they have on the trends of various diseases, but what I alone can’t tell you is what to do with that information,” Bachynski says. “I think we have an obligation, if we’re asking people to get vaccinated, to provide people information about vaccines and to do that in a way that is interdisciplinary.”

“To our knowledge, this is the first time a class like this has ever been taught. We had to create this out of whole cloth from our own expertise and our own assessment of what themes we thought would resonate.”

— Kathleen Bachynski, Associate Professor of Public Health

“[AI tools] are not autonomous systems. There has never been an autonomous system. Humans are the glue of these systems. People with bodies, real people, are the ones who are giving [them] data. Humans are the flesh and

— Hamed Yaghoobian, Assistant Professor and Director of Computer Science

bone of these systems.”

Human-AI Interaction

Assistant Professor and Director of Computer Science Hamed Yaghoobian first offered Human-AI Interaction, a course for computer science majors, in spring of 2023. At that time, ChatGPT had only been around for a few months. For the final project, students built a language model trained on the satirical news site The Onion and posted it on the communication platform Discord so others could chat with it. It worked, but it was buggy — cutting off in the middle of sentences and so on.

Language model technology has obviously come a long way, so Yaghoobian had to rework the entire course to offer it this fall. One of the papers the class discusses is an MIT Technology Review story about a therapy client who discovered that his therapist was using ChatGPT during a session, typing in what the client was saying to receive guidance on how to respond.

“Students were saying in class the other day that you can choose not to engage with these systems,” Yaghoobian says. “In a lot of cases, people are not given a choice.”

The goal of Human-AI Interaction is to demystify AI, which is now, in some cases, so complex that the engineers who built certain AI products cannot explain their behavior — “a growing concern,” per Yaghoobian. Students learn the history of artificial intelligence, critique and examine modern AI systems, and get hands-on experience through AI-related projects. For the final project, students must propose a way they can collect data, use that data to build their own custom large language model (LLM), and then critique the output.

The class talks about whose knowledge is captured by AI — that is, the knowledge of people and cultures able to write things down — and whose is therefore missed. They discuss the polarity of the techno-utopianist view of AI and AI doomerism and how neither perspective supports meaningful engagement with these products and the ethical questions they raise. They grapple with the current moment in AI: Big tech is receiving huge amounts of money to develop and deploy these tools, which are being integrated into companies, governments, schools, and beyond with mixed results.

“The job sector, for example: Resumes are being generated by AI, they’re being evaluated by AI, and people get rejected,” Yaghoobian says. “It ends up hurting humans.”

Higher ed is another sector the class discusses. Professors are concerned about the consequences of text generation for essay writing. If students can use a tool to write for them, what happens to writing?

“At Anthropic, they realized that if they feed a lot of AI-generated content to an LLM, it would be a form of ‘cannibalization,’” Yaghoobian says. “If a model is trained repeatedly on its own content, it tends to ‘hallucinate’ more and becomes more confident in presenting those ‘hallucinations’ as facts.”

The bottom line of Human-AI Interaction, at least the 2025 version of the course, is that there is no AI without human interaction: “These are not autonomous systems. There has never been an autonomous system. Humans are the glue of these systems,” Yaghoobian says. “Even ChatGPT, without the humans interacting with this thing, it’s nothing. People with bodies, real people, are the ones who are giving it data.

Humans are the flesh and bone of these systems.”

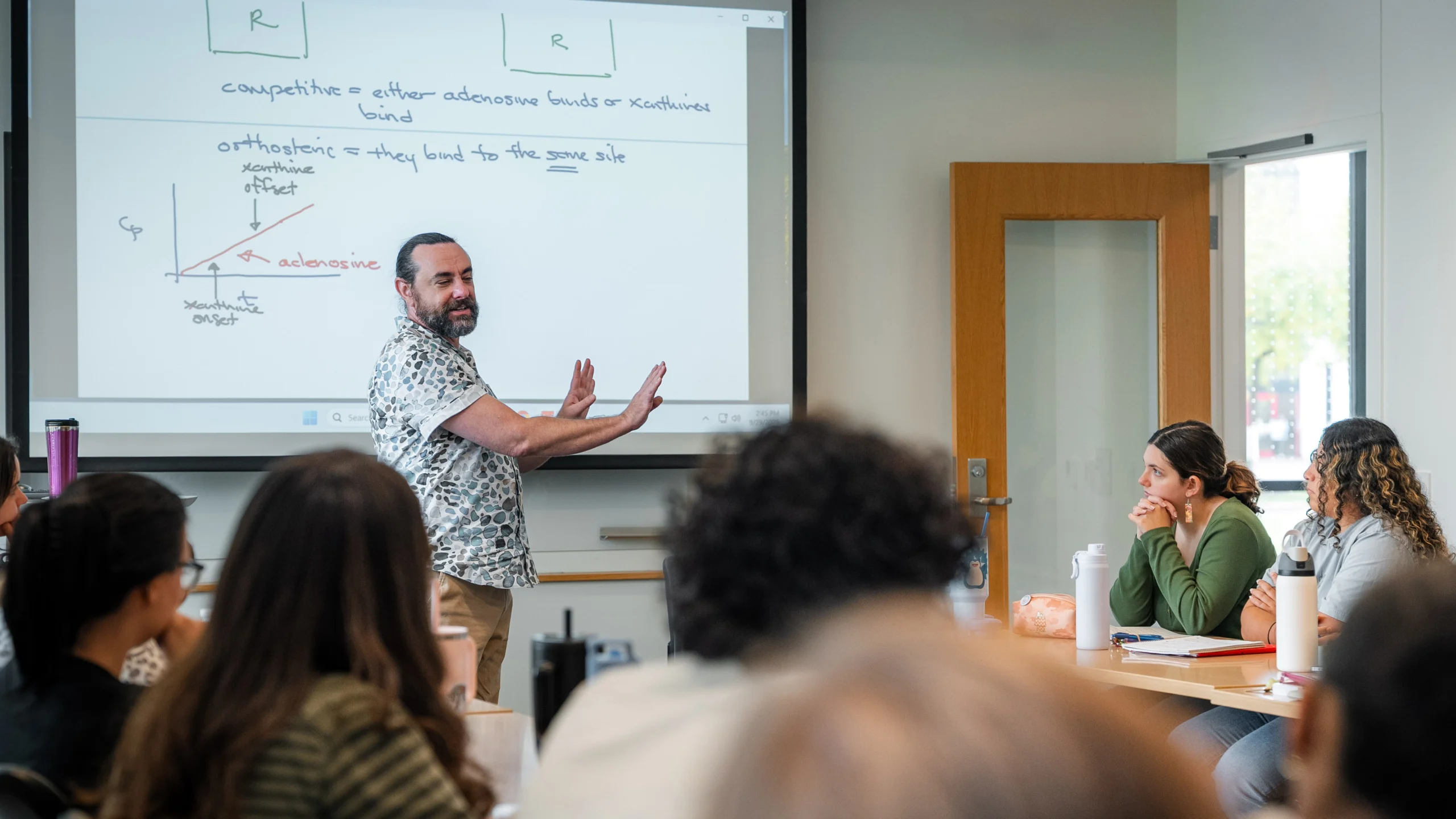

Rethinking Drugs and Drug Abuse

Students in both sections of Stanley Road Professor of Neuroscience Jeremy Teissere’s course Rethinking Drugs and Drug Abuse had seen reports of police officers accidentally being exposed to fentanyl and having serious reactions, including convulsions. In fact, Teissere searched for such stories in class and found a couple examples from the previous few weeks.

The problem with those stories? “[Fentanyl is] not airborne. You’d have to be in dunes upon dunes of fentanyl,” says Teissere, adding that patches are the only way to absorb fentanyl through the skin, and those take hours to take effect. “Unless you inject it or eat it, you cannot be affected by fentanyl.”

Fentanyl also wouldn’t cause convulsions — its effect would be “total sleepiness and cessation of breathing,” he says. It’s possible that fear culture surrounding fentanyl, which is dangerous, is behind these reactions. However, Teissere and other pharmacologists worry that misinformation about fentanyl will make bystanders afraid to intervene if someone is overdosing.

Teissere’s goal for this popular course for non-majors — he’s teaching 24 students in each section, with another 51 on the waitlist — is to empower students to sort through such misinformation. The way drugs are typically taught in public schools and the social narratives people encounter about drugs often do not reflect science, he says, and the goal is to develop scientific literacy in these students.

The course begins with an examination of popular culture, to identify common societal narratives about drugs: “I found out pretty early on in teaching classes like this that if I don’t do this, people are frightened to speak, because if you seem to know something about drugs, it means you take drugs,” Teissere says. “So that stigma hovers over the beginning of this class.”

Then, the class spends some time learning about how the law has addressed drugs throughout U.S. history, including prohibition of alcohol and cannabis, opioid regulations including the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914, and the Controlled Substances Act of 1970, which gives us the drug scheduling we have now.

“This is just a really good example of where the science runs afoul of the policy,” Teissere says, noting that cannabis is still classified as Schedule I (“no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse”) at the federal level but is legal to purchase and use recreationally in 24 states and Washington, D.C.

The students learn the fundamental science behind drugs: what constitutes a dose, how drugs go into and leave the body, how drug tests work. And then, Teissere provides a more in-depth look at four common drugs: alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, and caffeine. For the final project, students split into groups to work on presentations about drugs of their choosing that were not covered in class. In the past, groups have presented about supplements, which aren’t regulated by the Food and Drug Administration; GLP-1 agonists like Ozempic and Wegovy; stimulants like cocaine and methamphetamine; and ketamine, which is now being used to treat chronic pain and unresponsive depression.

The class ends with an oral exam, in which small groups of students meet with Teissere in his office to discuss what they learned in the class, including how, exactly, it made them rethink drugs and drug abuse.

“I don’t care how students rethink drugs and drug abuse. The expectation is that, in some way, they will rethink [them],” Teissere says. “Where drugs and medicines are going to meet them isn’t going to be on an exam. Instead, it’s going to be, their grandmother was given a new medication and she’s frightened to take it, or they have a question about recreational use [of a drug]. They feel empowered, even if they don’t have the answer, to know how to navigate information sources and cut through social narratives to be able to find reliable information.”

“[Students] feel empowered, even if they don’t have the answer, to know how to navigate information sources and cut through social narratives to be able to find reliable information.”

— Jeremy Teissere, Stanley Road Professor of Neuroscience

“One of the goals of the course is to look with fresh eyes at these things that are around us, to notice and to see how we structure our public spaces.”

— Giacomo Gambino, Bormann-Paris Professor of Political Philosophy

Monument Wars

When students in the first-year seminar Monument Wars visited Washington, D.C., at the end of September, they spent the day on a walking tour of 22 monuments, including the Washington Monument, completed in 1884, and the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, built in 1982. The field trip allowed students to experience the direction monuments are generally moving — that is, away from simply being tributes to greatness.

“Monuments becoming more introspective rather than glorifying is an interesting long-term development taking place in the country,” says Tammy L. Bormann ’83 P’16 and Mark J. Paris ’80 P’16 Professor of Political Philosophy Giacomo Gambino, who teaches the course.

A notable exception, he says, is the National Garden of American Heroes the current administration has proposed, which received $40 million in funding from Congress as part of a tax and spending bill passed in July. It would contain 250 statues of a wide variety of Americans, from the Founding Fathers to Billy Graham, Whitney Houston, and Alex Trebek.

“That would be a kind of monument to greatness again,” Gambino says. “That itself is a reaction to what has been clearly a tendency toward looking at the victims of various horrific events rather than simply the heroes [through monuments].”

It’s Gambino’s second time teaching the course, which was inspired by the monument-related controversies that emerged after George Floyd’s killing in May of 2020. Monument Wars is related to a course he’s taught for more than a decade, Politics and Public Space, which includes a week about monuments.

Monument Wars focuses on the U.S. where, broadly speaking, the most common controversies in the south surround Confederate monuments, while those in the north are focused on statues of Christopher Columbus. In fact, one of the course’s earliest assignments involves reading several articles about the debate surrounding a Columbus statue in Syracuse, New York, a city with a large Italian American population that neighbors the Onondaga Nation reservation. Gambino asks students to consider the different sides of the issue and write about the advice they’d give Syracuse’s mayor.

“Part of what I want them to do is to get in the habit of taking positions and then justifying those positions,” Gambino says.

As students begin to consider the Confederate monuments that have generated renewed attention since 2020, many are surprised to learn when they were built: “They went up a generation or two after the Civil War, in the 1890s all the way into the 1920s and even to the 1930s, in the era of Jim Crow,” Gambino says. “These are not just meant to commemorate a historical moment. They were political statements about who’s in charge of this town.”

The class also explores more recent monuments that seek to contextualize the darker sides of American history. Gambino took a road trip through the south to prepare for this course and found some of the most striking examples of this in Montgomery, Alabama. There, the nonprofit Equal Justice Initiative spearheaded the installation of the Legacy Sites, which explore racial injustice in the United States. One of them, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, is an open-air pavilion downtown with more than 800 hanging steel columns, each of which represents a county in the U.S. Etched on each column are the names of Black victims who were lynched in that county.

“They’ve taken an alternative approach,” Gambino says. “It’s not just about taking down the [Confederate] monuments but building a new monumental landscape that could better express values that are consistent with where we want to be today.”

For the final paper, students have two options. They can explain which monument they think is missing from the United States and why it should be added. Or, they can choose an existing monument and explain why and how it needs to be removed or contextualized in order to provide a better understanding of our shared history. They are able to select one of the monuments they learned about in class or one of the tens of thousands of others the class doesn’t cover, including those in students’ hometowns that they may have passed regularly but barely registered.

“One of the goals of the course is to look with fresh eyes at these things that are around us,” Gambino says, “to notice and to see how we structure our public spaces.”