As Platforms Decay, So Do We

When we outsource our thinking to technology, we’re left without critical skills when those platforms decline — and they always do.

Anyone who uses Google search (that is, nearly everyone) knows it has steadily declined in quality over time. Useful search results have been replaced by advertisements and, most recently, AI “answers” that may or may not be accurate. Similarly, Amazon prioritizes sponsored results over relevant ones, and Facebook buries posts from friends and family under boosted content. These degradations are examples of platform decay, or “enshittification,” a term coined by writer Cory Doctorow in 2022.

Once a useful and convenient platform draws a large enough user base to achieve a commanding market share, access to that platform’s users is sold as a product to business customers, usually advertisers. As meaningful competition disappears (Bing, Yahoo, Ask Jeeves; brick-and-mortar book and department stores; Myspace), companies increase prices for access to their users, enshittifying the platform for users and advertisers alike to drive shareholder profit. Platform decay is neither accidental nor passive. It is the result of intentional, profit-driven design.

The harms of platform decay have been framed as matters of inconvenience or economic unfairness. While these are genuine concerns, Michael J. Ardoline, assistant professor of philosophy at Louisiana State University, and I argue in our Ethics and Information

Technology article, “The cognitive and moral harms of platform decay,” that they overlook deeper harms. Enshittification harms our cognitive and moral capacities, making us worse. This is because ubiquitous platforms are not mere tools; they function as extensions (or “scaffolds”) of our thinking, shaping how we think.

“Enshittification harms our cognitive and moral capacities, making us worse. This is because ubiquitous platforms are not mere tools; they function as extensions (or “scaffolds”) of our thinking, shaping how we think.”

Consider how Google search shapes memory and attention. Starting with memory, let’s consider just two kinds: semantic and transactive. Semantic memory is the recall of specific information (remembering a specific mac and cheese recipe) while transactive memory is the recall of where and how to access information (remembering what to search on Google to find said recipe). The authors of “The ‘online brain’: how the internet may be changing our cognition,” published in World Psychiatry in 2019, show that widespread internet use is shifting us away from semantic memory toward transactive memory, with demonstrable neurological effects. Rather than remember the recipe, we just remember how to Google it. For this to be a successful way to remember, the sources and means of access to information must remain reliable. If the platform that scaffolds transactive memory decays, thus resulting in unreliable access, our transactive memory becomes less

successful — or enshittified.

Worse yet, platform decay results in cognitive deskilling, a loss of cognitive capacity from offloading skills to machines, in this case, digital platforms. Reduced reliance on semantic memory means that we become worse at recalling information unaided. Offloading transactive memory results in a diminished ability to find information without relying on faulty (enshittified) tools. In short, not only can we no longer rely on Google search as a way of successfully finding information, but we are also cognitively worse off, even offline.

Enshittification also harms our attentive capacities. As business products, decaying platforms hijack user attention and redirect it toward advertisements. Like memory, attention is a skill. To the extent that platform decay makes us worse at paying attention — for example, by training us to endlessly scroll bite-sized videos and redirecting us from information we care about to sponsored products — platform decay constitutes a cognitive harm.

“Platform decay is the cognitive and moral equivalent of causing minor brain damage to millions of people.”

Attention is also a moral skill. The literature on virtue ethics, a philosophical theory of the good life as centrally involving personal cultivation, establishes that attention is a “meta-

virtue” required for the cultivation of other moral characteristics. Being a good friend, for example, requires noticing distress; personal growth demands focus on our goals. If platform decay rewires us away from these things by bombarding us with irrelevant distractions, then it erodes our ability to pay attention to morally relevant features of our experience and, therefore, degrades our ability to flourish.

If platforms shape how we think, both on- and offline, then their decay is more than an inconvenience: it constitutes cognitive and moral harms, weakening our abilities to remember well, attend well, and cultivate social and personal excellence. Platform decay is the cognitive and moral equivalent of causing minor brain damage to millions of people. While this is already a serious moral concern, it is all the more serious to the extent that platform decay is intentional (even if these harms are not themselves intended).

While Ardoline and I focus on memory and attention, extended enshittification (the degradation of human capacities through platform decay) isn’t limited to these functions. One urgent concern is the increasing use and impending enshittification of AI, especially large language models (LLMs). As people become more reliant on LLMs to, for example, explain ideas, solve problems, write essays, create code, and make art, we risk outsourcing crucial cognitive and moral capacities, such as critical thinking. As these tools become more and more entrenched, they’ll tend toward enshittification and should be expected to result in deskilling — in this case, of our ability to think for ourselves.

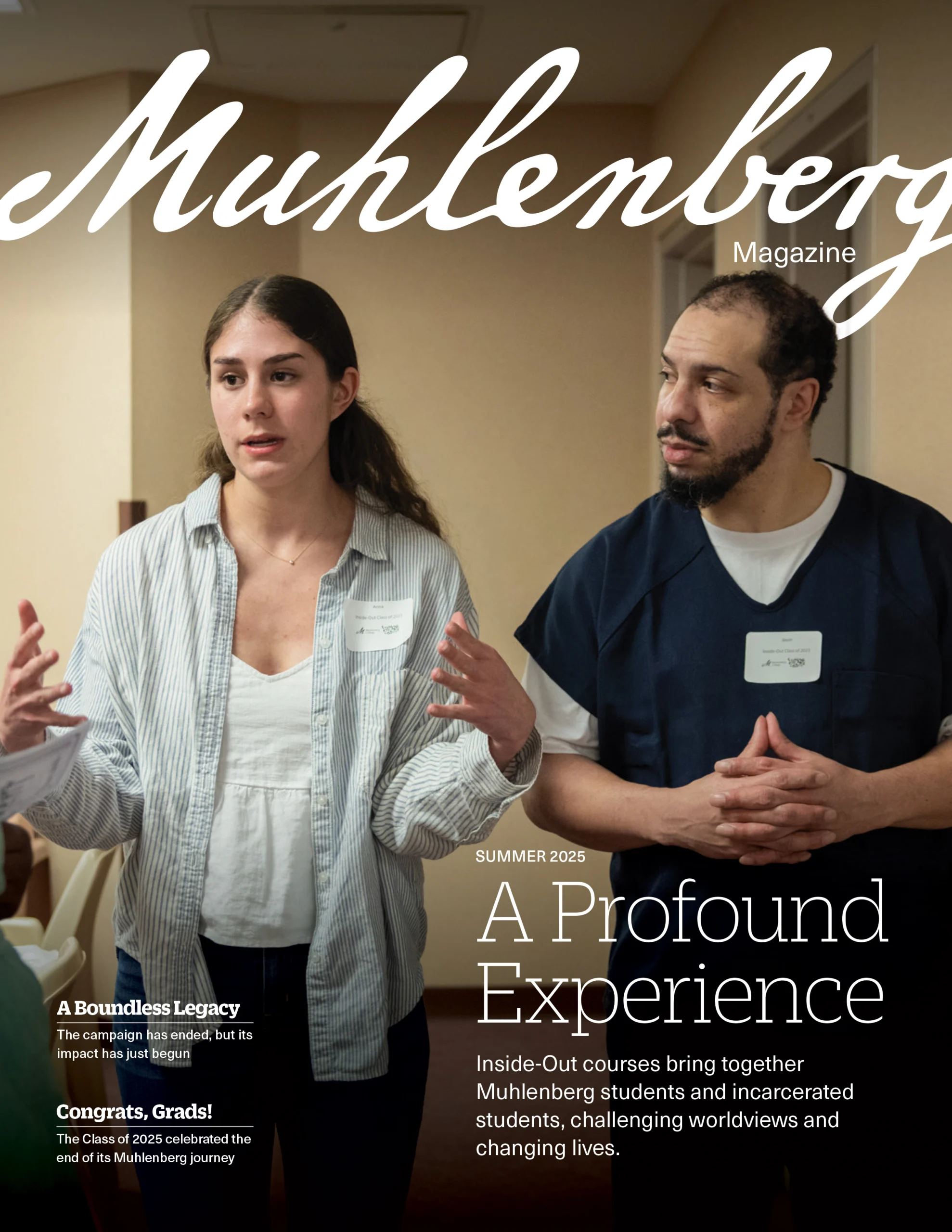

Edward A. Lenzo, Ph.D., is a visiting assistant professor of philosophy at Muhlenberg.