Roving Reporter

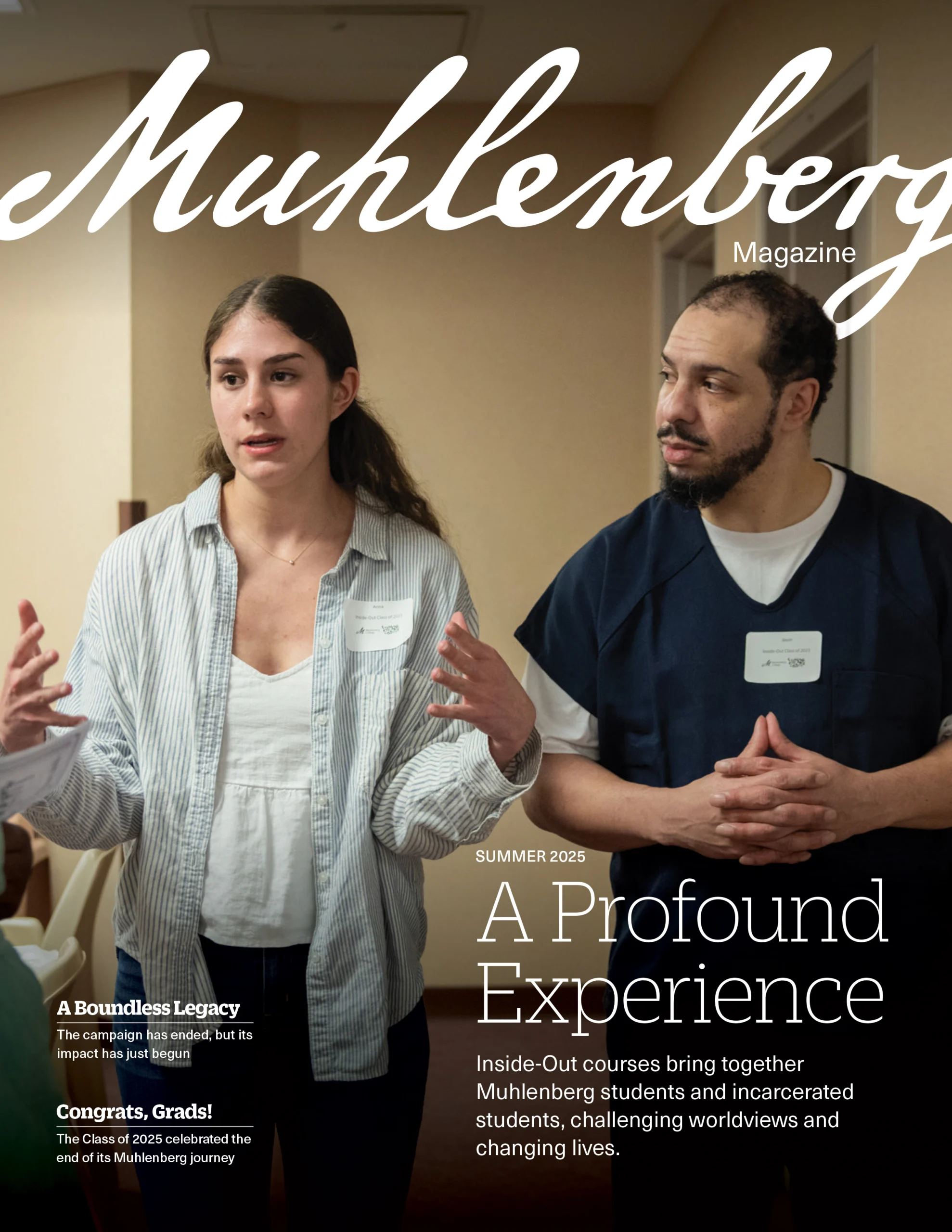

Journalist Barbara Crossette ’63 has traveled to at least 88 countries for her work and was the first woman The New York Times stationed in India as bureau chief, where her reporting won the prestigious George Polk Award.

In 1991, Barbara Crossette ’63 was working as a foreign correspondent for The New York Times in India. That May, she was invited on the campaign trail with former prime minister Rajiv Gandhi and the member of Parliament for the area he was visiting. She met the group at the airport in the city now known as Chennai and crammed into the back of Gandhi’s bulletproof sedan with a reporter from The Gulf News of Dubai and an interpreter. Along the 25-mile route to the night’s main campaign event, Gandhi stopped a few times to greet well-wishers. Some threw flowers and other gifts into the car’s open windows.

It was after 10 p.m. when the group arrived in Sriperumbudur, the village where Gandhi was scheduled to speak. A crowd awaited his arrival. He exited the car and headed toward the open-air stage festooned with bright lights, stopping to chat with people along the way. In her article that appeared in the next day’s Times, Crossette wrote:

A minute or two later, Rajiv Gandhi was dead, killed by a bomb explosion only yards from this reporter.

The May 22 article was the first in a series Crossette produced for the Times about Gandhi’s assassination and the aftermath. Her coverage won the George Polk Award, a prestigious journalism honor, for foreign reporting. Other accolades she earned throughout her career include an award for international reporting from InterAction, a coalition of more than 150 international nongovernmental organizations; a Fulbright Award for contributions to international understanding; the Shorenstein Prize, awarded by research centers at Harvard and Stanford Universities, for writings on Asia that enhanced understanding of the region in the West; and a lifetime achievement award from the United Nations Correspondents’ Association.

Her career at the Times lasted from 1973 to 2002, including foreign correspondent positions in South and Southeast Asia, a year as state department reporter and eight years as UN bureau chief and correspondent. She has taught journalism in the United States and internationally — including to Cambodian journalists covering the Khmer Rouge war crimes tribunal in 2008 — and has authored two State of World Population reports for the United Nations Population Fund, a UN agency focused on reproductive and maternal health. She also served as a Muhlenberg trustee from 2008 to 2014.

Today, Crossette continues to write occasionally on international affairs, covering the United Nations, women’s rights and international news for The Nation and PassBlue.com, a nonprofit media company with more than 15,000 subscribers internationally.

Former Board Chair Richard C. Crist ’77 P’05 P’09 recalls a time he tried to get on Crossette’s calendar when she was a trustee: “After multiple attempts, Barbara responded apologetically that she had been up against a deadline and needed to focus all of her energy on that assignment. Being naturally curious, I inquired about the project. Barbara responded that she was completing an analysis of a speech by the secretary general of the United Nations,” Crist says. “That’s Barbara Crossette in a nutshell: connected to the most interesting and important people around the world and not an egotistical bone in her body.”

Crossette was born in Philadelphia to an eastern European refugee, her mother, and a father whose persecuted Mennonite ancestors from the Rhineland had settled in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, in the 18th century. She grew up in eastern Pennsylvania and was aware of Muhlenberg because of its proximity and the encouragement of her Lutheran mother. Crossette earned a scholarship to Muhlenberg and came to campus in the fall of 1957 with the first coed class to enter the College.

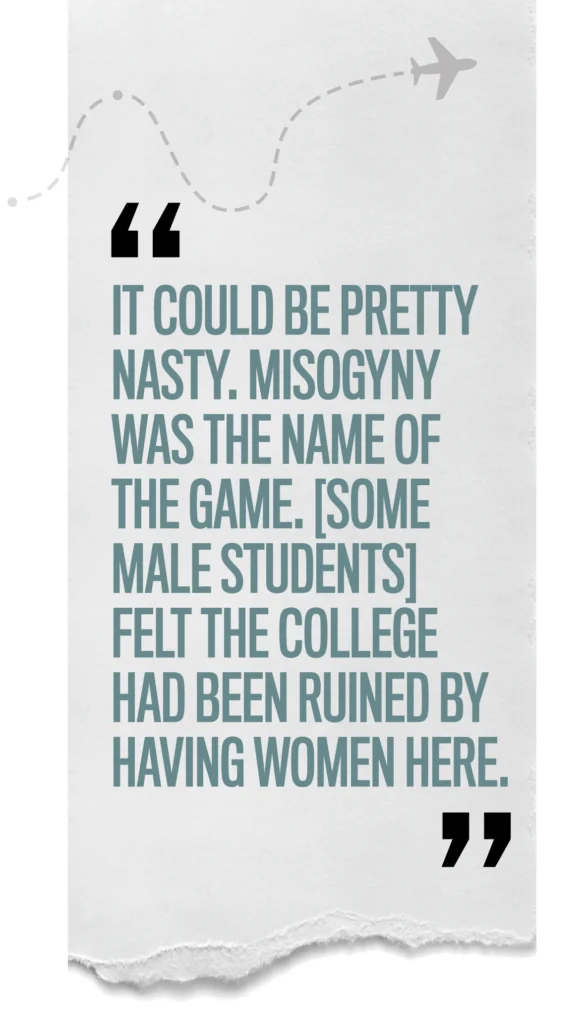

“It could be pretty nasty. Misogyny was the name of the game. [Some male students] felt the College had been ruined by having women here,” she recalls.

Some women in her class found their male classmates’ heckling and interference so upsetting that they became sick or couldn’t eat. Crossette thinks that perhaps being close to home, which she could visit if the campus climate became too much, helped her succeed at Muhlenberg despite the circumstances.

“I remember on behalf of other people what a terrible time it was,” she says. “It was piggish male behavior, was unacceptable and now would not be tolerated.”

At Muhlenberg, she studied history, with a minor in political science. As a writer and editor for The Muhlenberg Weekly, she would go to the print shop in downtown Allentown each week to close the paper. At the Weekly, she learned about the entire newspaper process, from idea generation to typesetting, which would go on to serve her well in her career.

After her third year at Muhlenberg, she married an older Weekly editor who had graduated and entered the Navy and was stationed in Guam. Crossette joined him, living and teaching in the Western Pacific for two years. She also had her son, Jonathan Crossette ’82, while abroad.

She returned to Pennsylvania in 1962 to complete her Muhlenberg degree as a commuter before joining her husband in Colorado, where he was then stationed. She completed a master’s degree in history, with a focus on British history, at the University of Colorado, Boulder. After separating from her husband, Crossette got a grant to do research in England.

During that time, she spent five years in London writing for an education weekly and three in Birmingham writing for The Birmingham Post. England had a large number of immigrants from India and Pakistan, and at that time, racial relations were becoming tense. Her experiences in England contributed to her interest in India, where she would later live and work, and the surrounding region.

In 1973, Crossette returned to the United States to be closer to her parents. She joined the staff of The New York Times, first as a staff editor and writer. The newspaper wasn’t looking for only journalism graduates at that time — they wanted writers with subject-matter expertise to cover any given beat. For example, writers with a legal degree would cover the law; writers with a medical degree would cover medicine. Crossette’s history and political science background, along with her experiences living in England and Guam and traveling around southeast Asia, set her up for a career as a foreign correspondent.

In the early 1980s, she covered the civil wars in Central America, traveling to the region on an as-needed basis and working primarily from New York City. In 1984, she got her first assignment to work full-time abroad, covering 14 countries in Southeast Asia and the Pacific while stationed in Bangkok, Thailand. While she was happy in that position — “Southeast Asia is an easy place to live. The food is good. The people are welcoming,” she says — living and working in India was her dream.

She had first traveled to India on a Fulbright teaching fellowship in 1980. She chose India because she thought it would be interesting (and it was a place where she could lecture in English). She spent six months teaching journalism at Punjab University in northern India, and after that experience, she knew she wanted to live and work in India again.

She got her chance in 1988, when the Times stationed her in New Delhi. She was the first woman the newspaper sent there as bureau chief. In addition to India, she covered more than a half-dozen other countries, including Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal and Bhutan.

The aftermath of the 1991 Gandhi assassination was chaotic: It got out that she was the only Westerner there, and India’s Central Bureau of Investigation wanted to interview her. An American diplomat recommended that she should decline and leave the country, for her safety. Ultimately, she decided to stay, and she shared with the authorities her recounting of the assassination from her perspective. She continued to cover the assassination’s aftermath for a few months.

When she returned to the United States, she took a few months off from the Times. During that period, she traveled to Bhutan and Kathmandu, Nepal, for a book she was working on. The result, So Close to Heaven: The Vanishing Buddhist Kingdoms of the Himalayas, was published in 1995.

After her period of leave, Crossette became the newspaper’s U.S. Department of State correspondent, a role she left after just one year: “I hated Washington,” she says. “It’s a very different life as a foreign correspondent. Abroad, you can talk to people and have lunch with contacts. In Washington, I found the doors were often closed.”

She then spent a couple years as senior editor of weekend operations at the Times, running the paper on the weekend and deciding what would go on the front page. In 1994, she became the UN bureau chief for the Times, a position she held until she left the newspaper in 2002.

“Having traveled and worked in so many countries, often where the UN had a presence, I thought the UN headquarters was a good place to try to look at the connections and differences,” says Crossette, who took time off during this period to travel for a second book, The Great Hill Stations of Asia, which was published in 1998. “I came back to the U.S. with a lot of links to pursue and found a welcome among diplomats who appreciated my knowledge of their home countries and were very helpful.”

After the Times, Crossette taught journalism at Cambodia’s Phnom Penh University for the U.S.-based Independent Journalism Foundation for a few years and was a 2004 International Center for Journalists Knight Fellow in Brazil. She also wrote for the Foreign Policy Association’s Great Decisions discussion program on world affairs.

Through connections she’d made while at the Times, the United Nations Population Fund, a UN agency focused on reproductive and maternal health, asked if she would write a couple of their annual reports. She wrote How Women Cope in Crisis for the agency in 2010 and The World at 7 Billion in 2011. She traveled the world for these projects, including to Haiti after its 2010 earthquake and to Ethiopia, Uganda and back to India to speak specifically with women there.

“I could sit for hours with these women. I developed a lot of sympathy for the lives they had to lead,” says Crossette, who notes that she heard stories of husbands beating their wives for dinner being too hot or too cold and of husbands killing their wives for using contraception. “The reality of their life is hell … Americans aren’t honest enough about this. Everybody here is interested in ‘me’ or ‘my problems.’”

In 2011, she and a former Times colleague founded PassBlue.com, where she has been the senior consulting editor and writer since its inception. In addition to the UN, she covers women’s rights and, more recently, she has produced articles related to the Russian war against Ukraine. During the pandemic, she moved out of Manhattan to Bucks County, Pennsylvania: “I don’t really miss the city as much as I thought I would,” she says. “I’ve been there, done that.”

Crossette has been to a lot of places and done a lot of things: She has reported from at least 88 countries, by her count, including nearly every European country, most of the Latin American countries and obviously, the many countries in Southeast and South Asia where she lived and worked. A friend recently shared with her a list of 60 international cities and asked how many she’d been to. “All of them,” Crossette replied.

She sees her life and her career as one experience building on another, starting with her childhood, spending time with friends and family who were foreigners. That childhood led her to Muhlenberg, which led her to Guam, and every step along the way made a later step possible.

“All these things add up in life,” Crossette says. “I tell my grandchildren and my son: ‘If you see what you can get out of [any] experience, it may come back later to be very useful.’”