Reading With Purpose

To navigate the expanse of information that’s now available to us, we must learn not only how to read deeply but when to read deeply.

Cultivating purposeful readers is perhaps more important than ever given today’s information landscape replete with fake news, “alternative facts,” misinformation and disinformation. To be informed citizens and participate in a democracy, we must first sift through all the information that bombards us regularly to determine what is important. Then, we need to be able to understand, assess, analyze and synthesize the most critical information.

There are real concerns about the next generation’s ability to do all of this: Headlines about students’ short attention spans and their reliance on skimming and scanning instead of deep reading appear regularly in the media. Research, including my own, supports this notion that skimming is students’ default reading practice. In 2022, researchers at

Eastern Kentucky University studied students’ perspectives on 20 critical reading behaviors that fall under the larger umbrellas of skimming, reviewing, synthesizing, questioning and applying. They found that while students consider more complex skills, such as applying, more useful than simpler skills, such as skimming, students still chose to skim more often when working on their assignments.

Technology is often blamed for students’ deteriorating reading skills, but it’s misguided

to think that there was some golden age in which most students were deep readers. In the 1980s, for example, researchers studied the reading practices of first-year college students, described as inexperienced readers, compared to graduate students, experienced readers. These first-year students were doing little more than skimming the surface of the sample texts they were given, whereas the experienced readers were reading more deeply and rhetorically. Deep reading, like any skill, becomes easier with instruction and repetition.

“Cultivating purposeful readers is perhaps more important than ever given today’s information landscape.”

Instead of harping on students’ deficits, we would be wise to admit that skim reading is a legitimate and useful reading practice. Certainly, it can be complemented by other reading practices (more on that below) and applied more strategically than most students do, but there is nothing inherently wrong with skimming. When I teach students how to locate relevant sources for their research projects, for example, I tell them that if they deeply read every source then they would never finish their projects. Instead, they must first skim the sources to determine their relevance. Deep reading is not always the best approach. Think for a moment about the reading that you do on any given day. Most of it is probably not what would be considered deep and sustained, yet it may, in fact, be very productive.

The problem, then, is not with skimming itself, but that students are not always purposeful readers. They don’t think about the context in which they are reading, why they are reading

or what they need to do with the reading. Professors must share with students why they assign reading in the first place and what students will be doing with the reading. Will students be expected to summarize, analyze, memorize, synthesize, imitate or offer a

personal response to the reading? To help students read purposefully, and therefore

better, professors need to address this question with each reading assignment. If students learn to read with purpose in their classes, they will be better readers after graduation whether they are reading for enjoyment or for information.

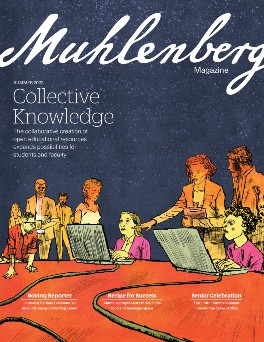

Reading with purpose helps students become more adept readers, as does marking up the texts they read. Annotations support deep reading practices by giving students the opportunity to engage directly with the text in its margins by raising questions, building upon an idea or challenging an argument, the very way they may need to mark up documents in professional settings after college. And this doesn’t only happen on paper — digital annotation programs allow students to mark up texts online and share their annotations with each other. In the digital margins of texts, students collaborate just as they may be expected to do with co-workers on professional communications after graduation. While technology may be to blame for the shift toward skimming, it also has the capacity to help students become more active, deeper readers.

Teaching students to read for credibility, bias and assumptions, often called critical reading practices, can support students’ active engagement with texts not only in their courses but in their personal lives — including on social media, where students get their news. Ultimately, though, students need to learn how to transition between these critical, deep reading practices and skimming. Empowering students to toggle between these approaches positions them to both navigate our vast contemporary information landscape and become informed citizens, which will serve them and our democracy for a lifetime.

Ellen C. Carillo ’00 is a professor of English and the writing coordinator at the University of Connecticut.