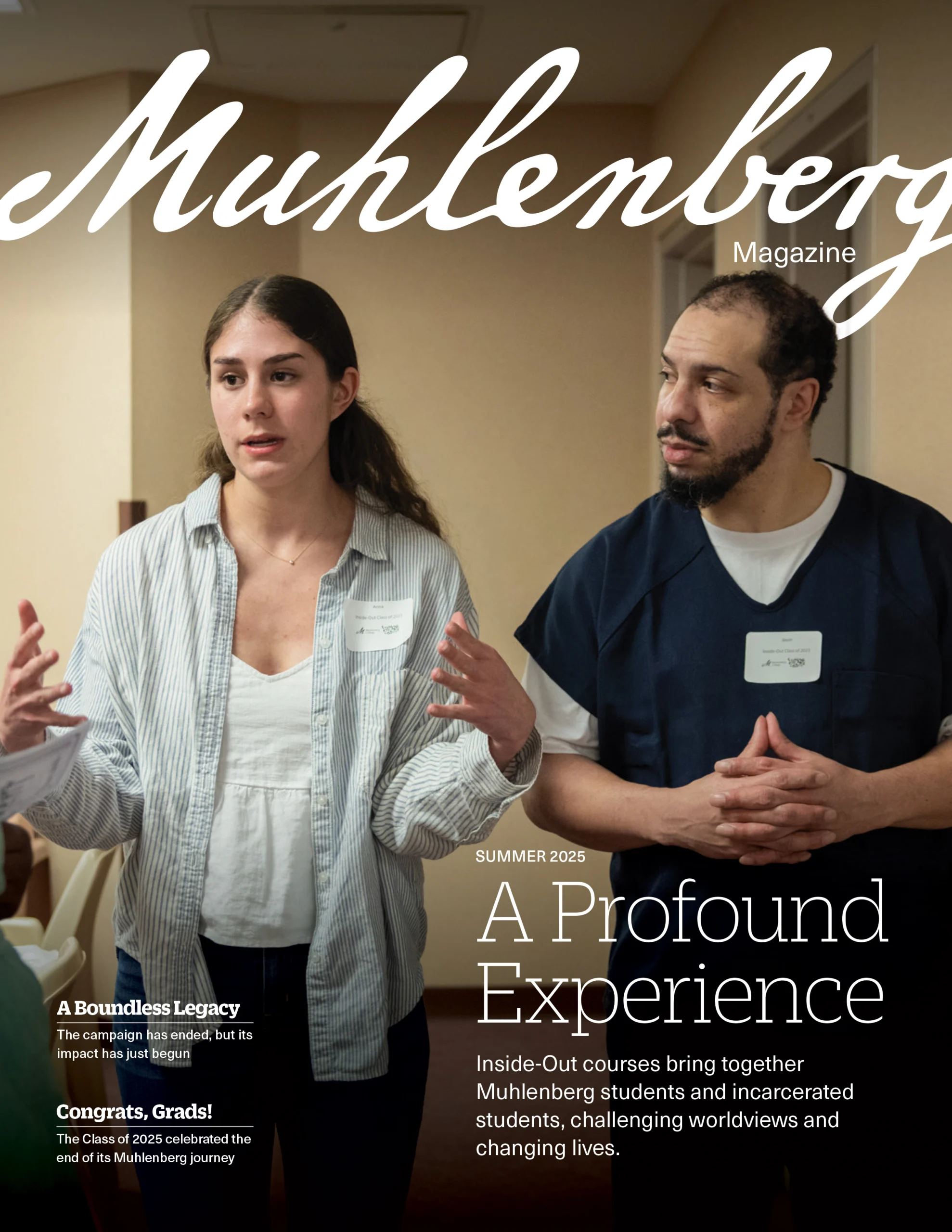

Why I Study Chronic Absenteeism From Elementary Schools

Professor of Psychology Stefanie Sinno explains how working with the Allentown School District led her to her current area of research.

Entering college, I knew I wanted to work with children. I joined a research project on the way kids worked with their friends because I liked the faculty member. I thought, “This gives me an ‘in’ to work with children and also to understand them.” I declared a psych major and took more developmental psychology classes. I loved research, being able to ask difficult questions and hear from kids themselves.

As a first-generation student, I had no intention to go to graduate school. My senior thesis advisor refused to advise me unless I applied. I ended up at the University of Maryland, where I worked for an after-school program. I researched what curriculum would have the biggest impact on the most kids. I discovered that psychology allows you not only to understand individuals, but also to research best practices.

I also started teaching in graduate school. It was the best of both worlds. You get to extend what you are learning through your research to your students so they can go out and use better practices with kids.

I came to Muhlenberg straight from grad school, and my goal was to work with schools. I prefer that the community tells me the questions that they have. I have the expertise, resources and time to answer those questions. Right now, what the Allentown School District (ASD) wants to understand is chronic absenteeism, or missing more than 18 days of school in a year.

“I prefer that the community tells me the questions that they have. I have the expertise, resources and time to answer those questions.”

—Professor of Psychology Stefanie Sinno

Coming out of the pandemic, I was at a luncheon with school principals and one said, “It’s been a struggle to get kids back into the classroom.” I offered to have my Advanced Research in Psychology class explore the problem. I think the principal was hoping the chronically absent kids would all be from one neighborhood, so they might be able to provide a bus and solve the issue, but the data showed that wasn’t the case. My students also started thinking about the variables that affect whether kids are able to come to school. At the elementary level, the parents and guardians are the ones getting kids there, particularly when, as in ASD, there is no busing.

Last fall, we deployed an absenteeism survey to five ASD elementary schools. Getting the information we need is really difficult. We need to reach the people who never show up in the school to ask them what factors keep them from getting their kid to school. My students and I will try outreach at jacket and meal giveaway days to say, “We’d love to talk to the district about more after-school programs, about safe travel to and from the school. They’re not going to listen without your voice.”

The goal of this survey is to learn how we can get more kids in the building. It’s a super complex issue. But the more you get kids motivated to be in school at the elementary level, the more likely they are to continue in school.