Make America Smoke Again

Public health efforts in the United States helped reduce cigarette use to historic lows. After cuts to key federal agencies, will our progress hold?

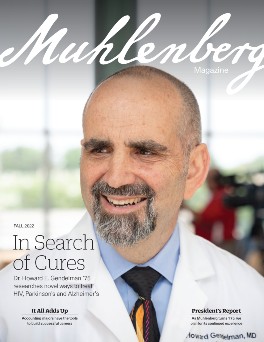

Americans are far less likely to smoke today than they were 60 years ago — the smoking rate among adults in the country fell from 42.6% in 1965 to 11.6% in 2022. This 73% reduction took place after then-U.S. Surgeon General Luther Terry released a 1964 report that found smoking raised the chances of developing lung cancer by up to 20 times and was also correlated with an increased risk for emphysema and coronary heart disease.

This report shook the country, and over time, we did a really good job of denormalizing smoking. Recent research from the American Cancer Society indicates that between 1970 and 2022, tobacco control efforts led to the prevention of 3.8 million lung cancer deaths, which equates to over 76 million years of life gained in the United States.

The changes happened incrementally and were driven locally and at the state level — for example, at one point in time, a waiter in California might have to inhale secondhand smoke as they served food, but in 1995, the state was the first to ban smoking in most workplaces. Also in the 1990s, dozens of state attorneys general brought lawsuits against the four largest tobacco companies that resulted in the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement, which raised the cost of cigarettes, prohibited advertising tobacco products to kids, and established the nonprofit Truth Initiative, the force behind the “You Don’t Always Die From Tobacco” PSAs that were ubiquitous on MTV and other youth-focused networks in the early aughts. I can still picture the 1,200 body bags they stacked outside the Philip Morris International (PMI) headquarters to signify the deaths caused by tobacco use each day.

“It’s not enough for countries to simply pass tobacco control policies — for policies to be effective, they also need to be successfully implemented and continually enforced. If they’re not, the tobacco industry stops their progress and rolls back everything these countries have done.”

I primarily work in low- and middle-income countries where the burden of tobacco is the greatest, places where the tobacco industry uses the playbook we saw play out in the U.S. Today, countries like Bangladesh, India, and Indonesia have tobacco use rates close to those in the U.S. at smoking’s peak. A lot of what we do at the Institute for Global Tobacco Control at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health aims to build capacity in these countries to do research and advocacy themselves. It’s not enough for countries to simply pass tobacco control policies — for policies to be effective, they also need to be successfully implemented and continually enforced. If they’re not, the tobacco industry stops their progress and rolls back everything these countries have done.

Which brings me back to the United States. We’ve seen how the tobacco industry has pivoted domestically since cigarette smoking became denormalized. E-cigarettes were introduced in the early 2000s and initially marketed as a healthier alternative to cigarettes for people already addicted. In 2017 and 2018, we saw the e-cigarette company Juul deploy youth marketing tactics, including advertising on the Nickelodeon and Cartoon Network websites and producing enticing flavors and product packaging, that drove an epidemic in youth vaping.

State attorneys general again filed suit, and the company now owes more than $1.1 billion in settlements for deceptive and misleading marketing practices, misrepresentations about nicotine content and product safety, and negligence in preventing underage sales both in stores and online. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has since prohibited manufacturers from marketing certain flavored tobacco products, and in April, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the ban. The number of young people who vape has decreased by a third since its peak in 2019.

The FDA’s Center for Tobacco Products is the office responsible for regulating the manufacturing, marketing, and distribution of these products. The Centers for Disease Control’s Office on Smoking and Health tracks tobacco use, provides funding for tobacco control programs, and promotes tobacco education and cessation programs. On April 1, news broke that many employees of the Center for Tobacco Products and all employees of the Office on Smoking and Health were fired in mass federal layoffs.

“Despite the denormalization of cigarette smoking in the U.S., the practice could make a comeback if the government starts to allow tobacco companies to push back against existing life-saving policies. However, I expect the industry’s focus will be on marketing heated tobacco products and e-cigarettes, which could, in turn, increase cigarette smoking as more people become addicted to nicotine.”

We know that these reductions in staff mean it will be harder to enforce existing public health policies and to implement new ones as the tobacco industry evolves, which it always does. Its latest evolution is toward “heated tobacco products,” which heat actual tobacco (instead of the liquids inside e-cigarettes) to create nicotine aerosols. Tobacco companies claim these products are safer than cigarettes, but the independent research conducted thus far does not support these claims.

These products were first introduced in the 1980s but didn’t catch on. In 2014, PMI introduced the heated tobacco device IQOS in Japan and Italy; after global success and a patent dispute during the first U.S. test launch, the product relaunched in limited markets in the U.S. earlier this year. At this point, the U.S. product is marketed toward existing users of nicotine products — as e-cigarettes initially were — and its flavor selection is limited. However, internationally, users can access a variety of fruity flavors and buy the devices in stylish shops reminiscent of an Apple Store. PMI, the largest public tobacco company in the world, seems to be all-in on heated tobacco products — and a less robust U.S. public health apparatus means more room for manufacturers to maneuver.

Despite the denormalization of cigarette smoking in the U.S., the practice could make a comeback if the government starts to allow tobacco companies to push back against existing life-saving policies. However, I expect the industry’s focus will be on marketing heated tobacco products and e-cigarettes, which could, in turn, increase cigarette smoking as more people become addicted to nicotine.

The tobacco industry, like all industries beholden to shareholders, puts profits over people every time. Public health is the invisible shield; preventative measures are often hard to see, but they are all around us. As reductions in federal resources weaken that invisible shield against the harms of tobacco products, the American public — especially the younger and most vulnerable people the tobacco industry typically targets — could see smoking rates rise and the accompanying diseases and early deaths return.

Kevin Welding ’03 is the associate director of the Institute for Global Tobacco Control at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. He holds a Ph.D. in economics from the University of California, Santa Barbara.