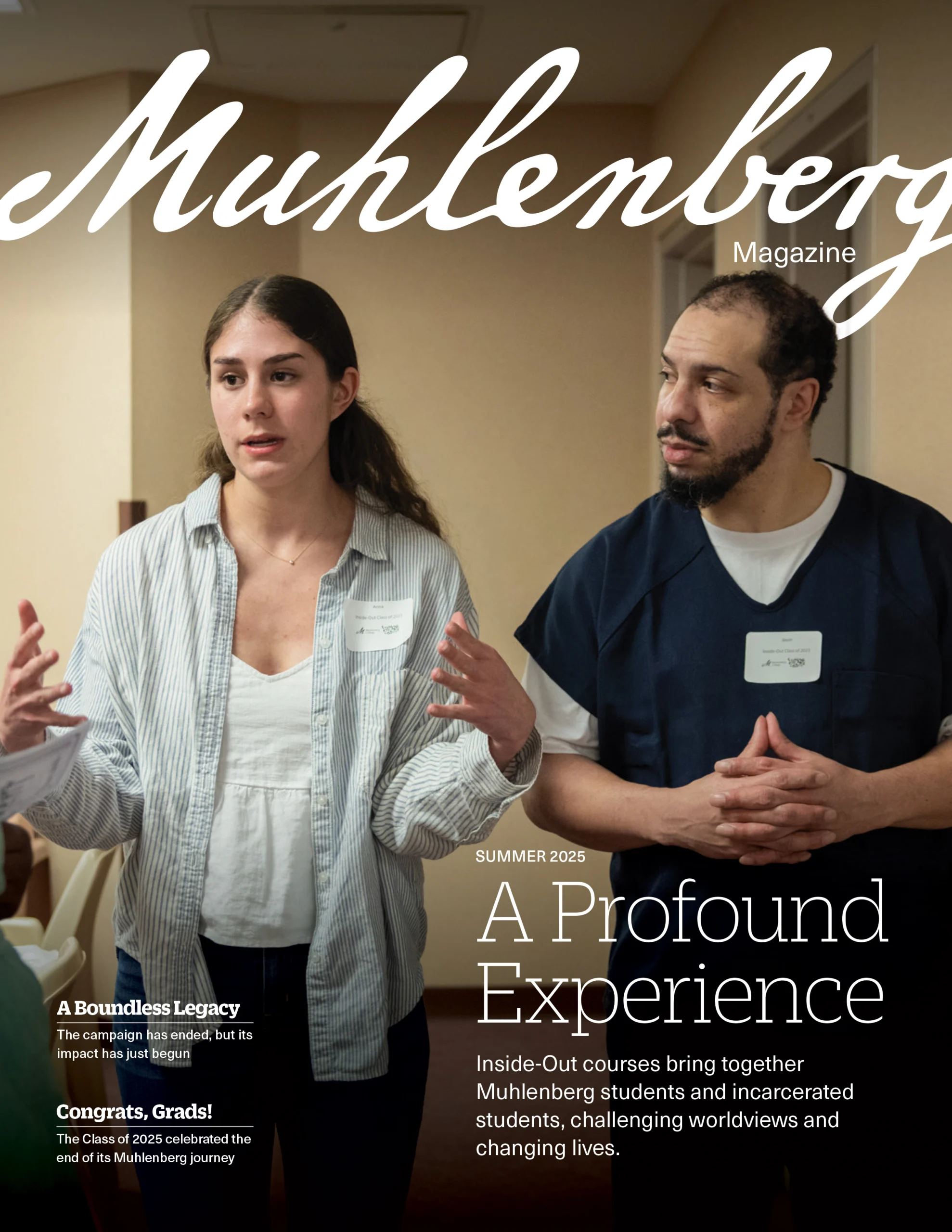

Richard Ben-Veniste Takes Our Questions

Ben-Veniste ’64, who served as one of the lead prosecutors during the Watergate scandal 50 years ago, reflects on the responsibilities of citizens in a democratic society, the challenges our country faces and what needs to happen to preserve our democracy.

Richard Ben-Veniste ’64 has had a front row seat to some of the most consequential moments in modern American history. As one of the lead prosecutors during the Watergate scandal, he was among the first to listen to the Oval Office recordings that would lead to the resignation of President Richard Nixon and criminal charges against several of his closest aides. “What we heard on that day was to change the course of American history,” Ben-Veniste wrote in his 2009 memoir The Emperor’s New Clothes: Exposing the Truth From Watergate to 9/11.

Ben-Veniste, who was a history major at Muhlenberg, also served on the 9/11 Commission, the bipartisan effort to determine how such a catastrophic act of terrorism occurred and how to prevent similar tragedies from happening in the future. It was in response to Ben-Veniste’s line of questioning that National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice revealed the title of the briefing President George W. Bush had received on August 6, 2001: “Bin Laden Determined to Attack Inside the United States.” Ben-Veniste publicly called on the administration to declassify the entire document and, two days later, under immense public pressure, it did.

Ben-Veniste, a trial attorney who also served as chief counsel for the Democrats on the Senate Whitewater Committee, opens his memoir by recalling an occasion when a conservative New York Times columnist accused him of being “too partisan” to serve as attorney general if presidential candidate John Kerry were elected. Ben-Veniste, who has prosecuted misdeeds on both sides of the political aisle, goes on to write, “Our democracy is dependent on hearing the truth from our elected leaders. Nothing less is acceptable. Policies built on a foundation of lies will in the end crumble. And where untruthfulness has fouled the halls of our American institutions, I believe that sunlight is the best disinfectant. As patriots who believe in our system of government, we should all be partisans … for the truth.”

Here, 50 years after the conclusion of his work on the case that launched his career, Ben-Veniste reflects on the responsibilities of citizens in a democratic society, the challenges our country faces and what needs to happen to preserve our democracy. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Muhlenberg Magazine How would you describe the relationship between democracy and truth?

Richard Ben-Veniste ’64 Our society is based on the rule of law, and the rule of law is based on certain truths that we hold sacred in this country. Unlike most other countries, the United States does not have a state religion. We pledge our allegiance to our republic and to adherence to our Constitution. And unless our citizens are committed to truth, there is no foundation for our government. Truth is the essential pillarby which everything else is supported in our society.

MM Right now, the American people don’t seem to have a shared understanding of what’s true and what isn’t. How has that affected our democracy?

RB We could go on a long time about how we got to this point — where individuals claim the freedom to decide their own truth. Our founders had a belief in human reason as a reliable basis for resolving common issues of governance and order. The notion that one may substitute opinion for objective truth or at least an intellectually vigorous system of determining what is true is antithetical to our democracy.

“The notion that one may substitute opinion for objective truth …

is antithetical to our democracy.”

MM How did we get here, and how can we find a shared understanding of the truth again?

RB The reason we got here has to do with many things that are inherently good about the evolution of our society. We have means of communication that surpass anything heretofore available on earth, but with that comes an obligation to be critical about how a responsible citizen forms the basis for actions that affect us all as a community.

What concerns me is the growing tendency to project opinion based on fallacies without regard to a shared concern for the common good. And with all the benefits available to us from the internet, it also provides a means for amplification of crazy conspiracy theories and a rallying vehicle for enemies of our democracy, both foreign and domestic.

For example, when I was a child, we had a polio epidemic, and Americans universally feared the polio virus. And until Dr. Jonas Salk and others were able scientifically to identify, isolate and then find a way to prevent polio, children were at risk of contracting a terrible disease. No one in their right mind would’ve said, “Oh, that’s a bad thing. We need polio just to run its course, and whoever gets paralyzed or worse just has to live with that.” And we were able to eliminate the scourge of polio in this country.

Finding the truth is a difficult business, and that’s the obligation of living in a democracy. If you want to live in a world where you’re just told what to believe, then you don’t live in a democracy. There seems to be a wholesale depreciation of the value of democracy in the public mind. People have to be educated into a belief that the protectionof democracy is the number one obligation of the citizenry. If you want to be a citizen in a democracy, you have responsibilities. And it’s the obligation of our educators to instill that in our children, that this is something they carry forward with them as citizens of a democracy. We have failed as a nation to adequately educate our children in basic civics.

MM What other role might education play in improving the state of our democracy?

RB The starting point is teaching critical analysis. It’s what we do every day: We make decisions based on our experience, our intelligence, our knowledge generally. We need to provide an appreciation for the value of decisions that are based on fact and objective truths. Perhaps that explains why I “borrowed” the title of my book from the great Hans Christian Andersen story of the simple truth seen through a child’s eyes when the adults in his kingdom were beguiled by a charlatan.

History is littered with examples of democracies that failed, and we must learn those hard historical lessons. It is the obligation on campuses such as Muhlenberg’s to weave civics education into the curriculum. A university cannot claim to be successful if it does not provide the basic education of how to live in a society that is based on the rule of law and our Constitution. Our founders were clear-eyed about the pitfalls of emerging would-be autocrats and deceivers who would substitute a cult of personality for democratic institutions.

MM How did your Muhlenberg education help equip you with the skills needed to be part of a democratic society?

RB Muhlenberg College was very helpful in providing a liberal arts education that rewarded critical thinking. I remember being in the audience and asking a question of our U.S. Senator Hugh Scott, who had a powerful leadership position in the Republican party at the time he spoke at Muhlenberg. I thought he was going to discuss serious issues of the day, but he just gave an anodyne campaign speech.

I asked him a question about something that I had been working on as a thesis for a history class — the 1954 overthrow of an elected president in Guatemala. I wanted his opinion, since he was an expert in foreign policy, as to whether the United States, contrary to official denials, played a role in the overthrow. He looked at me as though he’d been struck on the head with a mallet. Years later, the CIA eventually claimed responsibility for overthrowing the president of Guatemala, but Hugh Scott didn’t expect the question to come from a college audience, especially at a college that was known for its docile demeanor at the time.

And yet Muhlenberg gave me that opportunity, and I wasn’t told to hush up or “be respectful to my elders.” My professors encouraged me to speak out, and if I was on the wrong track, someone would show me facts to set me straight. I credit that liberal arts education with providing the fundamental framework for graduates to adopt a sensibility of critical thinking as they approach life, and that has stood me in very good stead.

MM What are the biggest challenges our democracy faces at the moment?

RB In the short term, it looks pretty grim, because there’s a lot of stupid going on and a great deal of dysfunction in government. But, if you look back in history, our nation has overcome events that were much more consequential than what we face now. George Washington faced the most powerful military force in the world, and we prevailed.

Abraham Lincoln faced a Civil War that was so ruinous, so horrific, so barbaric, and yet our union was able to prevail and go forward, although the scars still exist. Franklin Roosevelt faced a horrendous situation economically and then militarily and was able not only to lead the United States through but prevail and establish the United States as the democratic force to be reckoned with in the world.

What we face now is an assault on rational thinking, on objective truth and on decision-making based on the common good for the country. We have reason to be hopeful in the long run looking at our history, but that doesn’t minimize the threat that presently exists. The observation, often attributed to Thomas Jefferson, “the price of democracy is eternal vigilance,” has provided a guiding beacon for me over a long period of public service.

Take the 9/11 Commission, which I think is a hallmark of bipartisanship. People were committed to a central goal — bettering our society, preserving our democracy and finding answers to questions that were difficult to answer — and to finding a way forward that people could agree on. We showed that it could be done if people put aside their partisan impulses to work toward a common goal. We were able to produce a factual record upon which we made recommendations that were enacted almost 100% by the U.S. Congress into law, and we have made ourselves safer against foreign terrorist attacks.

We should have had such a commission to look into the response to COVID, yet we could not agree on setting up a commission to better prepare us for the next virus that will attack us. To provide for the common good, such a commission would have been very helpful. If we don’t learn from the past, we are destined to repeat it.

MM What changed to make such a commission on the COVID response impossible?

RB I think there are a number of things. One is the internet and the ability of people to express opinions that are untested, unverified and unmoored by critical analysis and project those opinions in place of news or truth to a large number of people who are susceptible to being hoodwinked. A common threat became a partisan issue to be exploited.

Another part is the notion of a professional class of politicians. The founders of our country didn’t look at political office as a sinecure or an occupation. They looked at it as a temporary obligation of citizens to serve. Now, the most important part of being an elected official for many, many office holders is to be reelected and to enjoy the perquisites of public office rather than to serve the public. Elected officials 50 years ago used to socialize with one another, no matter their party, because they understood that they were fundamentally kindred spirits. They were Americans, they were patriots and they were committed to democracy. In present-day Washington, members of Congress spend most of their time siloed in their offices before racing home at every opportunity to raise money so that they can be reelected.

That points to another ingredient undermining our democratic institutions: the emphasis on money in politics. Attempts to curb it have not been successful, resulting in a great disservice to our country. Other countries have democracies without the absurd amount of money that’s poured into our campaigns. It’s a quid pro quo, a legalized form of bribery. Our system cannot exist as a legitimate and honest form of government with that kind of use of money, a fundamentally undemocratic development of much more recent vintage in the history of this country.

“We face a fearsome and

multi-dimensional threat matrix,

but we’ve proved over time that we’re capable of defending our democracy.”

MM What dynamics are you watching most closely in this presidential election year?

RB I’m retired from my law firm and I’ve donated my papers to the University of Texas Briscoe Center for American History, so I’m just another guy watching events and trying to maintain a sense of humor. Whether the electorate will embrace a presidential contender, now a convicted felon, who does not respect the norms of government, has urged mob violence and will not pledge to abide the result of the next election if he loses again,

remains to be seen.

I’m hopeful. I see a glimmer of the kind of activism that should be present on campuses, with people with strongly held opinions voicing them, who should be allowed to voice them (albeit without the violence that sometimes attaches to it). It might not be in the direction that I would choose to prioritize, but I’m hopeful. What’s changed in my lifetime is that we now have a professional army rather than a draft army; the draft was responsible for shortening of the Vietnam War, although it dragged on far longer than it should have. Students who had a substantial stake at a young age in the direction of our military and foreign policy had loud voices. Until recently, campuses have been quiet as our democracy has been challenged by enemies foreign and domestic.

We face a fearsome and multi-dimensional threat matrix, but we’ve proved over time that we’re capable of defending our democracy. It only remains to be seen whether we as citizens have the commitment and good sense to preserve the republic entrusted to us by the likes of Franklin, Washington, Jefferson and Madison.