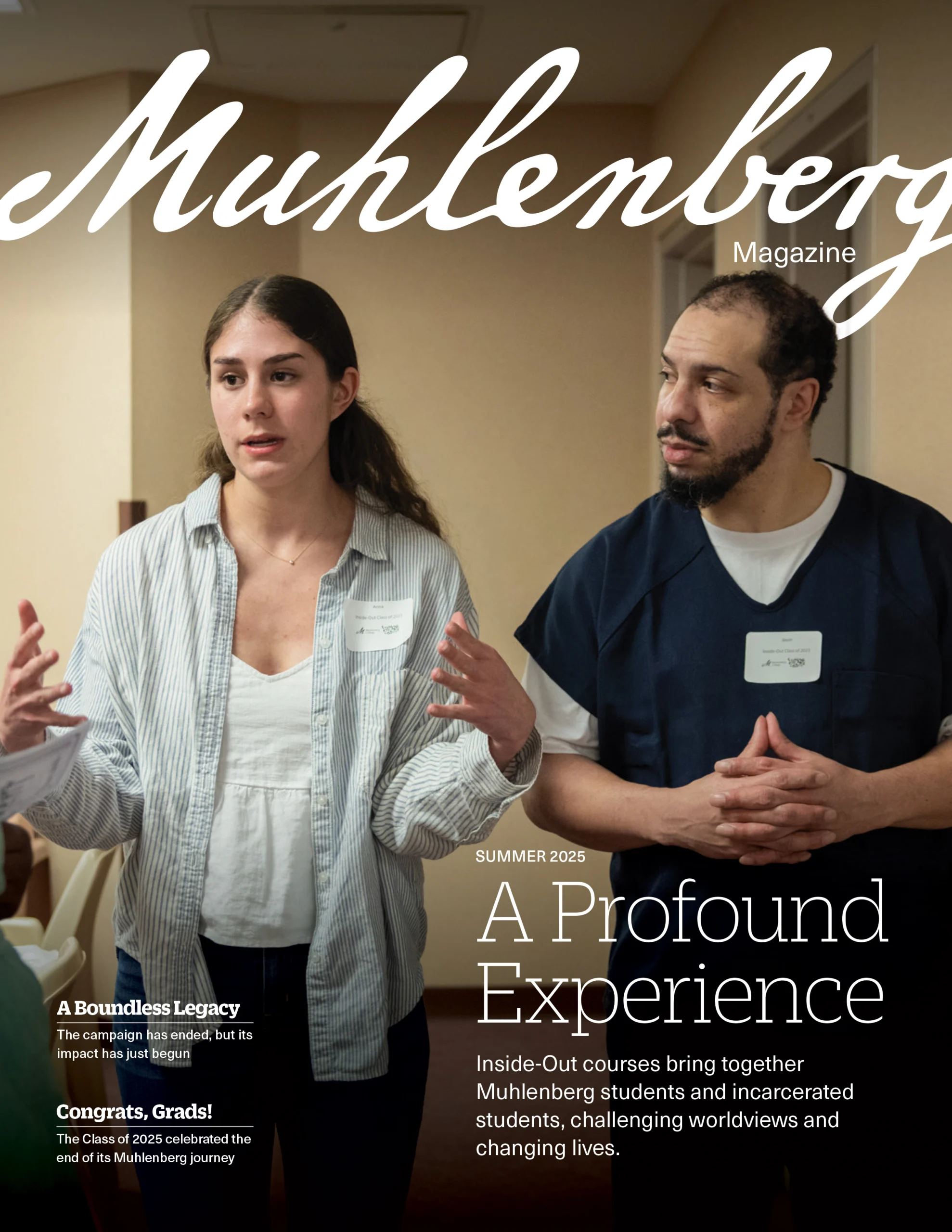

Hacker Hunter

Cybersecurity expert Priscilla Moriuchi ’03 spent 13 years with the National Security Agency before entering the private sector. Today, in addition to her product security role with Apple, she studies and speaks about the cyberthreats posed by nations like North Korea, China and Russia.

Photos by Matthew Guillory

Early this year, hackers compromised tens of thousands of American organizations—health care providers, law offices, universities, think tanks, manufacturers and a variety of others—by exploiting a weakness in Microsoft email server software. The hackers used a technique that allowed them continued access even after an organization installed the patch Microsoft provided. The American victims made up a fraction of the hundreds of thousands of organizations estimated to have been affected by the hack globally.

In July, the United States and its allies blamed China for the Microsoft attack. At the same time, the Justice Department indicted four Chinese citizens accused of working with Chinese intelligence agencies to steal intellectual property, including trade secrets and medical research, from American entities.

“For intelligence services, going after governments is expected. We don’t enjoy it when we’re the ones that get attacked, but we understand that we also engage in cyberoperations and are looking for classified information from our adversaries and that’s part of the playing field,” says Priscilla Moriuchi ’03, a senior security researcher at Apple and non-resident fellow at Harvard University’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. “We’re unique in drawing the line at using government resources to steal information from private companies to then prop up and give a competitive advantage to your own domestic companies. It’s a uniquely American position, one that is taking us decades to educate the rest of the world about, that this behavior should be unacceptable.”

Almost every time a cyberattack makes headlines, you can find a news outlet quoting Moriuchi. Before she moved to Apple last June, she spent three years as director of strategic threat development at Recorded Future, a cybersecurity company based in Boston. Prior to that, she worked at the National Security Agency (NSA) for 13 years. By the time she left, she was the NSA’s chief analyst for Asia and Pacific cyberthreats, including those coming out of China, Russia and North Korea.

“Promotion within that agency to a position as senior as Priscilla obtained reflects the consummate level of her analytic and bureaucratic skills and an ability to communicate vital findings clearly and concisely not just to fellow experts but also to an audience of generalized policymakers,” says Chris Herrick, retired professor of political science. “In her senior year, she was recipient of the James W. and Barbara H. Herrick Award, given to the graduating international studies major who showed the most promise for a career in international relations/studies. In her subsequent career, she has certainly demonstrated that she deserved that award.”

Inside the Intelligence Community

A class with Herrick is what inspired Moriuchi to study abroad in China, an experience she describes as “life-changing.” She entered Muhlenberg intending to declare a biology major en route to a career as a genetic counselor, a profession that had intrigued her since middle school. However, the chemistry courses she took as a first-year student were a wake-up call: “I realized the fundamental, basic science that underpinned that career wasn’t something I was interested in,” she says. “It kind of took me off my path.”

As she started taking political science and language courses, she found a path again. She discovered in herself a curiosity about the world and a desire to travel. She’d grown up in Lewiston, Maine, and had rarely left the state; she’d flown only once, to Walt Disney World, before she departed for China in the fall of her junior year. She studied in Dalian, a small city in northeast China, and was one of a small handful of Americans in her school. Her friends were from places like South Korea and Japan.

“I started learning about these histories and dynamics in Eastern Asia that I’d never learned about, and the impact those histories and cultures have on the world,” she says. “I was studying in China when they were opening up and their economic growth really started to kick in. I spent a lot of time studying the language, trying to meet Chinese people and understand their system of government and how they placed themselves in the world and thought about their futures.”

When she returned to the United States, she continued to hone her language skills and learn more about China and its neighbors. She applied and was accepted to a program that would have her teach English in a remote part of China for a year or two after graduation. But by the time she graduated in the spring of 2003, with an international studies degree and a minor in Asian traditions, she was jobless: The SARS outbreak had forced her program and others like it to cancel. She took a position as a tennis counselor at a sleepaway camp as she pondered what to do next.

“I did not have a cell phone—I just wasn’t into being reached all the time,” Moriuchi remembers. “I got this call over the camp PA system: ‘Counselor Priscilla, your mother is trying to reach you.’ When I called her back, she said, ‘Somebody from the NSA has been calling the house. I don’t know what to tell them. Did you do something?’”

It turned out to be a recruiter. Moriuchi had attended a job fair during her senior year at Muhlenberg, and the recruiter noticed the Chinese language background on her resume. The NSA thought Moriuchi would be a good fit for its Intelligence Analyst Development Program, a three-year rotational program for recent graduates. She underwent the extensive process required to obtain a security clearance and started with the NSA the following summer.

Over the next three years, she rotated through NSA offices specializing in East Asia while attending grad school at George Washington University at night. By 2007, she had a master’s degree in international relations and affairs and a full-time role in a counterintelligence office at the NSA.

An Unexpected Journey

Moriuchi’s first job involved researching other countries’ intelligence services (mostly those of China and Russia, at the time) and determining how they were trying to gain access to American classified data. The intelligence community was only beginning to realize the magnitude of the threat of cyberoperations, Moriuchi says.

“We were just learning about how interconnected companies and governments really are. We were learning about vulnerabilities, in software and hardware, and really forming the base of the cybersecurity and information security industry as we know it,” she says. “It was exciting to have been there during that time, at the foundation for a lot of the cybersecurity community.”

Unlike many of her colleagues, who were trained in computer science, Moriuchi approached cyberthreats and cyberoperations from a geopolitical standpoint. She had learned enough through the rotational program and additional NSA training to understand the technical side of cybersecurity, but she brought to the table extensive knowledge of the context in which adversarial nation-states were carrying out their operations.

This expertise helped Moriuchi advance within the agency, and by 2015, she was the chief analyst for all Asia and Pacific cyberthreats. She set the mission and priorities for a team of more than 200 people. She played a pivotal role after the U.S.-China Cyber Agreement—“the only bilateral agreement countries have signed that’s supposed to put some boundaries around cyberoperations,” per Moriuchi—was established in 2015.

“I was in charge of making sure China was following its obligations. It was not supposed to utilize government resources to conduct cyberoperations for economic gain, to give Chinese companies a competitive advantage,” she says. “Ultimately, there was no enforcement mechanism for that agreement.”

The question of how to impose consequences for cyberoperations is one the U.S. still struggles with, in part because the scale of the damage often isn’t quantifiable until years down the road. Moriuchi gives the example of the wind-power industry: Ten or 15 years ago, it was dominated by American companies. Now, because of long-ago cyberoperations that stole intellectual property, it’s dominated by Chinese companies.

The United States has started indicting the foreign government officers responsible for cyberattacks, as it did with the four Chinese operatives named in July. The FBI realizes the subjects of these types of indictments are unlikely to see the inside of an American courtroom, but the practice is still useful: It demonstrates where the U.S. draws the line on cyberoperations and helps disseminate information companies can use to protect themselves.

“Small to medium-sized companies don’t have teams of information security professionals. In pharmaceuticals or the biomedical industry, a lot of companies are small, with cool, innovative ideas that could be groundbreaking years from now,” Moriuchi says. “It’s about getting information out to the one defender that works at that pharma or biotech company: ‘Here’s the threat. Here are defensive measures you can take to help yourself defend against a nation-state coming after you.’”

Life After Government

Moriuchi continued to generate and distribute such information even after she moved to the private sector in 2017. The hours she worked at the NSA—sometimes leaving the house at 5 a.m. and not returning until 7 or 8 p.m.—did not leave much time for her to spend with her new daughter, and she sought greater flexibility. She relocated to the Boston area to become the director of strategic threat development at the cybersecurity company Recorded Future. There, she conducted and published research on the operations of nations like China, Russia and North Korea using publicly available information.

“The role was pretty similar, even though I wasn’t working in government. Private industry and researchers are, in many ways, the unclassified intelligence that helps governments on the public side,” she says. “It allowed me for the first time to talk to people about intelligence work, which I’d never been able to do in the past.”

In 2019, while still with Recorded Future, she joined Harvard as a non-resident fellow. The position allows her to collaborate with other experts as well as undergraduate and graduate students on research. Her fellowship is with the Korea Project, whose goal is “to foster a deeper understanding of rapidly evolving security challenges on the Korean Peninsula and to develop creative approaches to effectively address them,” according to its website.

Moriuchi contributes to the project with research on North Korea’s unique style of cyberoperations: “Most countries use their military and intelligence services to conduct operations against companies or governments, looking for information. North Korea is focused on stealing and generating revenue,” she says. “The Kim family essentially runs a cybercriminal organization. They use the state to conduct these operations where they’re doing things like stealing millions of dollars from banks or ripping people off on online gambling sites. They’re so outside the nation-state norm.”

These kinds of operations can generate upwards of hundreds of millions of dollars, which could support something like a nuclear weapons program. Still, Moriuchi says that the intelligence community was not focused on this type of revenue-generating activity when she left in 2017. Today, her work with the Korea Project helps sound the alarm.

“I try to produce research and find new ways North Korea is generating revenue. I try really hard to engage with governments and other researchers to study this and to pay attention, both as a problem but also as a model,” she says. “Other rogue nations, there’s nothing to stop them from emulating this model. We have already sanctioned North Korea to the most extreme extent, and it’s not really helping to solve this particular cyber problem.”

Last year, Moriuchi switched gears professionally and went to work for Apple in a more technical role than she’d previously held. There, she’s a senior security researcher responsible for product security—that is, helping to protect anyone who uses an iPhone or a Mac. It’s a shift in that, for the first time, she’s not just identifying and publicizing potential threats. She’s able to actually implement changes to improve the security of Apple devices.

“I really enjoy protecting normal people,” she says. “I spent so much of my life focused on military and government networks, which are really a small slice of the world. Today, I feel gratified that the things I do are helping to protect normal people against threats they could never be equipped to handle. An individual cannot protect themselves against the North Korean intelligence services. I’m having a positive impact in helping people behind the scenes.”