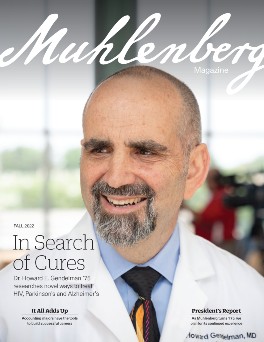

George Wheeler ’72

Wheeler worked at the Met as a scientist in its Department of Objects Conservation before serving as director of conservation for the Historic Preservation Program at Columbia University.

In the late 1400s, Italian sculptor Tullio Lombardo created “Adam,” a life-sized, 770-pound marble statue of one of the stars of the Book of Genesis. In 2002, the platform on which “Adam” stood buckled. “Adam” fell to the floor and broke into 28 large pieces (and hundreds of smaller ones). Conservators at The Metropolitan Museum of Art cordoned off the area and mapped the locations of all the fragments.

At the time, George Wheeler ’72 worked at the Met as a scientist in its Department of Objects Conservation. Wheeler would go on to lead the research on what materials should be used to reassemble “Adam.”

“We generated some brand-new science in the process of studying how to put this thing back together,” says Wheeler, who was an art history major with minors in physics and mathematics at Muhlenberg. “Historically, we would use big, stainless steel pins [to attach the larger pieces] and glue it back together with epoxy. We were saying, ‘Do we really need to do that?’”

Wheeler’s team researched reversible adhesives, ones that could be dissolved if something better comes along in the future, as well as the viability of smaller, fiberglass pins. Both technologies were ultimately used in the sculpture’s restoration, which was completed in 2014. “Adam” is one of many high-profile projects he’s worked on; he has also been involved in the preservation and/or restoration of Auschwitz, the Alamo and the sculptures of American artist Jeff Koons, whose work has set auction-price records for work by a living creator.

“[Art] influences the people around you into being receptive to different ways of thinking, different ways of doing things. That’s what the liberal arts does.”

Wheeler, who has master’s degrees in art history, art conservation and chemistry as well as a Ph.D. in chemistry, worked at the Met for 25 years. Throughout that time, he also taught in the Conservation Center of the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University, his art conservation alma mater. He left the Met for a full-time faculty role, serving as director of conservation for the Historic Preservation Program at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture Planning & Preservation from 2004 until 2017. He retired completely from teaching in December 2021.

“I’m more of an introvert than an extrovert, but that all seems to drop away when I’m teaching,” says Wheeler, who continues to do consulting work on the conservation of sculpture and architecture. “One of the things I do well is I teach scientific and mathematical concepts to students who are not necessarily strong in that area.”

He excelled at math and science from the start at Muhlenberg — he recalls helping classmates who were taking physics to fulfill a premed requirement — but what he discovered as an undergrad was the power of art. One of his sophomore year roommates, Steve Martin ’72, suggested they take an art history course on French painting together.

“It opened up a new world,” Wheeler says. “It’s not just [art’s] beauty, but also, it challenges you … New thoughts, new ideas come from having your foundations disturbed a little bit, and that’s one of the things that art does.”

The exposure Muhlenberg provided to both the arts and the sciences set Wheeler up for success in the world of art and architecture conservation, which requires both types of expertise. He also benefited more indirectly, from being at an institution with a commitment to exploration and well-roundedness.

“I think about the arts as disruptive to mental processes in a really good way. It makes you think differently, and that’s what happened to me at Muhlenberg,” Wheeler says. “It influences the people around you into being receptive to different ways of thinking, different ways of doing things. That’s what the liberal arts does.”