Behind the Music

Award-winning rock journalist David Fricke ’73 reflects on the journey that took him from WMUH to SiriusXM, including the more than 40 years he spent writing for Rolling Stone.

Photo by Claire Vogel

Weeks before entering Muhlenberg as a first-year student, David Fricke ’73 subsisted on hot dogs and spaghetti as he camped with friends in Bethel, New York. The town ballooned to more than 100 times its usual occupancy when Fricke and 400,000 others descended upon it for what the event poster called An Aquarian Exposition, drawn by the promise of “3 Days of Peace & Music.” You may know the exposition as Woodstock.

“You could experience the music through records, the radio, what I was reading in underground newspapers and the first few issues I was getting of Rolling Stone, but to encounter that many like-minded people in a peaceful circumstance that was constantly on the edge of disaster, you saw the kind of binding agent that music could be,” Fricke says. “We pulled it off, and we pulled it off in peace, and we took that lesson back to our communities.”

The experience set the tone for Fricke’s time at the College, where he studied English and added an unofficial “major” in WMUH. He started at the radio station in his first semester and took on leadership roles, as music director and program director, as an upperclassman. The subscriptions arriving in his residence hall mailbox, including Rolling Stone and the British weekly Melody Maker, helped inform which albums he would solicit from record companies, play on the air and review in The Muhlenberg Weekly.

“If I had a waking moment that did not involve schoolwork, I was [at the station] doing shows, doing substitute shifts,” he says. “I took the shifts that nobody wanted: midnight to 3 a.m. on Friday nights, Sunday mornings 9 a.m. to noon. Nobody wanted those. So I took them and did what I thought was good, progressive underground radio.”

By the time Fricke graduated and moved back to his native Philadelphia, he knew he wanted to interview musicians and write about music for a living. He also knew he had a lot of on-the-job learning to do before he could turn that passion into a career. Fricke first subsisted on earnings from a day job at an Army-Navy Store while writing for underground music papers and hosting an hour-long show on Saturdays at midnight for a local public radio affiliate. He went on to dabble in concert promoting and publicist gigs, all while continuing to write. His first freelance piece appeared in Rolling Stone in the fall of 1977; the following year, he moved to New York City, where he’s lived ever since.

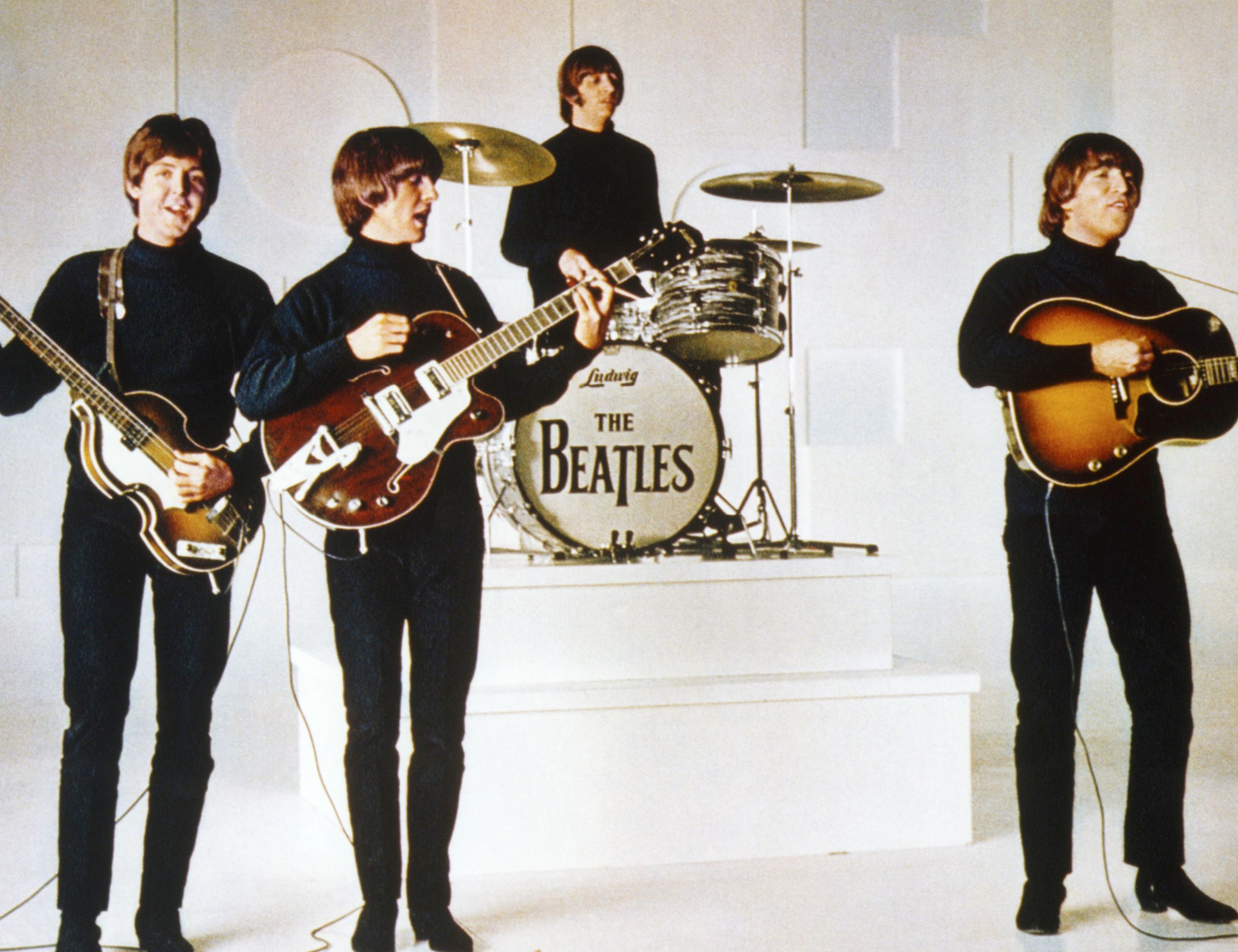

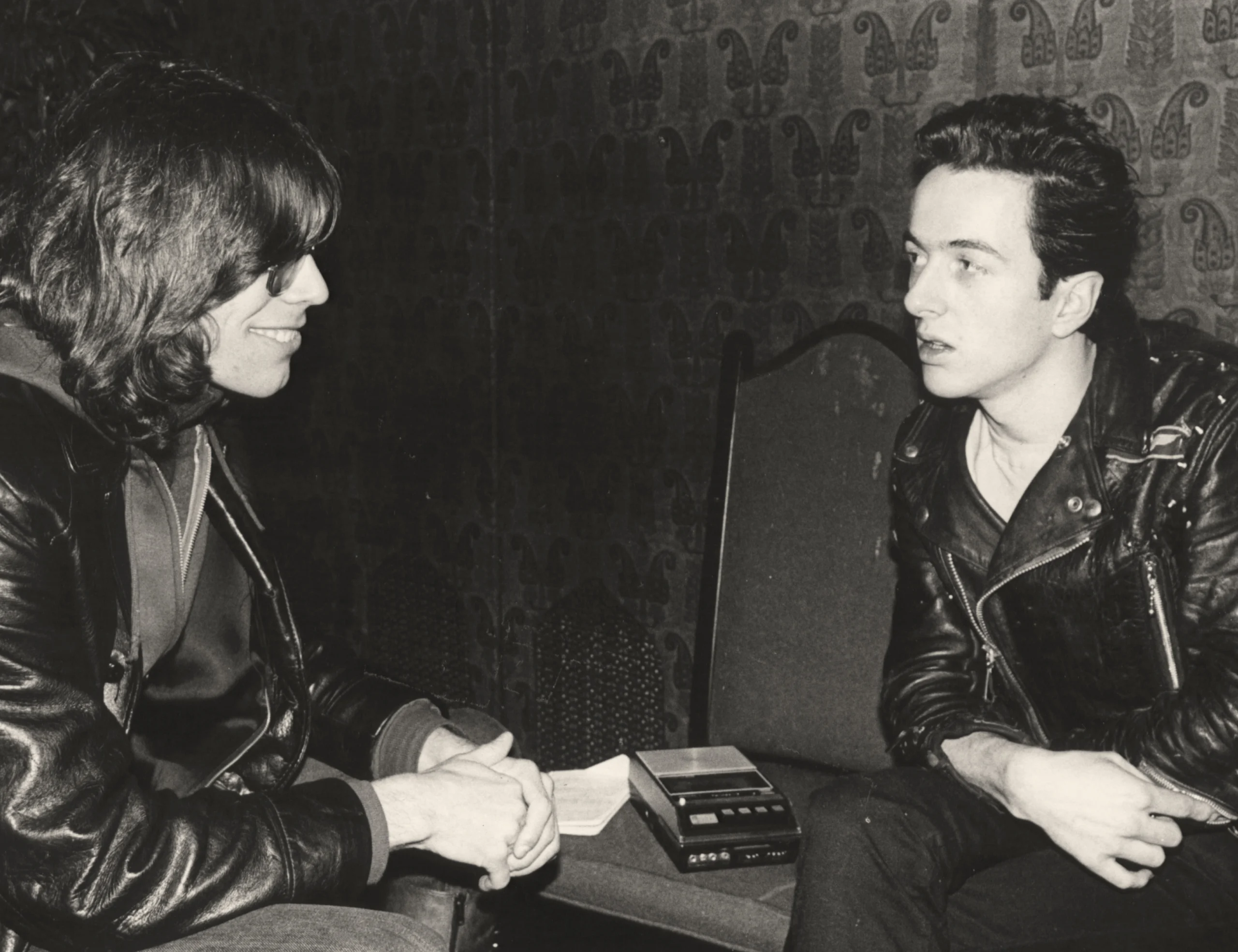

Staff writing and editing jobs at the now-defunct music publications Circus, Musician

and Star Hits led to his working as a staff writer for Rolling Stone for more than 30 years. He’s interviewed many artists multiple times over the course of his career, among them members of Led Zeppelin and The Rolling Stones, plus Paul McCartney and Lou Reed. Fricke built relationships with these musicians and others by bringing a genuine curiosity about music and the people who make it to every interview.

“I’m not going in there just to get stuff from people. I’m there to do a job, definitely, but I’m also there to have an interaction that hopefully will have a benefit on both sides,” he says. “I want the other person to feel good about it. They may drop a little guard and actually say things that are actually a little closer to home than they might if they thought they were talking to somebody with a certain agenda. You’re there to find out what’s going to happen, not make something specific happen.”

Today, in addition to freelancing for the U.K. music magazine Mojo (for which he’s written since 1993) and writing album liner notes, he hosts at least two weekly shows on SiriusXM. For Sirius, he’s interviewed musicians like Keith Richards of The Rolling Stones, Wayne Coyne of The Flaming Lips and Dan Auerbach of The Black Keys.

“It is full circle. I started out wanting to be in radio. I’m at a point where I can bring everything I did as a writer, interview-wise, and my music knowledge, to the radio twice a week if not more,” Fricke says. “It’s journalism on the air.”

Now, decades into his career, Fricke reflects on some of the most memorable moments, relationships and lessons of his life as a music journalist and fan in a conversation with Muhlenberg Magazine.

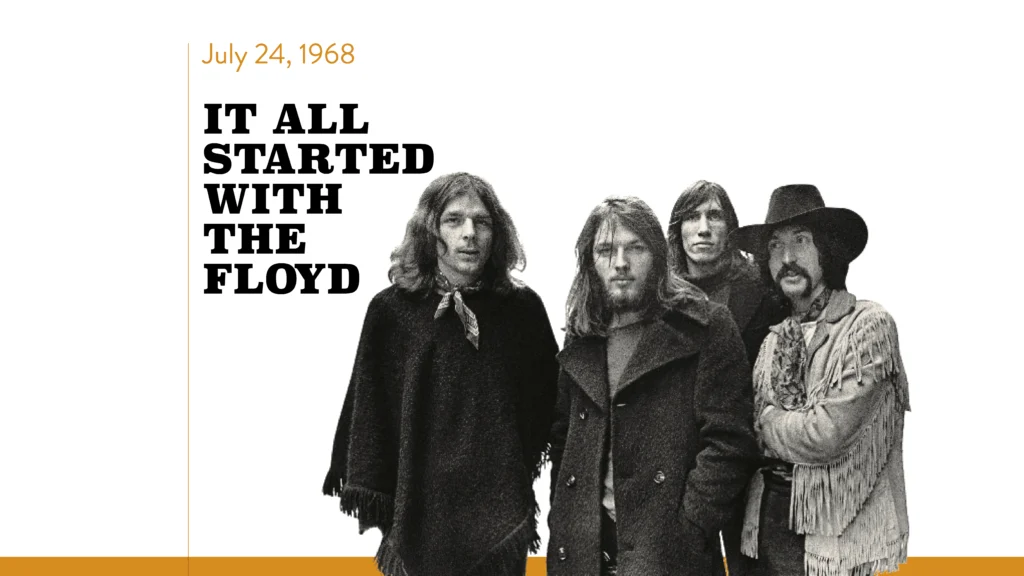

The English Invasion tour brought The Who, Pink Floyd and three other bands to Philadelphia’s John F. Kennedy Stadium, an outdoor venue that stood where the Wells Fargo Center stands today. Fricke, a rising high school senior, had a growing record collection, but he had never seen a live show. Almost 20 years later, Fricke interviewed Pink Floyd’s former bassist Roger Waters and its then-guitarist David Gilmour as Waters sued his ex-bandmates over use of the Pink Floyd name. The nearly 6,000-word cover story for the November 19, 1987, issue of Rolling Stone illuminated the infighting that destroyed one of Fricke’s formative bands.

It was a dollar to get in [to the show]. I knew about the Floyd and had heard them on the radio, but the band at the top was The Who, and I was hoping to see them. A friend was going to go with me, but he bailed at the last minute. To his eternal credit, my dad went. He rode the subway with me and agreed to sit three rows away so I didn’t look like I was there with my dad.

There was a thunderstorm that rolled in and The Who never got to play, but the Floyd were brilliant. Seeing any live music for the first time, it just opens your consciousness. Being in an enormous outdoor venue with a few tens of thousands of other people, there’s a sense of community. Even though I didn’t know anybody there—except my dad—we were all sharing the same thing. And even the fact that the show got blown out, we shared that, too. As far as I was concerned, I knew what I was going to do for the rest of my life.

[For the 1987 cover story], meeting those musicians for the first time, it was very important for me to establish as much of a relationship as I could, because I was there to do a job: to find and bring back insight and information that the folks out in the cheap seats didn’t get to have a piece of. And, to try to figure out how to tell a story in which there were two very, very polarized points of view.

As someone who knew [Pink Floyd’s] music and the genesis of it and how they created a lot of it, I could speak to both sides. I wasn’t there to pass judgment. I was there to report and to describe, and to bring back as comprehensive a portrait as I could in the time and space I had. That’s what journalism is.

I succeeded, because I had ongoing relationships with [Waters and Gilmour] going forward [from that first interview]. I did my research and I went in both as a professional and as someone who had an affinity for what they did—for their music, for their own artistic viewpoints and pursuits. That was something that I tried to do in every instance, whether I was talking to a young band just starting out or I was talking to somebody like the Floyd.”

The first half of the 1980s saw the rise of MTV (which, at the time, stood for Music Television) and the launch of a significant ad campaign to distance Rolling Stone from its hippie roots and embrace more of the pop-culture mainstream. While Fricke’s first freelance piece for Rolling Stone was published in the fall of 1977, it took until April 1985 for him to land one of the staff writing jobs there, which he describes as “few and far between” at the time. In the interim, he worked for several other music publications and made valuable connections, including a friendship with former MTV News correspondent and current SiriusXM host Kurt Loder that continues to this day.

To be published [in Rolling Stone] was a big deal. If I hadn’t written for them, I probably would have been disappointed, but in all the time before I got there, it’s not like I was sitting around moaning and groaning. I was going to gigs. I was writing for Melody Maker. I had the ability to hang out in New York at CBGB or go to The Bottom Line. I was making my first road trips. I didn’t have anything to complain about.

[Kurt Loder] and I met at the end of ’77 because I came to New York to interview for a job at this free weekly paper called Good Times that he was working at. He actually ended up living across the street from me—the apartment complex we lived in was public housing, and he helped me get through the application system because I wasn’t a resident. We were palling around, going into the city, going to clubs.

Many of us [music journalists] from that period of time, we were advocates for the music that we loved, for writing, for passionate journalism. It was a small circle because, frankly, there was no money in it. So you did it because you loved it and you liked being around other people who did it.

[Kurt and I] both ended up at Circus at the same time [in 1978] before he left for Rolling Stone. He took a sabbatical to work on Tina Turner’s book, I, Tina, as coauthor. I ended up working at Rolling Stone as a temp because they needed someone to fill in while he was on sabbatical, and I just never left. They asked me to stay, and I did. Not long after that, [Kurt] went over to MTV to work as a journalist and anchor there for many years, but we’ve been thick as thieves ever since.

Writing for Rolling Stone was about getting close to an ideal. It wasn’t the only place to be, but it represented a certain quality and authority in the work that I did and had the opportunity to do that was really, really precious. Once I got there, I realized that I was there to live up to those standards and hopefully to enhance them by doing better work.”

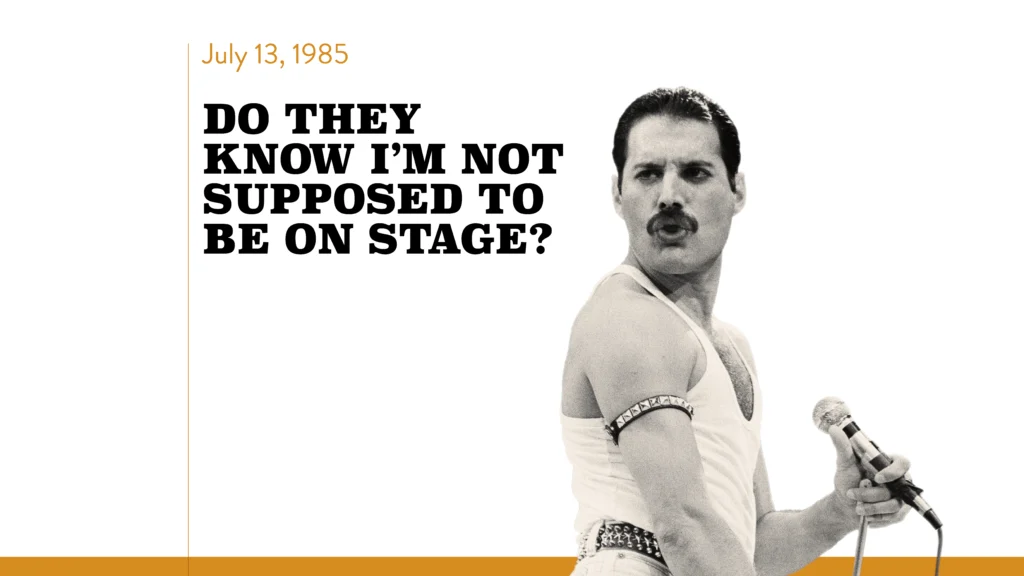

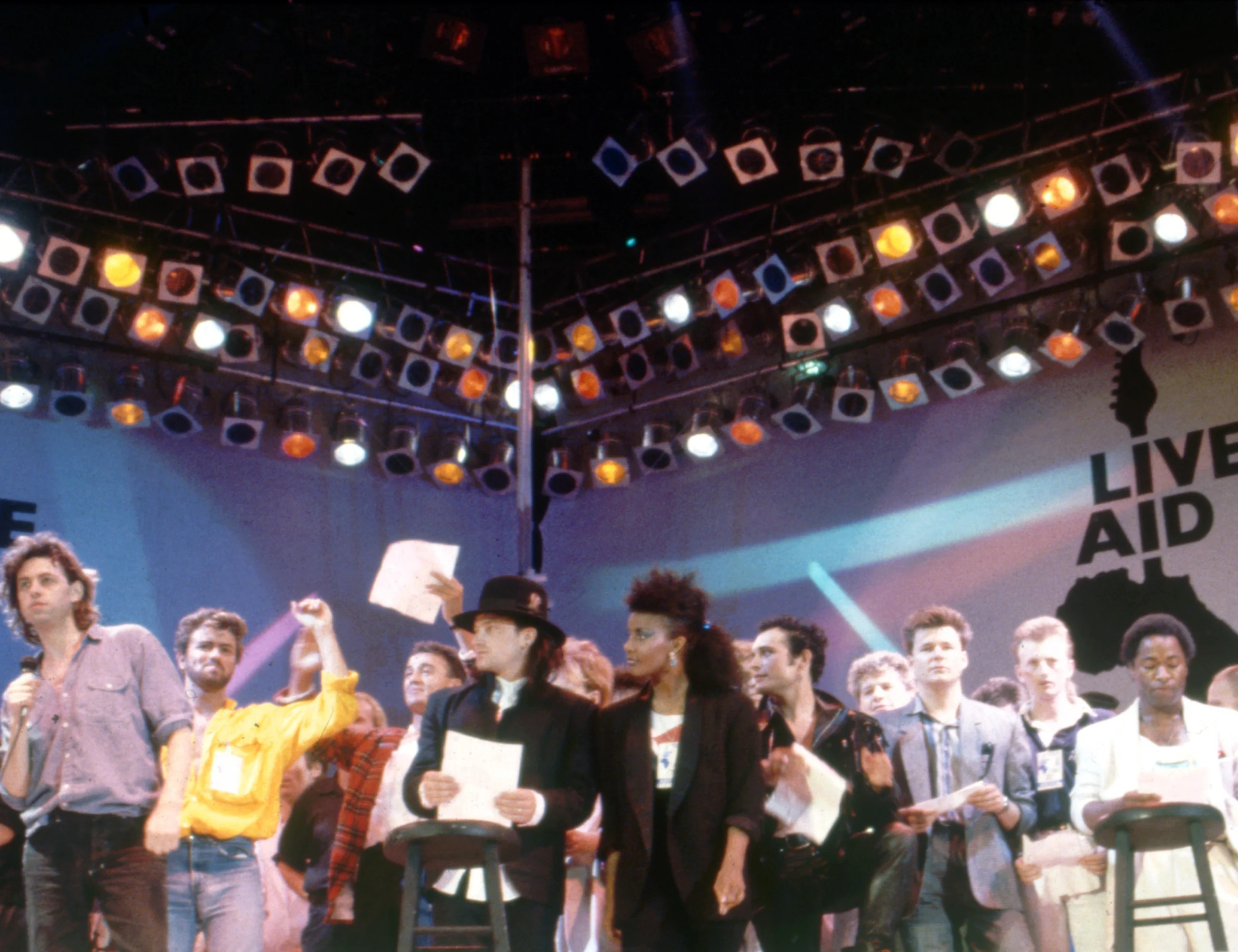

One of Fricke’s early feature assignments as a staff writer for Rolling Stone was to profile The Boomtown Rats’ Bob Geldof, the musician who had co-founded the charity supergroup Band Aid (of “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” fame) and who was organizing Live Aid, two simultaneous mega-concerts to raise money to fight famine in Ethiopia. Fricke followed Geldof for four or five days in London during final preparations for Live Aid, returned to New York to file the story, then flew back to cover Live Aid at Wembley Stadium. During the show, Queen gave one of their greatest live performances and U2 gained fame and prominence with theirs; David Bowie, Paul McCartney, The Who and Elton John were among the other big-name performers. The broadcast from the concerts in London and Philadelphia set a then-record for television viewership (almost 1.9 billion viewers in 150 countries), and Fricke was on stage for the London finale.

[Throughout the concert], there was a great vibe in [Wembley Stadium]. Everybody brought their best energy and optimism. One of the things [Bob] Geldof was really strident about was: Everybody gets four songs, and they gotta be hits. Give the people something to celebrate, and not just the people in Wembley Stadium, but the untold millions that were watching it on television around the world. And that’s what U2 did, what Queen did, what The Who did, what Bowie did.

The PR guy for the show would ferry people back in shifts, take three or four writers backstage to be able to talk to some of the performers, get some quotes, that kind of thing. I got my shot in the late afternoon. I got a chance to talk to Bowie for a few minutes. You didn’t really get great insight because everybody was working, but you got a sense of the vibe and the spirit back there. After about an hour, the PR guy comes back and says, ‘I’ve got to take you back.’ And I said, ‘Look, man, I ain’t leaving. What’s the worst that could happen? They can throw me out.’ He said, ‘Okay, it’s up to you.’

Here’s where not drawing attention to yourself can work. You try to blend in, to observe. At one point McCartney was on stage singing ‘Let It Be,’ and they were getting ready to have everybody come out and sing ‘Do They Know It’s Christmas?’ as the big finish. Sting was handing out lyric sheets, they’re practicing the song. [Security was] about to start shooing people out.

I saw Geldof and said, ‘I realize you’re really busy, but I just want to observe and they’re going to throw me out.’ He was at the end of his rope. He handed me his artist pass card. He said, ‘Here, take this,’ because obviously he didn’t need it. So I put it around my neck and nobody bothered me.

Then, it was time to go out on stage, and as [the musicians] were walking out, I looked down at my pass and thought, ‘What could go wrong?’ I just followed them. I stood behind a couple of guys from Spandau Ballet and sang along. To see that crowd from the stage, and then to see [The Who’s Pete] Townshend and [Paul] McCartney lift Geldof on their shoulders, that was a pretty amazing moment.

When it was all over, I started heading off to the side of the stage and Geldof looked at me and said, ‘What the f— are you doing here?’ And he kind of laughed and then moseyed off. I still have his pass.”

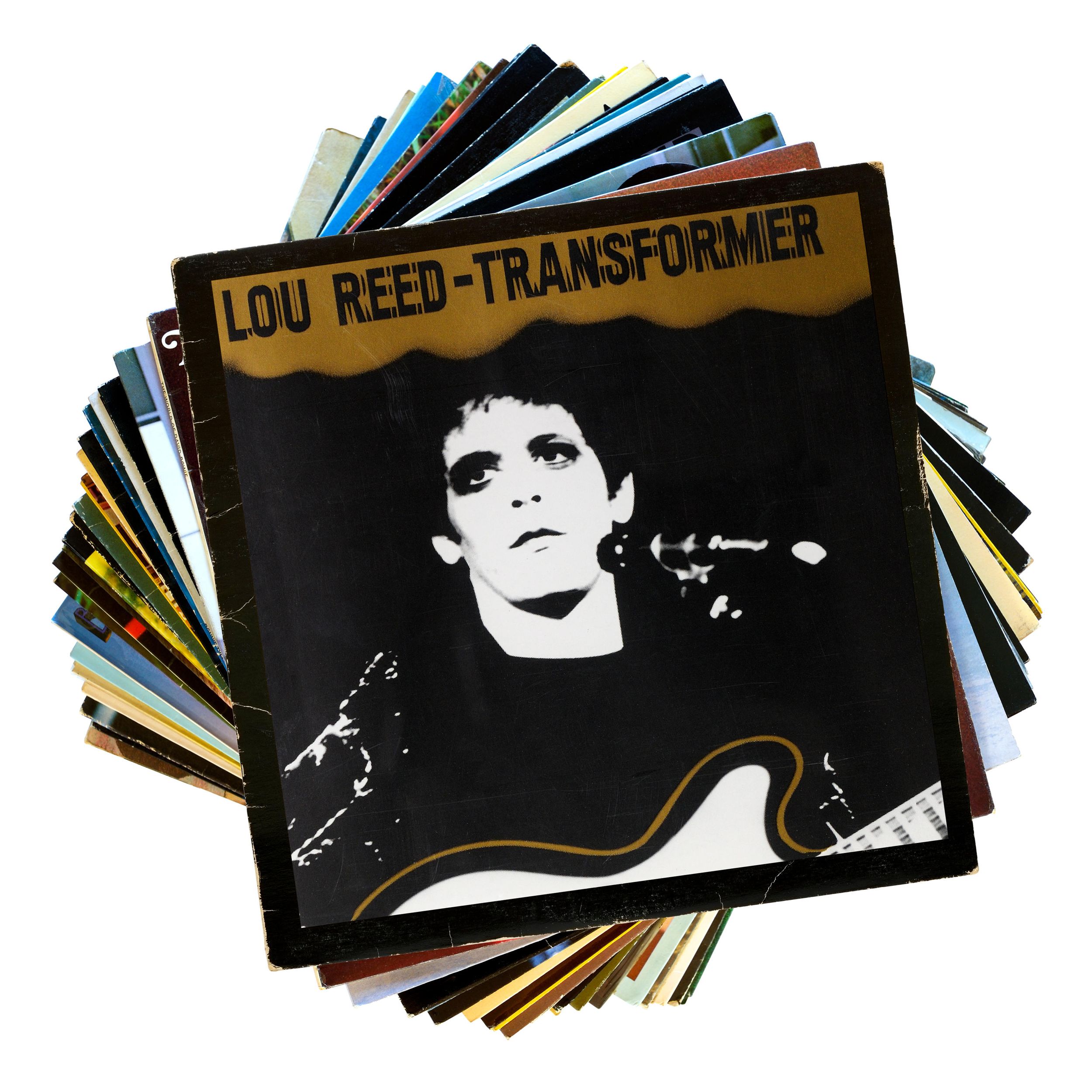

The duration of Fricke’s career has allowed him to work with dozens of musicians repeatedly, building professional relationships that can span decades. One such relationship was with the late Lou Reed, the singer and guitarist for The Velvet Underground whose solo career took off with 1972’s Transformer.

Fricke first interviewed Reed for People in 1984, then wrote a 5,500-word Rolling Stone cover feature in 1989 coinciding with Reed’s acclaimed New York album and tour. Fricke and Reed worked together multiple times on a range of projects including documentaries, liner notes and articles. When Reed died of liver disease in 2013, Fricke wrote the extensive obituary that appeared in Rolling Stone.

Many of these artists are people I talk to over not just days but literal years. Lou Reed, my first interview with him was in ’84, and my last was just a couple of months before he passed away in 2013. One of the biggest stories I did with him was for one of his first really major commercial successes as a solo artist, the album New York, and that was his first cover appearance on Rolling Stone. Yes, the Velvet Underground was a band from like 1965 to 1970, but it wasn’t like I was interviewing him in his sunset years. He was firing bullets in those songs.

I interviewed him quite a lot in his last three decades. At one point, he was being asked by the BBC in England to do a television interview for a big rock and roll history series. They wanted him to talk about glitter rock in the early ’70s because of his record, Transformer, and ‘Walk on the Wild Side,’ and his association with David Bowie. He resisted—he didn’t want to do it. He’s Lou. That’s the way he was. Finally, he agreed to it, but with one caveat: He said, ‘I’ll do it if David Fricke asks the questions.’

We went to a gym in Brooklyn and shot this thing, talked for about an hour. He talked about Bowie, he talked about Transformer, about all the cultural and sexual issues that were involved in that scene. On the way back to Manhattan, we were in the car with his publicist, and Lou says, ‘You know, most people ask me these questions and I get really pissed off. When David asks them, it’s not a problem.’ And I looked at him and said, ‘Lou, it’s all in the delivery.’ I was half kidding, but it’s true. It’s all how you ask it, how you frame it. I’m not there to interrogate somebody. I am there to establish a level of communication and interaction that’s going to be deeper than, ‘Tell me about your latest album. How’s the tour going?’ Any idiot can ask that.

I do a lot of obits—it’s definitely not my favorite thing to do, but it’s an obligation that I have. Somebody like Lou, I knew him quite well and I felt I owed it to him. Certainly, my editors felt, ‘Who else is going to do this and be able to get the kind of people we need to talk to?’ I got Maureen Tucker and Doug Yule from the Velvets. I got everybody who kind of mattered at that moment to talk about him. And I turned that thing around, from the moment he passed away to the moment the issue closed, in 72 hours. And I did it because I knew Lou was up there thinking, ‘You better not f— this up.’”

Fricke served as music editor at Rolling Stone from 1992 to 1995, a stint he ultimately chose to end because it limited the amount of writing he was able to do. One assignment he did take on in that period was a cover interview with Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain. Fricke spoke to him after an October 1993 stop in Chicago on the band’s In Utero tour for a 6,000-word story that ran in the January 27, 1994, issue of Rolling Stone. A little more than two months later, on April 8, Cobain was found dead of a self-inflicted gunshot wound. The interview with Fricke, in which Cobain told him, “I’ve never been happier in my life,” was the last major interview he did.

Later that year, Fricke was the first to interview Cobain’s widow, Courtney Love, about her loss for another Rolling Stone cover story. More than two decades later, he was the first to interview the couple’s only child, Frances Bean Cobain, also for Rolling Stone.

I had always wanted to get a major feature Q&A interview with [Kurt Cobain]—it was a very important format for conversation and insight with an artist. He had done a lot of press and talked to a lot of people, but I didn’t feel that he had talked with that kind of depth. It took a while to get him. He cold-called me at the office one afternoon and said, ‘Hey, it’s Kurt. I know you want to talk to me. I really want to do this. I don’t want to give you the same answers I’m giving everybody else.’ And I said, ‘If that’s where it’s at, then you let me know when you’re ready.’ A few weeks later, I went to Chicago and we ended up spending three hours in the middle of the night after a gig talking at length.

I knew about his subsequent problems, but [when I learned he was dead], I was shocked. There was no other way around it. But having had that shock, I realized I also had work to do—to celebrate the person and tell their story as best you can. The same day, I got a call from Kurt [Loder] because he was over at MTV, and obviously, they were going full steam ahead, covering this and paying tribute to Kurt [Cobain]. He said, ‘Look, man, why don’t you just come over and we’ll talk about him on TV?’ Within about two hours of getting the news, I was live on the air.

The two of us were just talking about Kurt the way we would have talked about him if we were at a gig or a bar. This was a guy who achieved an extraordinary amount of success and created genuinely eternal art and music and left a lot of questions for us to answer in our own lives. And I got a chance to say that, live on TV, on the very day. I still get people who come up to me and say, ‘I saw you on TV the day Kurt died, and the things you said really helped me get through that day.’

Even though my relationship with Kurt wasn’t able to go any further, it probably helped me start another one with Courtney, [which led to] being able to talk to Frances. In 2015, I interviewed her for a cover story about her dad. At one point, I was sitting with her in her living room. I was actually using a cassette recorder at the time, and at one point, I said, ‘You know, that tape recorder in front of you, that’s the same one I interviewed your dad with.’ And she just kind of looked at it, kind of amazed, and took a cell phone picture of it. There was this tape recorder sitting in front of her, and she was talking into the same one that he had done our interview with back in 1993.”

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (dial 988) is a free, confidential service that can provide people in emotional distress with support.

On 9/11, en route to the office from his home on the Upper West Side, Fricke emerged from the subway to find crowds of people standing, slack-jawed, as they watched coverage of what was happening on the southern end of Manhattan on Times Square’s giant screens. Rolling Stone sent staff home at noon that day, but its biweekly format meant the team had less than a week before its next issue would go to print, an issue they’d dedicate to exploring the state of the nation after the terrorist attacks. Fricke’s editors asked him to write about what music meant in the face of such a catastrophic, transformative event; the resulting essay, “Shelter From the Storm,” named for the Bob Dylan song, won an American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers Deems-Taylor Award for music writing in 2002.

I thought long and hard about, ‘How do you listen to music and have it mean anything?’ The world has been pulled out from under your feet, with an enormous and senseless loss of human life. I actually went over to St. Patrick’s Cathedral to sit inside for a little bit, to help sort my head out. I came out and started making some notes about the things that I had started listening to and why. [John] Coltrane, [Jimi] Hendrix, the [Grateful] Dead, U2—they’ve always been part of my listening. But you go back to things because they not only told you something the first time around, but they can reassure you when you need it. And, there are often layers of meaning that can be revealed when circumstances change. The scene [in the essay] where I was walking up Broadway and seeing all the homemade posters people had put up, ‘have you seen so-and-so,’ someone who worked in those buildings and had not come home … the first thing that flashed into my head was Bob Dylan singing ‘Shelter From the Storm.’ He’s somebody I have gone to at different times for different reasons. I think many people in America and around the world went to places of solace and inspiration, places where you get the energy to go forward. When it’s music, you go to the things that speak to you most clearly and most profoundly. And for me—in that case and in many cases before and since—it’s going to be Hendrix. It’s going to be Coltrane. It’s going to be Miles [Davis]. It’s going to be Joni Mitchell. It’s going to be Bono. It’s going to be Rage Against the Machine or Kurt [Cobain] and Nirvana. It’s going to be Hank Williams. It’s going to be Patsy Cline. It’s going to be Memphis Minnie and Janis Joplin. I go where I know that there is a place of refuge, but also a place to start over from.”

Another artist Fricke has worked with multiple times over the decades is ex-Beatle Paul McCartney, including interviews for Rolling Stone cover stories in 1990 and 2016. The more recent conversation took place in London as McCartney prepared to embark on a tour of the United States. One of the reasons Fricke got into music journalism was his own curiosity about the musicians themselves and how they approached making their music, and in this session, McCartney illuminated that in a highly memorable fashion.

John Lennon is known as the avant-garde personality of the Beatles, partly because of his life with Yoko [Ono] and the way they made art together, but McCartney was the guy who actually was bringing in a lot of the early avant-garde influences in the ’60s, even before Lennon. He’s also somebody who’s very keen to talk about the process of writing and conceiving something.

When I was interviewing him in 2016, I was asking him about songwriting: ‘How do you start? What’s going through your head? What was it like as a teenager to write songs, to try to find a way into this form of expression? When you haven’t written songs before, when you don’t know how to start, what do you start with?’

He started explaining about writing with John Lennon when they were teenagers, before anybody knew who they were, when they were 15 or 16 years old. He said, ‘I’ll give you an example,’ and he picks up an acoustic guitar that’s next to him. He starts playing, singing a song that he and John had written when they were teenagers in Liverpool. It was just a verse and a chorus, but it was a song they had never recorded.

So he’s actually playing for me an unreleased Beatles song from, let’s say, maybe 1958. Like, ‘Here’s an example of something we put together really quickly.’ That was a personal recital. That was a song that, outside of himself and John and probably a very small circle of people, no one had ever heard. He wasn’t doing that to show off; he was doing that to explain the process. And I happened to be recording the interview. I had the only copy of that performance of that song in that moment. And you can’t make sh– like that up.”