A Community Effort

What does it take to change the campus climate surrounding race at a predominantly white institution? True transformation starts with individual students, faculty, staff and alumni who push themselves and their peers—and by extension, the College—toward anti-racism, equity and an understanding that this work is never finished.

Photos by Ryan Hulvat and Alaina Lutkitz

The speech began like any other, with Visiting Professor of Political Science and Africana Studies Justin Rose thanking the attendees and organizers of the 2013 Martin Luther King Jr. Day event at which he was about to speak. In fact, it took more than 10 minutes for Rose’s speech to reach its turning point—the moment when it started to become clear that faculty, staff and alumni of the College might still be talking about his words more than seven years later.

“For those of you who don’t know the term ‘Muhlenberg Nice,’ it refers to the behavior of the students at Muhlenberg College,” Rose told the crowd in the Seegers Union Event Space. “It says, in short, that they would rather be nice than to engage in confrontation.”

He went on to explain how he had tried to be Muhlenberg Nice and “a good Negro” during his first semester as a Consortium for Faculty Diversity (CFD) Fellow, a one-year appointment that left him feeling conflicted. How was he to respond, he wondered, at a predominantly white institution with predominantly white faculty when students of color sought him out as a mentor or confidant? (At the time, only 11 full-time faculty identified as minority.) How close should he allow himself to become to those students when he knew that his time at the College would be limited to the 2012-2013 academic year?

One thing his speech did was to inform students that he’d accepted a tenure-track job at another CFD member institution, so he’d be leaving at the end of his one-year term with the College. Once students realized that, the speech became, in the words of Kayla Brown ’14, “the greatest parting gift he could give … He was so raw and truthful about what so many [students of color] were already thinking.”

Rose’s speech included statements like “I’m claiming that the College does not really care about diversity, but that its goal is only to appear to care about diversity” and “there is not one faculty member or administrator of color who is happy with the climate surrounding diversity here at the College.” Roberta Meek ’06 P’14 GP’20, a lecturer in media & communication and Africana studies and former lecturer in history, sat in the front row as Rose spoke. She remembers hearing “amens” and the like coming from students behind her and noticing the uncomfortable body language of administrators in the front row across the aisle.

When Rose finished, “the Black students in that audience, the folks who were part of the [Black Students Association (BSA)] who helped to put the celebration together, jumped to their feet,” Meek says. “There was kind of a roar from them. It was just an incredibly powerful moment.”

It marked the end of Muhlenberg Nice for some students in the audience. No longer would they allow race to be something discussed only within their affinity groups, inside the Multicultural Center or with a small, trusted circle of faculty and staff. Rose’s speech began a chain of events that would bring together 13 student leaders, including Brown, in a coalition they’d call the Diversity Vanguard, which brought a list of demands to then-President Randy Helm. The group’s action directly resulted in the creation of the College’s first Diversity Strategic Plan, which has achieved, among other things, an increase in resources for the Office of Multicultural Life, an expansion of the College’s Emerging Leaders Program for students from historically underrepresented groups and an increase in hiring of faculty of color.

And yet, Muhlenberg has struggled to retain faculty of color—especially Black faculty—and in April 2019, concerns about bias in the College’s judicial process inspired dozens of students of color and their allies to protest. While it’s true that the Diversity Vanguard and the Diversity Strategic Plan helped the College take steps in the right direction, and that the plan built upon work that came before it, Muhlenberg has continued to be a place where some community members of color feel unsupported.

![“The Black students in that audience, the folks who were part of the [Black Students Association (BSA)] who helped to put the celebration together, jumped to their feet. There was kind of a roar from them. It was just an incredibly powerful moment.” Roberta Meek’06 P’14 GP’20, Lecturer in Media & Communication and Africana Studies](https://magazine.muhlenberg.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/CommunityEffort5-1-1024x238.webp)

Current events demonstrate that this is far from just an institutional problem—the entire country is reckoning with issues of race. The COVID-19 pandemic has devastated Black and brown communities across the United States, with Black people dying at more than twice the rate of white people. High-profile cases of police brutality have sustained nationwide Black Lives Matter demonstrations that began in late May.

In June, a group of eight Black faculty wrote a letter and action plan to the Muhlenberg community with requests that were similar to those the Diversity Vanguard students made seven years before—more tenure-track Black faculty and faculty of color, a further expansion of the Emerging Leaders Program, a stronger diversity curricular requirement that would see all students educated on issues of race and power structures. This time, though, there seems to be a greater understanding of what it will take to generate a palpable shift in the campus climate.

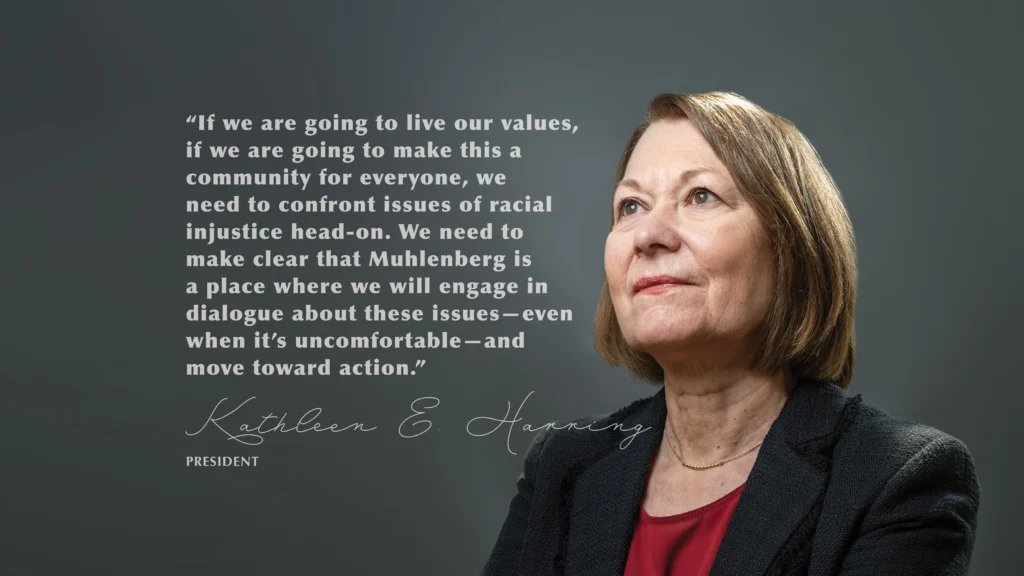

“The College is committed to being open and transparent about what we’ve done and what work we still need to do as a community—and that’s the key thing. I don’t know if we have framed the work that needed to be done as community work in the past,” says President Kathleen E. Harring. “In thinking about how true transformation takes place, it has to be a community effort. In order to truly have authentic, meaningful change, everyone needs to be working toward the same goals. The bottom line is, the institution is our people, and in order for true change to occur, people need to be committed to making that change and to actually implementing it.”

![“He was so raw and truthful about what so many [students of color] were already thinking.” Kayla Brown’14](https://magazine.muhlenberg.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/CommunityEffort-2-1024x576.webp)

Conditions on Campus

In the semesters leading up to Rose’s Martin Luther King Jr. Day speech, Director of Multicultural Life Robin Riley-Casey remembers hearing from students of color on campus who were struggling. (They were also relatively few and far between—just 2.7 percent of students identified as Black and 4.3 percent as Hispanic/Latino, compared to 4.3 percent as Black and 9.2 percent as Hispanic/Latino today.) She says they would experience microaggressions—comments or questions from faculty, staff or fellow students that, while not overtly racist, made them feel singled out due to their race or ethnicity. At the time, the College lacked a formal reporting structure for any kind of bias incidents. Students would often bring their stories to Riley-Casey, who worked to handle these reports with then-Vice President for Student Affairs and Dean of Students Karen Green. It was “very ad hoc,” Riley-Casey says. And not all aggressions were micro: Rose recalls hearing of a then-recent incident in which someone had used the n-word on campus when he came for his interview in spring of 2012.

Emeley Rodriguez ’15, who would go on to be part of the Diversity Vanguard, remembers a white student asking her how many people she’d seen get shot while growing up in the Bronx. “Some of the questions I’d get … The ignorance was so prevalent,” Rodriguez says. “It was a bigger problem than just fellow students. I have stories for days.”

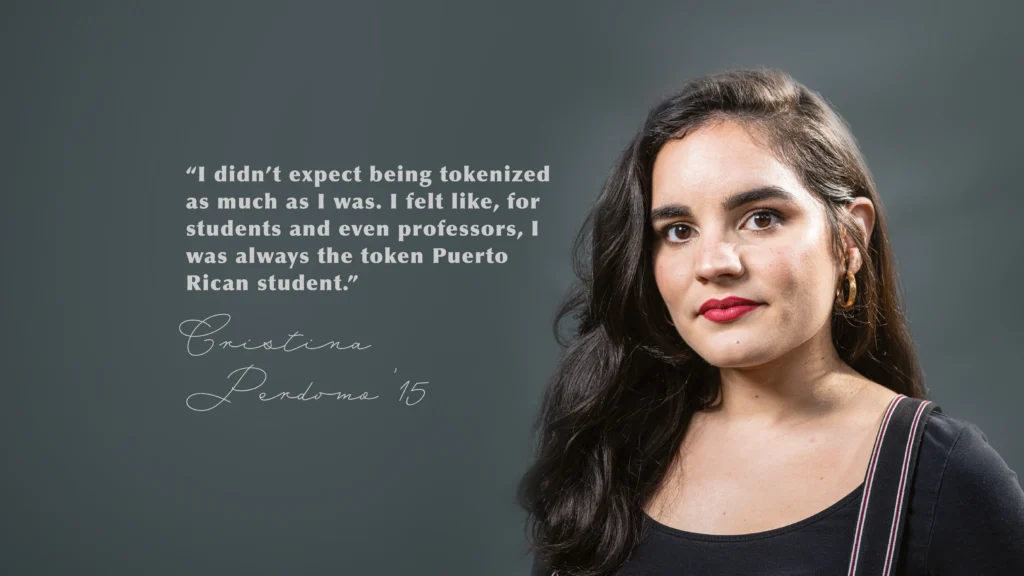

Her friend, roommate and fellow Diversity Vanguard member Cristina Perdomo ’15 was one of two students in her class recruited from Puerto Rico. She remembers hearing surprised comments like, “You don’t have an accent! You’re so articulate and intelligent.” She felt students and faculty treated her as the “token Puerto Rican student” and found a safe space in the Multicultural Center and its affinity groups. (She was co-president of Comunidad Latina when the Diversity Vanguard formed.)

Both were in the audience for Rose’s speech, which took place on a Sunday afternoon. As the crowd mingled afterward, white students expressed shock at what he said—they largely did not know how students, faculty and staff of color were feeling—and students of color expressed shock that he’d said those things in a public forum. The discussion percolated on campus for a few days. Then, that Wednesday, Helm sent out a campus-wide email with the subject line, “Request for Comments: A New Draft of Muhlenberg’s Diversity Statement.” In it, he shared a recent revision of the statement, which had first been released in 2006, and invited feedback. He included no mention of Rose’s speech, the ensuing discussion or further action items to address diversity, equity and inclusion on campus.

“I think [Rose’s] speech was very powerful. It really motivated and energized the students on an important issue. Having said that, when the president is going to issue a call to the community to discuss something, I wanted it to be about the important issue,” Helm says of the email. “I didn’t want to be taking sides on a speech that raised the issue, because the speech itself was not the issue. The issue was the issue. Diversity and the campus climate was the issue.”

Some read the email differently. For example, Rodriguez describes it as “an attempt to put a Band-Aid over a small cut, and somehow he made the cut bigger.” Students came to find Riley-Casey in the Multicultural Center, and they were angry. She recalls marching with students over to Trexler Library, where Meek was teaching, and rapping on the classroom window. The students had drafted a letter of outrage, and they wanted Meek to sign it, and they wanted to hand-deliver it to Helm’s house that night. Meek met with the group after class and encouraged the students to slow down and think strategically.

Mel Ferrara ’15, who was co-president of Students for Queer Advocacy at the time and is now an adjunct professor of women’s & gender studies, remembers receiving a text from the other co-president, Luis Garcia, summoning them to campus. That night, Ferrara and the other affinity group leaders—now calling themselves the Diversity Vanguard—worked with Riley-Casey and Meek to draft an email to Helm requesting a meeting.

The next evening, the Diversity Vanguard hosted an open house at the Multicultural Center for all students to discuss suggestions for improving diversity, equity and inclusion on campus. About 80 students showed up.

“I don’t think I realized we had that many people who cared,” says Brown, who was president of the Multicultural Council at the time. “First of all, 80 people couldn’t fit in the Multicultural Center. We were hot and on top of each other, but it was really nice to see. Even though it was 80 compared to how big the campus is, it was 80 people we didn’t even know we had.”

The Diversity Vanguard helped whittle down the ideas that came out of that meeting into a list of 32 goals, most of which dealt with issues of race and ethnicity, that represented the overall spirit of the students’ requests. Then, they set about preparing for their meeting with Helm, which would take place the following week in the Multicultural Center.

A Plan Takes Shape

For some of the Diversity Vanguard students, the February 1, 2013, meeting with Helm and his senior staff would be the first of many they’d attend with him. The most tangible result of the meeting would be Helm’s commitment to creating a strategic plan on diversity, with four students from the group to serve on the planning committee. That day, the students pitched their ideas to the attendees: the administrators as well as members of the faculty coalition that had announced support for the students and allies like Meek, Riley-Casey and Cindy Amaya Santiago ’01, who was then senior associate director of admissions and coordinator of multicultural recruitment.

“I knew the students had been getting ready to be part of this conversation, but they impressed the heck out of me that day,” Amaya Santiago says. “They came ready with their talking points and ready to engage. They came ready to not just say, ‘You’re wrong, as an institution,’ but they came ready to suggest actionable items.”

Soon, the Diversity Vanguard students were meeting again to determine who would sit on the diversity strategic planning committee. They wanted to represent as many affinity groups as possible with their limited number of slots and also acknowledge that the committee would be a time commitment not everyone could manage. The group selected Brown (who was also a member of the BSA), Ferrara (who also belonged to the Feminist Collective), Garcia and Zak Tanne ’14, co-president of Comunidad Latina. When Ferrara went abroad in the spring of 2014, Rodriguez, who was president of the multicultural sorority, Theta Nu Xi, and a member of Comunidad Latina, took their place on the committee.

The committee would meet 19 times between April 2013 and April 2014. In addition to the Diversity Vanguard students, its membership included six faculty members, a Student Government Association representative (Adelaide Matthew Dicken ’14), nine staff (including Helm, who chaired the committee, and Harring, who was then dean of institutional assessment & academic planning), a trustee representative (Barbara Crossette ’63) and an alumni representative (Adrian Shanker ’09).

While the committee members had a shared objective in theory, in practice, even getting the group to agree upon how it should define diversity was a contentious, multi-meeting process. The Diversity Vanguard students and their staff and faculty allies repeatedly stated that issues of race and ethnicity should be the committee’s focus; Helm repeatedly challenged them.

“I was pretty clear in my own mind that race, ethnicity and class were the central issues, but I also believed that to definitively exclude other marginalized groups would invite division and acrimony, distracting us from our important work and turning groups that should be natural allies against each other,” Helm says today.

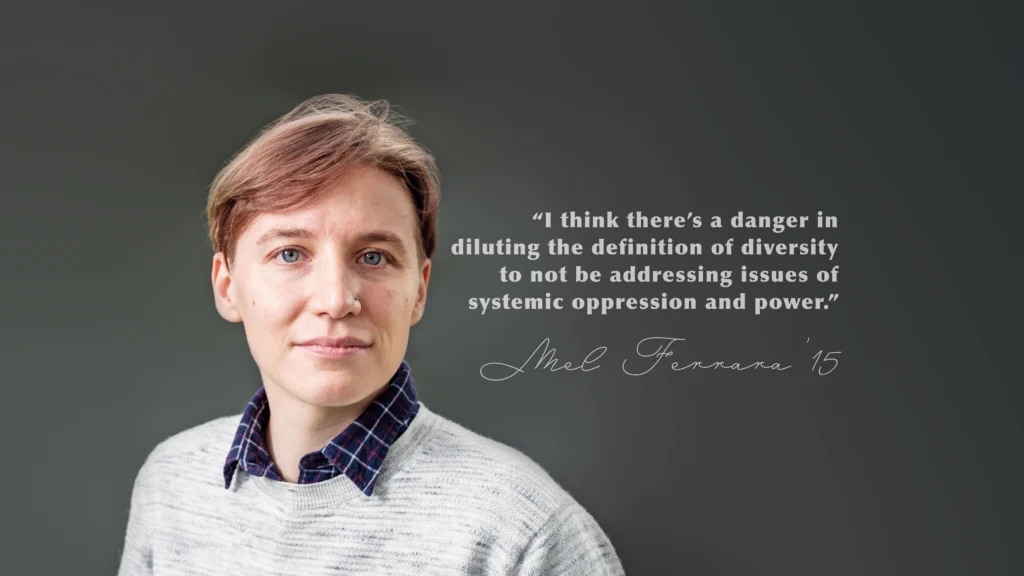

Ferrara recalls their attempts to explain the concept of intersectionality: that in working to dismantle racism, the group would simultaneously be working to dismantle sexism, homophobia and other types of bias.

“I think there’s a danger in diluting the definition of diversity to not be addressing issues of systemic oppression and power,” they say. “I felt like that was one place for me as a white, queer and trans student to try to leverage the privilege of my whiteness to try to talk to President Helm specifically: ‘You’re trying to say this isn’t going to work for students who are experiencing homophobia and transphobia. I’m telling you it is.’ There was a fundamental ideological disconnection between certain members of the administration, students and faculty.”

Amaya Santiago characterizes the meetings as full of misunderstandings, difficult conversations and heated emotions. This was inevitable, given the subject matter and the diversity of the strategic planning group itself, but the administration recognized the importance of having these disparate voices at the table.

“You need to have a broad swath of the community, from top to bottom, because diversity should be woven through everything that is done at an institution,” Green says. “With a large group, the process becomes even more convoluted and slow, but that needs to occur. This group had not been together to talk about these very contentious issues, so we needed to unpack the uneasiness about talking about race … Yes, it’s uncomfortable. Yes, people are defensive. Yes, people are speaking their truth to power. But if we’re going to make a difference in an institution, these are the steps that must take place.”

The alumni who were students at the time recall feeling frustrated—at the pace of the work, that they were not feeling heard, and finally, by the scope of the plan, which would encompass some but not all of the original student demands: “As the process went on, it became clear that we’re really going to just be the first step,” Tanne says. “This isn’t going to be this massive change we thought it might be.”

“It was hard and sometimes contentious. And yes, I understand that some were not happy with the way things unfolded,” Harring says. “It didn’t pave the road the students wanted, but it did pave the road to change. The process was successful at creating a strategic plan to improve diversity and inclusion at Muhlenberg and the progress that the College has made over the past seven years—including our current commitment to anti-racism—is a direct result of those difficult conversations.”

From Plan to Action

The Diversity Strategic Plan, approved by the Board of Trustees in October 2014, did have tangible effects. It created the position of assistant director of multicultural life (now held by Kiyaana Cox Jones) and expanded the Emerging Leaders Program. It established stipends for students who otherwise would not be financially able to participate in short-term study abroad and alternative spring break opportunities. It led to changes in hiring practices that have helped increase the percentage of full-time faculty who identify as minority from 6.6 percent in the 2012-2013 academic year to 13.7 percent in 2019-2020. It created the position of associate dean for diversity initiatives, which was later expanded to the full-time position of associate provost for faculty and diversity initiatives. Brooke Vick has held that position since July 2018.

“Part of my priority [when I started] was getting us organized and focused around what we have accomplished, what is left to do and what we should prioritize going forward,” Vick says.

One of her top priorities is ensuring the College retains faculty of color once they’re hired. For privacy reasons, the College does not disclose how employees identify in any specific racial/ethnic category; the public-facing Common Data Set uses the nonspecific term “minority faculty” to include those “who designate themselves as Black, non-Hispanic; American Indian or Alaska Native; Asian, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander; or Hispanic.” However, the institutional data from 2016-2019 show a relatively flat number of Black faculty in particular—even as the College hires more, it loses them in roughly equal numbers. When Vick arrived, several Black faculty had recently departed.

“It wasn’t just that they left—they left and made a statement about why they were leaving,” says Vick, who has promoted connections between faculty of color (via social gatherings, email listservs and a two-day retreat held in partnership with other Pennsylvania Consortium for the Liberal Arts institutions) to begin working toward greater retention. “I wish I could say, ‘In two years, I have solved this issue.’”

Other work to change the systems and processes that disadvantage students, faculty and staff of color has built off the work of the Diversity Strategic Plan. For example, the plan called for an outside consultant to review all College policies. That process led to a strengthening of the hate/bias policy and a clear, online reporting method for such incidents. Meanwhile, the College’s longtime director of Title IX was retiring, so Vice President for Student Affairs and Dean of Students Allison Gulati used the opportunity to expand that role.

“Students wanted to make sure our responses to hate and bias were equal to our gender violence response,” she says. Since June 2018, Associate Dean of Students and Director of Equity and Title IX Lin-Chi Wang has been the point person to field reports of bias, discrimination, harassment and sexual misconduct.

Gulati’s office has also prioritized “supporting all students, but particularly underrepresented students, experiencing financial hardships.” Three main initiatives work toward this goal: the Muhlenberg Useful Living Essentials (M.U.L.E.) Community Cabinet, which provides food and hygiene items for students; Experiential Learning Grants, which support curricular and co-curricular experiences like conference attendance; and the Emergency Grant Fund, which launched in summer 2019 and has distributed $80,000 to 230 students since.

“It is important that we’re always thinking about how to be more equitable and inclusive for students of all backgrounds and experiences,” Gulati says. “When we see one population hurting or being disenfranchised more than another, we need to focus our attention toward that in a more direct way.”

The continuation of student activism on issues of racial injustice on campus shows that, despite the progress the College has made, it still has more work to do. Associate Director of Admissions and Coordinator of Transfer Admissions Eric Thompson ’10 has witnessed Muhlenberg’s evolution since he started as a first-year student in 2006, but he hears today’s students of color talking about their experiences in the same ways he and his peers did.

“I’m a staff mentor for Emerging Leaders and I direct the Gospel Choir, which is a diverse group of students. When students are protesting that they don’t have resources or aren’t getting support, I know I’m out here giving support. It was hard to take,” he says of the April 2019 demonstration. “I love the student advocacy. It’s just frustrating that 13 or 14 years later, students are still feeling this way.”

A Turbulent 2020

April 2019 feels like a lifetime ago, a time when the biggest health threat to Muhlenberg was a potential mumps outbreak that never materialized. In April 2019, campus was home to all four classes of Muhlenberg students (not just first-years), and faculty and staff were expected to teach and work in person. An individual walking down Academic Row wearing a mask would be the exception rather than the rule. Nationally, COVID-19 and the disproportionate burden it has placed on communities of color created an environment ripe for the Black Lives Matter demonstrations that have taken place across the country and generated an unprecedented amount of support.

“Part of what makes this movement different is it’s more widespread,” says Emanuela Kucik, assistant professor of English and Africana studies, co-director of Africana studies and one of the Black faculty letter’s co-authors. “There’s a larger number of people from a broad range of racial and ethnic backgrounds involved. That’s created a national moment that has urged schools to respond in meaningful ways.”

While the College did respond publicly—including several community messages from Harring and a statement from the Board of Trustees affirming the College “will do better and more to dismantle racism and injustice”—it also committed to actions that advanced goals shared by the College and Black faculty. Harring pledged to increase funding and resources for the Office of Multicultural Life and the Emerging Leaders Program. She also announced approval for hiring two tenure-track faculty positions with joint appointments in Africana studies to expand the program.

Kucik and Connie Wolfe, the other co-director of Africana studies and an associate professor of psychology, are using this academic year to enrich and restructure the program (by adding a community engagement component, beginning to build a Center for Anti-Racism and establishing Africana studies as a central vehicle for programming that responds to the current moment, among other things) and have chosen to conduct the faculty searches next fall. On the programming front, Kucik and Wolfe co-organized a number of racial justice events that were co-sponsored by the Africana Studies Program and held virtually.

Harring also asked the President’s Diversity Advisory Council (PDAC), which Vick chairs, to produce a list of diversity, equity and inclusion priorities for the current moment. PDAC drew upon previously discussed initiatives (including the incomplete items from the Diversity Strategic Plan) and discussed new ideas before making its recommendations. Of the six top priorities, three concern facilitating education on issues of white supremacy and structural racism to reach all members of the campus community—students, faculty and staff.

“What education does is give people the background and the context to understand what’s happening around them, and it expands their perspectives,” Kucik says.

For students, this educational component would take place via required courses in race and power structures and a proposed requirement in extracurricular activities related to racial justice to carry their education on the topic beyond the classroom. Muhlenberg’s Academic Policy Committee and the authors of the Black faculty letter are collaborating to move this initiative forward. For faculty and staff, one of Vick’s priorities for this academic year is to develop a curriculum about anti-racism, inclusion and cultural competency to be offered at least annually. She envisions a tiered system—people who are early in their learning could take a session tailored to beginners, with the opportunity to move on to intermediate and advanced sessions later.

“Without understanding the dynamics, institutions and systems that shape our individual experiences, we’re not able to come together thoughtfully,” Vick says, “and without that education, we’re more likely to be harming one another out of ignorance.”

But Muhlenberg students, faculty, staff and alumni are not just waiting for the College to present them with opportunities to learn more about racial injustice and to be part of the solution. The Alumni Board has committed to including diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives in the strategic plans for each of its six committees. Riley-Casey says that requests from student groups for workshops on issues like implicit bias and making their facilities more anti-racist and inclusive have skyrocketed. Vick, too, says that academic and administrative departments have reached out to her for training and information on an unprecedented scale.

“What has changed is there is a lot more higher-level thinking about this. Previously, this work had been more siloed. There had been the usual suspects always doing this work,” Vick says. “Now, everybody is feeling an increased level of responsibility to be accountable on these things.”

What We Stand For

While that happens on a community level, what is happening on an institutional level is an intentional commitment to making the College’s values abundantly clear and to having the difficult but important conversations—an attitude that is the antithesis of “Muhlenberg Nice.”

“If we are going to live our values, if we are going to make this a community for everyone, we need to confront issues of racial injustice head-on. We need to make clear that Muhlenberg is a place where we will engage in dialogue about these issues—even when it’s uncomfortable—and move toward action,” Harring says.

This commitment was put to the test in late summer. Some students noticed that the ’Berg Bookshop was selling masks adorned with the “thin blue line” flag, which has been viewed as a symbol of solidarity with law enforcement but co-opted by groups that stand in opposition to the movement to address racial injustice and violence against Black and brown communities. The bookstore does not normally sell merchandise that supports any political or social cause, and when students shared their concerns, the administration ensured the product’s removal. Chief Business Officer and Treasurer Kent Dyer sent a community message in mid-August addressing the issue and detailing what would happen next, including further discussion of the incident.

A dialogue between the students and the ’Berg Bookshop manager took place in mid-September, was facilitated by Riley-Casey and Gulati and went well, says Riley-Casey. In October, Jones facilitated a meeting between Riley-Casey and Campus Safety; it was an opportunity for Riley-Casey to share why she asked for the masks to be removed and for officers to listen and respond.

![“All our responsibility is to the students. That was my intent, to protect—as [Campus Safety officers] do—our students, when they called upon me.” Robin Riley-Casey, Director of Multicultural Life](https://magazine.muhlenberg.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/CommunityEffort15-1024x230.webp)

“All our responsibility is to the students,” she says. “That was my intent, to protect—as [Campus Safety officers] do—our students, when they called upon me. I have a duty to make the campus aware when controversial imagery or language weakens the bonds of our community. I think the officers heard that. They may not agree with the way I handled it, but they heard that and understood.”

Riley-Casey says she is “really quite impressed with the College” for its handling of the mask situation. It acted to remove the product in question and to ensure students, faculty, staff and alumni understood what had taken place. It supported opportunities for community members with different perspectives to engage in dialogue and restore trust. And it did not back down, even in the face of aggressive pushback following national media coverage of the incident. This is the way forward, says Harring.

“We need to be open and transparent about our values and engage in community dialogue about how our values inform the work we do every day at the College,” she says. “Communicating the initiatives, the actions and the community progress that align with our values is critical for not just our campus community but for the greater community to understand who we are and what we stand for.”