Honored

Muhlenberg’s honors programs expose students to new ideas and challenges so they can enter the world ready to lead and make a positive change.

In 1988, Ted Schick, professor of philosophy, started the Muhlenberg Scholars program, the first merit-based honors program unique to the College. “The purpose was to attract and retain exceptional students by providing unique opportunities for intellectual exploration, growth and development,” explains Ranajoy Ray-Chaudhuri, assistant professor of economics and current director of the Muhlenberg Scholars Honors Program.

Muhlenberg offers three other honors programs to “provide an opportunity for students to engage beyond the classroom and to think critically about the diversity of the human experience from multiple disciplinary lenses,” says Dean of Academic Life Michele Deegan. “They learn to develop their critical thinking and reasoning skills in order to be more agile, engaged citizens.”

Academically, this involves courses designed to complement and enhance the College’s liberal arts requirements. Socially, the honors programs facilitate making interdisciplinary connections with students, faculty and guest speakers. The ultimate goal is to help students thrive after they graduate.

“Through program requirements, they’re exposed to opportunities to wrestle with the complexities of our world during their time at Muhlenberg,” Deegan says. “They develop a deeper understanding of the challenges locally, nationally and globally and are more prepared to jump into graduate school or careers with greater awareness of the diversity of the human condition and experience.”

“This program has prompted me to take initiative. I have learned how to organize my thoughts, research and present my findings in a coherent and effective manner, and the connections I’ve made with students and professors have supported me in achieving my goals.”

—Lindsay Scott ’22

The Muhlenberg Scholars program, designed for intellectually curious students across disciplines, has tested Lindsay Scott ’22, a biology major and statistics minor, in the most positive ways. “Through my Scholars seminars, I have been exposed to the beliefs of other cultures. The most challenging experience has been trying to remain open to new ideas and ways of thinking,” she says.

The faculty teaching Muhlenberg Scholars courses purposely emphasize original-source materials rather than textbooks to facilitate this shift. “They collate a reading list from a range of sources such as journal articles, research reports, data sets, newspapers, magazines and audiovisual materials. Even in instances when these are not purely objective, they are intentionally chosen to represent a multitude of perspectives,” Ray-Chaudhuri explains. This way, “readers synthesize the information and come to their own conclusions regarding the content rather than rely on someone else’s interpretation.”

After a first-year seminar intended to develop analytical writing skills, sophomores choose an academic project. Scott wrote a paper on the relationship between DNA and the ethical issues surrounding collecting DNA samples. She spent an entire semester researching and writing. “The final project is something that I am very proud of, and it was amazing to see all of my hard work come together,” she says.

This year was an integrative seminar on immigration of all races and ethnicities, and next year will be the senior capstone seminar. “The goal for these Scholars-only classes is to forge an intellectual community as well as develop specific marketable skills,” Ray-Chaudhuri says. Scott enjoys both the diversity of the seminars and the ability to collaborate with students outside of her science classes. “I have been in class with the same 20 students for four years. This helps build camaraderie, and it allows all of us to be very open and honest with each other,” she says. “It is very rewarding to be in class with other students who care about learning and becoming more well-rounded individuals.”

But it’s not all work. Muhlenberg Scholars also have the chance to attend exclusive talks by speakers drawn from within and beyond the campus and end-of-semester dinners. Last year included a session organized by Christopher Herrick, professor of political science and the director of prestigious awards, on postgraduate awards—such as the Fulbright, Gates Cambridge, Marshall and Rhodes Scholars programs—and how to successfully prepare to compete for them.

With all of this under her belt, Scott says she’s grown as a student and as a person. “This program has prompted me to take initiative. I have learned how to organize my thoughts, research and present my findings in a coherent and effective manner, and the connections I’ve made with students and professors have supported me in achieving my goals,” she says. “The various projects and breadth of knowledge that I’ve gained have given me the confidence to apply to medical school, and I know these skills will be useful if I choose to take a research year.”

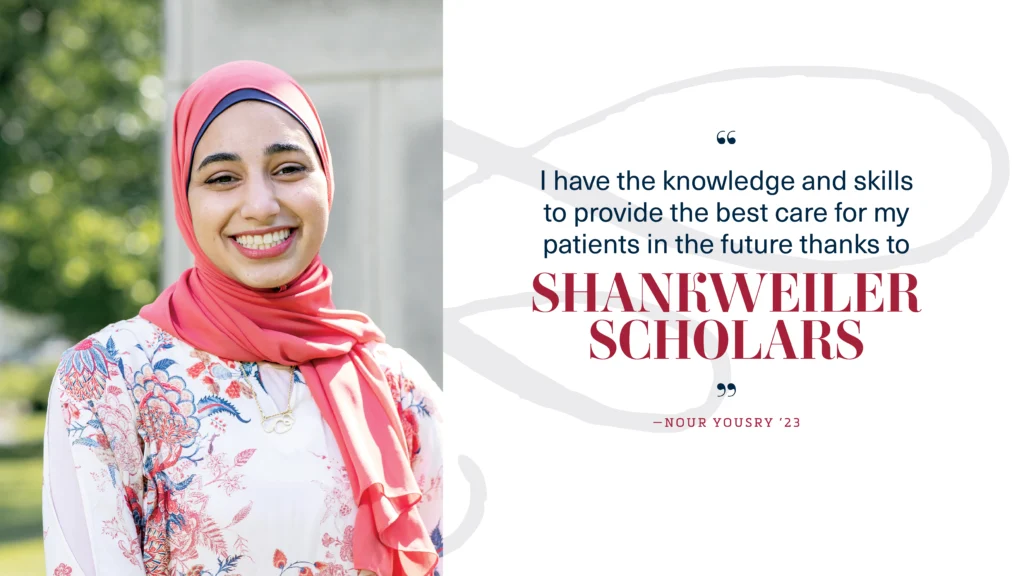

A quality doctor is trained on diagnoses, procedures and standard patient care, but an excellent physician can do those things while ensuring patients are heard and supported, says public health major Nour Yousry ’23. As a Shankweiler Scholar, she feels confident that she’s on the path to becoming this kind of doctor.

“I realized early on that the field of medicine ties so many aspects of various disciplines, such as history, religion, anthropology, psychology and sociology,” Yousry says. No wonder Shankweiler Scholars, which welcomed its first cohort of students in 2019, attracted her.

“Shankweiler Scholars are not only preparing for a successful career in medicine, they’re encouraged and challenged to draw connections between their premedical interests and other aspects of our liberal arts curriculum to gain a better understanding of how the practice of medicine truly is a human endeavor,” explains Assistant Professor of Anthropology Casey James Miller, who’s been director of the program since 2019.

Students start with a fall seminar, Medicine as a Human Endeavor, to introduce them to the Shankweiler philosophy. The program’s faculty experts come from a wide range of disciplines, including religion, anthropology, history, psychology and public health.

In their second year, Shankweiler Scholars take Medicine and Society. Working with a faculty mentor, students invite a guest speaker to give a public lecture on a topic related to medicine. They also read and discuss literature written by that speaker. Yousry looks forward to hearing from Johns Hopkins University’s Travis Rieder, director of the Berman Institute of Bioethics, who will talk about his research regarding the opioid pandemic and its impacts on the health-care system and society.

“This is an incredibly unique experience, as it allows our class to work together to invite a scholar that may enlighten the minds of Muhlenberg students and staff,” Yousry says. “The Shankweiler Scholars cohort plans on discussing various healthcare disparities and the opioid pandemic with Dr. Rieder, in addition to inviting the wider campus community to his talk.”

Students also work on a self-designed curriculum to explore their own interests in medicine and the liberal arts. “My curriculum seeks to explore the experiences of people with various socioeconomic statuses in the field of medicine,” Yousry says. “By identifying the disparities in access to medicine and medical care, I aim to better equip myself with the knowledge and tools to tackle these issues through my current volunteer experiences, imminent medical studies and future practice as a medical physician.”

When this individualized course of study wraps, students share their learnings with each other during their senior year.

Yousry feels empowered by her experiences as a Shankweiler Scholar. “I have been able to combine so many disciplines into the field of medicine, which will give me the knowledge and skills to deal with various patient scenarios and circumstances and provide the best care for my patients in the future,” she says.

“Shankweiler Scholars are not only preparing for a successful career in medicine, they’re encouraged and challenged to draw connections between their premedical interests and other aspects of our liberal arts curriculum to gain a better understanding of how the practice of medicine truly is a human endeavor.”

—Casey James Miller, assistant professor of anthropology

“Encouraging our collaboration deeply shaped my approaches to thinking and problem-solving. It also equipped me with skills for communicating my ideas with those with different areas of specialization from myself.”

—Mel Ferrara ’15

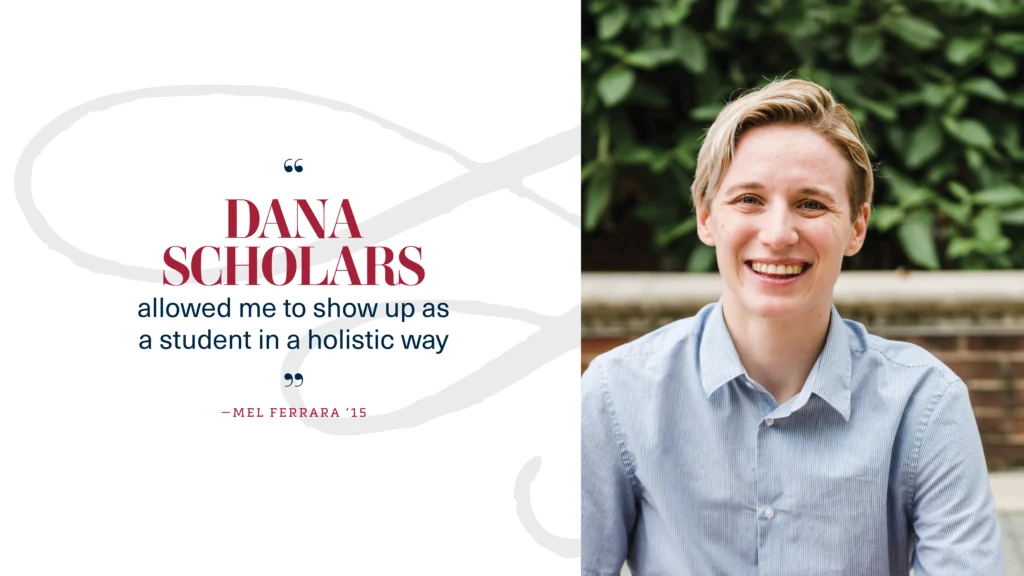

When Professor of Political Science Mohsin Hashim became director of Dana Scholars roughly 12 years ago, he wanted to promote the notion of engaged scholarship. “A Dana student should show civic initiative and see the linkages between how structures of power and knowledge are related,” he says.

Dana Scholars participate in shared seminars, independent research projects, internships and trips. This includes a second-year seminar on a theme chosen by the Center for Ethics (CFE) that applies to science, social sciences, humanities and the arts. “The CFE is our single largest intellectual investment on issues that transcend disciplines and delve into larger ethical issues,” Hashim explains. “We decided to connect our best and brightest students to larger questions and leading scholars and thinkers that the CFE brings in.” This experience further helps students explore Americans’ ethical obligations to their fellow citizens and how they think about their role as global citizens.

The opportunity to be part of a community of students who share a love for creative learning and innovation appealed to Mel Ferrara ’15, a gender and sexuality studies (which they self-designed) and philosophy/political thought double major. “Encouraging our collaboration deeply shaped my approaches to thinking and problem-solving,” they say. “It also equipped me with skills for communicating my ideas with those with different areas of specialization from myself.”

The most testing experience for the students is the final group thesis project during their senior year, which culminates in a public presentation at the Dana Forum symposium. “My teammates and I wrote about student activism and coalitional politics,” Ferrara says. “During our time at Muhlenberg, there was a specific rise in anti-racist activism, calling public attention to the extremely high levels of marginalization experienced by students, faculty and staff of color at our predominantly white institution. We wanted to use our project to contribute to an archive of student activism at Muhlenberg. Ultimately, completing it implored us to be deeply self-reflexive as white students as we navigated the complex terrains of the politics of archival work and storytelling.”

Not only did they learn time management, collaboration and being realistic about personal workload capacity—abilities that serve them today—the overall Dana Scholar experience helped Ferrara, now an adjunct instructor at Muhlenberg who recently successfully defended their Ph.D. dissertation, explore the relationships between academic work, innovation and teamwork. “As a first-generation college student, I’ve often felt uncomfortable with conceptions of college campuses as completely divorced from the ‘real world.’ This is a false dichotomy—one that is rooted in elitism and the exclusivity of higher education,” they say. “The program allowed me to show up as a student in a holistic way, highlighting awareness of both our positionalities and the importance of being engaged community members.”

Jessica Orofino ’21, a prehealth neuroscience major, didn’t know of RJ Fellows until she received a letter about the program the summer before her first year at Muhlenberg. “Community service has always played a pretty big role in my life, so it was the perfect opportunity,” she says. “I wanted to get to know the people in the areas I would be calling home for the next four years. I also liked the idea of being pushed to take courses outside of my general science comfort zone.”

Established in 2002 and funded in part by the generosity of the RJ Foundation, the RJ Fellows Program aims to help students understand and manage change and, through this knowledge, grow into leaders and agents of change, says Rich Niesenbaum, professor of biology and director of sustainability studies and RJ Fellows.

As seniors, students complete a fall capstone seminar as part of their culminating undergraduate experience (CUE) in which they examine an interdisciplinary topic related to the program themes of change, leadership and community engagement. In the spring, students develop projects that reflect these themes and present their work at the Senior Symposium.

During the Fall 2020 semester, seniors learned about plants in terms of their history; their use in design and engineering, medicine and pop culture; and the colonial nature of botanical exploration. The goal for the spring semester was to “bring about some meaningful change in our community and have it relate to plants,” Orofino explains.

“Throughout my RJ experience, I’ve been able to take courses that speak to change, how it comes about and what colors a change as ‘good’ or ‘bad.’ The most significant message I’ve taken from the combination of these courses is that change, and what it means for a community, seems to be based on whether the community wanted that change and how it was brought about,” she says. “So in thinking about that message, we faced the challenge of trying to decide on how to bring positive change to our Allentown community.”

The less structured project portion of the CUE in the second semester offers students a lot of freedom to explore issues and ideas related to the capstone theme that are important to them. “That’s a really cool thing. You don’t get that in any other course, and it gives us a lot of responsibility and also a chance to show ourselves what we’re capable of as both a group and as individuals,” she says.

Orofino says the RJ Fellows Program taught her to actively seek new perspectives that helped build a sense of responsibility for herself as a part of her community. “I can’t really say, ‘I can’t make a difference,’ or ‘I don’t know how to make a difference,’ because this program taught us all how, and I think that’s really important in the world we live in today,” she says.

“Community service has always played a pretty big role in my life, so it was the perfect opportunity. I wanted to get to know the people in the areas I would be calling home for the next four years. I also liked the idea of being pushed to take courses outside of my general science comfort zone.”

—Jessica Orofino ’21