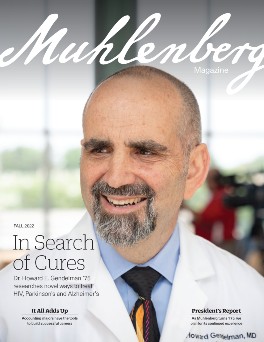

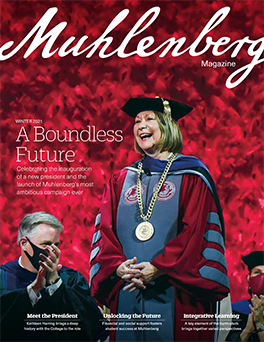

Meet the President

Kathleen Harring brings a deep history with the institution, a passion for the liberal arts and dedication to the Muhlenberg community to the position.

President Kathleen Harring began her role in an interim capacity in June 2019. When her official appointment was announced a year later, it was to a changed constituency.

“We are dealing with a global pandemic, a racial reckoning and a great political divide,” Harring says. “All of these events have affected individuals in our community in different ways, but they all deeply affect our collective community.”

Harring, the 13th president of Muhlenberg, has faced choices none of her predecessors had to make: How can the College protect the health of its community and its neighbors without making the Muhlenberg experience unrecognizable from what it was before COVID? What are the best ways to support a more-diverse-than-ever student body as acts of hatred against different marginalized groups surge across the country? How can the College promote the uptake of new, life-saving vaccines in a society rife with fear and misinformation?

Beneath the challenges 2020 introduced are ones that existed pre-pandemic. For years, higher ed professionals have been hand-wringing about the 2025 “enrollment cliff,” when a steep decline in the number of 18-year-olds graduating from northeastern high schools will mean a much smaller pool for northeastern colleges and universities to recruit from. A segment of the American population already questioned the value of higher education generally and the value of a liberal arts education more specifically.

But the value of a liberal arts education is, in part, that it develops the ability to comprehend and work toward solving complex problems. And Harring, a graduate of a small, liberal arts college herself, has spent her entire career teaching and promoting this multidisciplinary, expansive mode of education. She brings the same liberal-arts sensibilities to her tenure as president, and that has enabled her to lead effectively in uncertain times.

“When the opportunity arose for us to seek the next president to lead this wonderful institution, we found that leader prepared and ready to accept the challenge right here in our own community,” says Board of Trustees Chair Richard Crist Jr. ’77 P’05 P’09. “In short order, President Harring’s understanding of Muhlenberg’s unique campus culture, and her ability to move both the College and the community forward in unison, quickly demonstrated to the Board of Trustees that we had the right leader.”

A Deep History With the College

Harring grew up in a small town in Schuylkill County, about an hour and 20 minutes away from Muhlenberg. She had relatives in Allentown, the “big city” where her family would go school shopping each year. Her father took a year of premed classes at Muhlenberg before attending Temple Medical School. For her own undergraduate education, Harring chose Franklin & Marshall College, where she studied psychology. She completed a year-long research project with a faculty mentor, and when she arrived at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill for graduate school, she realized the uniqueness of her experience.

“None of my peers in my cohort did that. I had far more research experience than any of them,” she says. “And it really was due to being at a small liberal arts college where faculty worked with students on research.”

As a grad student, Harring discovered a passion for teaching. She tried to emulate her undergraduate professors: favoring discussions over lectures, collaborating with undergraduate researchers in her advisor’s lab. After earning her Ph.D. in social psychology, with a minor in quantitative psychology, she applied for faculty positions at small liberal arts colleges, and accepted one at Muhlenberg.

She joined the College as an assistant professor of psychology in 1984. She started out teaching introductory and statistics courses and went on to add classes in social psychology, the psychology of groups, health psychology, the psychology of women and gender and other special topics courses.

In 1993, Harring, an associate professor at the time, took over as chair of the Department of Psychology, a position she would hold through 2005. During her tenure, the department revamped its curriculum and hired a number of new faculty in response to a surge of interest in psychology among students.

“The new faculty we hired, many of whom are still here, were individuals who came in with different teaching strengths, different ideas and different types of research that really engaged the students,” she says. “When I started out in 1984, not as many faculty in the department were actively engaged in scholarship. Now, conducting research is so much a part of the student experience because the faculty are so creative and productive and our students ask such interesting research questions.”

Around the same time she became chair, Harring began a long-term research partnership with Professor of Psychology Laura Edelman. Following a sabbatical in the fall of 1992, Harring presented her work on social categorization and intergroup conflict to colleagues. Edelman, a cognitive psychologist who specializes in perception, approached Harring afterward to say that their work had many interesting intersections and to suggest a collaboration. Over the years, Harring and Edelman have co-authored three papers, given at least 20 presentations and mentored dozens of students.

“I have lots of ideas but am very disorganized. Kathy is very organized and very driven,” Edelman says. “We have presented so often together that at one workshop, I overheard a member of the audience note that we were so familiar with each other’s behavior that we automatically slid between speaking and letting the other person speak, taking the lead or stepping back. We have always had fun and we mesh extremely well.”

In 1995, Harring and then-Professor of French Kathryn Wixon co-founded, with colleagues from across campus, the Faculty Center for Teaching, now known as the Muhlenberg Center for Teaching and Learning. Harring co-directed the center with Wixon until 2006 and directed it solo the following year. Both educators had previously served on a teaching and learning group that planned summer faculty development programs and were interested in creating a center that provided such opportunities throughout the year.

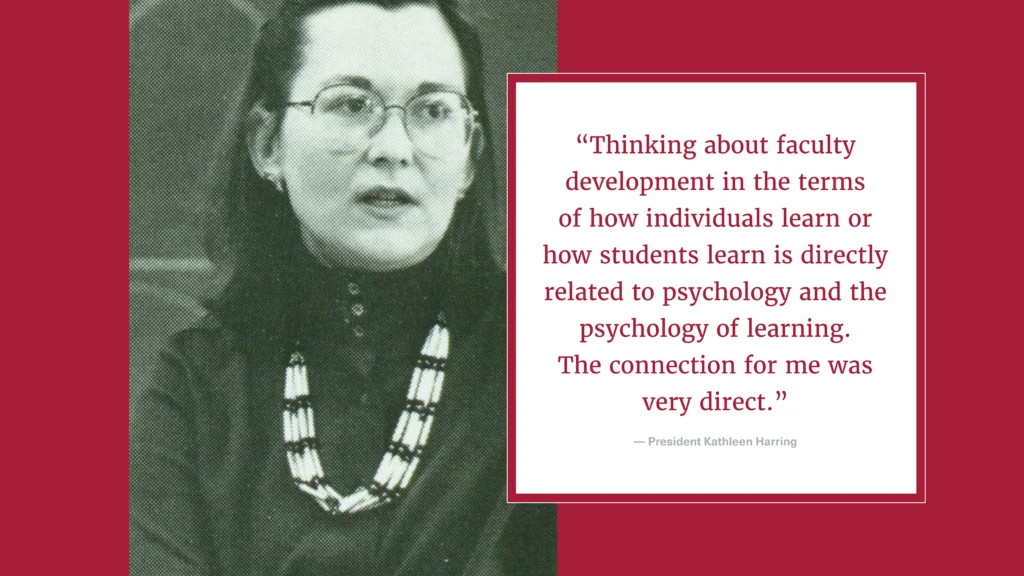

“Thinking about faculty development in the terms of how individuals learn or how students learn is directly related to psychology and the psychology of learning,” Harring says. “The connection for me was very direct.”

In 1999, Harring became a full professor. The following year, she shepherded her department’s move from the building now known as Walson Hall to the newly constructed Moyer Hall. During the planning phases, Harring collaborated with College administrators and staff as well as the architects to ensure that psychology’s new home would have space for meeting and collaboration (as Walson did) as well as state-of-the-art research facilities (which Walson did not).

“If you go over to Moyer, there’s that area on the second floor that’s right outside psychology, where there are tables and students hang out there and work and faculty are right there in their offices,” Harring says. “It was important for everybody in the department to keep that communal space for students.”

Teaching a Different Audience

Harring first took on an administrative role in 2006. Then-Provost Marjorie Hass created an associate dean for institutional assessment position in response to increasing standards for accreditation and assessment, and Harring says she was the only one to apply. She had been involved with a number of working groups on accreditation, so she had firsthand understanding of what would be required in this new position.

“It interested me because it involved bringing data together from all sorts of areas of the College to tell the story of Muhlenberg to the accreditors,” Harring says. “I’ve always viewed it that way: that it’s about telling our story in an empirically accurate and engaging manner.”

As associate dean for institutional assessment, Harring led the Muhlenberg group that was part of a multi-institutional grant from the Teagle Foundation to support assessment to strengthen senior-year experiences. As part of the grant, an assessment consultant conducted workshops for faculty and staff at each institution, and Harring says those workshops developed the College’s capacity to collect and use data to strengthen programs and the student experience.

“Kathy had an unusually rich grasp of the national higher education landscape and helped Muhlenberg stay engaged in what was happening beyond our own campus,” says Hass, who is now president of the Council of Independent Colleges. “As an early advocate for the importance of faculty development and assessment, she was an ideal person to invite into a leadership role.”

Harring continued teaching at least one class per year and working with Edelman and students on research even as she became dean of institutional assessment and academic planning in 2013. But in 2016, when she became vice president and dean of institutional effectiveness and planning and also filled the provost role in an interim capacity, she needed to step away from teaching.

“While I missed being in the classroom with students, it wasn’t so difficult because I viewed all of the work that I was doing, particularly in faculty and staff development and in assessment, as teaching,” Harring says. “I was just teaching a different audience.”

As provost, a position she held from 2017 to 2019, Harring co-chaired the College’s strategic planning process with former President John Williams. In addition to helping assemble and edit the final plan, she developed and oversaw the community planning process, in which nearly 60 different groups (including students, faculty, staff, alumni, parents and friends and neighbors of the College) shared their thoughts on Muhlenberg and its future.

“It was incredibly helpful to hear perspectives from all campus stakeholders. Interestingly, there was not that much variability across the groups,” Harring says. “It really appeared that there was a lot of agreement on what our strengths, areas for improvement, opportunities and challenges were.”

Harring also created the associate provost for faculty & diversity initiatives position, now held by Brooke Vick, and oversaw the implementation of inclusive hiring practices for faculty. She collaborated with the Office of Advancement to secure funding for what would become the Faculty Rising Scholars Program to support faculty scholarship, one of the goals outlined in the strategic plan, and authored the proposal for the $600,000 grant the College received from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation in 2017. She oversaw the revision of the integrative learning curricular requirement, a cornerstone of the Muhlenberg experience, as well as the initial planning phases of offering graduate degrees, another goal described in the strategic plan.

A Time of Great Change

Since Harring moved from the provost’s office to the president’s, the College announced the launch of its School of Graduate Studies and its first two master’s degree programs (in applied analytics and organizational leadership). That announcement took place in early February 2020. When the first cohort of grad students began taking classes that fall, they were fully online instead of the planned hybrid model—but the launch proceeded, despite the pandemic.

So, too, did this November’s public launch of Boundless: The Campaign for Muhlenberg, which began its quiet phase in 2018. Harring, Vice President for Advancement Rebekkah Brown ’99 and the Board of Trustees debated whether to change course on the campaign as COVID hit. Other institutions were pausing their campaigns or choosing not to start them. Muhlenberg decided to proceed, Harring says, and the campaign, so far, has exceeded all expectations.

During Harring’s tenure, the College has also been nationally recognized as a leader in digital pedagogy, thanks to the faculty development efforts that took place ahead of the Fall 2020 semester, and earned the 2020 Carnegie Community Engagement classification. Muhlenberg received its largest-ever gift from an individual, $7.5 million, which enabled it to break ground on its first new building in 16 years. And the College recruited its most diverse first-year student and new faculty cohorts in its history.

Harring, who is the first woman president of the College, is also technically history-making. While she recognizes the significance, she knows that other women and individuals from under-represented populations who have been “firsts” in other capacities at the institution have paved the way for her.

“What it means to me is that it’s incredibly important for us to have diversity and representation across all areas,” she says. “Learning, working and playing with others who come from different backgrounds makes us better humans and a better community. We know that diverse groups make better decisions because they are analyzing multiple perspectives.”

And the day-to-day decision-making required in a pandemic is significant, Harring says. Every plan she makes with senior staff requires a backup plan and, sometimes, a backup to the backup plan. The pandemic has been, and continues to be, a defining feature of her experience so far as president. Even her inauguration took place more than a year after the Board of Trustees announced her appointment to the role, and guests were required to mask indoors. Still, those in attendance celebrated her leadership so far and her vision for the future.

“In addition to [Harring’s] superb intellect, her genuine passion, her devotion to the liberal arts environment and her exceptional experience, she possesses something else that I find essential but is often missing in a new president—she knows us, understands us, believes in us and loves us,” says Curtis Dretsch, former professor of theatre and Harring’s longtime colleague. “She will be an extraordinary leader during a time of great change.”

These uncertain times have highlighted what is distinctive about the Muhlenberg experience, Harring says, and what the College needs to foster in order to weather the challenges, known and unknown, that lie ahead.

“My expectation is that there will be a very close integration of academic affairs and student affairs. Things that happen outside the classroom impact what happens inside the classroom and vice versa. Making sure we are providing students a holistic education means that the leaders in academic affairs and the leaders in student affairs, along with faculty and staff, are working closely together to support student success. I saw that integration deepen during the pandemic, and we have to continue that powerful, interconnected education,” Harring says. “I truly believe that we need more Muhlenberg graduates, individuals positioned to lead and serve and change our world.”