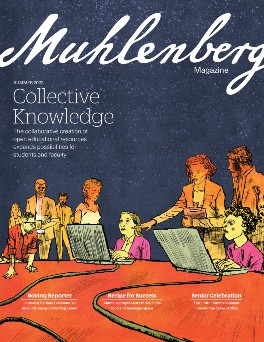

Open Books

The creation and use of free digital textbooks at Muhlenberg allow faculty to customize their course content and students to share their knowledge with scholars around the world.

Assistant Professor of History Tineke D’Haeseleer teaches a course called China’s Magical Creatures (and Where to Find Them): “The whole course is set up to be a different kind of history of China, looking at the strange and the weird,” D’Haeseleer says. “It’s a cultural history. You need a little bit of background on the regular timeline of the dynasties and the emperors, but you’re putting all of the strange stuff in the foreground, and no textbook does that.”

Right before the Spring 2019 semester, she learned that the College supports the creation of open educational resources (OERs), online materials with openly licensed content that is free for other scholars to use, adapt and share. She decided to build an OER for China’s Magical Creatures that semester, with each of her students authoring a different chapter on a topic of their choosing as their final project.

“They got really into it,” D’Haeseleer says. “They said, ‘I never get to show things to my parents or friends. Now, I have something that doesn’t disappear.’ This [project] made them create something they could be proud of. Students had to pull out the stops and really make it shine.”

“[OERs] allow for students to be co-creators in their educational experience.”

Provost Laura Furge

The experience was such a success that she worked with her Korean History students to create an OER for that course as well, and worked with students in both courses in later semesters to create content for a second edition of each OER. She has also used the student-created chapters in her teaching. For example, one that made an impression in Korean History this spring was a chapter Ale Cepeda ’23 wrote in Spring 2020 on the civilians’ perspective of the Korean War.

“I’m so glad she wrote about that. Usually students come in with a little bit of knowledge about U.S. participation … but rarely get to think about the human toll,” D’Haeseleer says. “Perhaps the current war in Ukraine made [students] more sensitive to it, but the chapter is a welcome supplement to any dry textbook narration of high politics and military maneuvers.”

The student-coauthor model is just one way Muhlenberg faculty are utilizing OERs. Some are building their own OERs from scratch. Others are utilizing OERs (or parts of them) created by peers at other institutions. Often, OER adoption eliminates the need for students to purchase a costly textbook, but this is not the primary motivator for the College’s embrace of OERs, says Provost Laura Furge.

“OERs allow the instructor to bring information on topics to the class in the order and style they would like,” she says. “And, they allow for students to be co-creators in their educational experience. The very first thing in our mission statement is that we want to develop independent critical thinkers. [Students] need to be evaluating what kinds of resources go into an OER, why it’s valuable and how to present that information and have others engage with it. OERs embrace all of that.”

Finding Digital Solutions

Muhlenberg’s digital learning team, which supports faculty in the creation and adoption of OERs, was established in 2014, but it’s difficult to pinpoint a moment when OERs came onto the College’s radar.

“For many years, faculty in a variety of departments have been concerned about the cost of publishers’ textbooks as well as concerned or dissatisfied with the limitations of those textbooks,” says Dean for Digital Learning and Professor of Media & Communication Lora Taub. “Many faculty really have been creative in searching for ways to provide affordable solutions to course materials for students and course materials that meet their teaching and pedagogical needs.”

Sometimes, that means relying on digital resources from Trexler Library, another major partner in the College’s OER effort. Other times, it means making PDFs of individual chapters of a textbook available through Canvas (the College’s online course management system) in accordance with copyright protections. The third way to achieve these goals is to utilize openly licensed and freely available educational resources on the web—OERs.

OERs can be built on a variety of platforms. Muhlenberg uses Pressbooks, a WordPress-based platform that allows for the creation of chapters and the embedding of videos, interactive activities and other multimedia. Content from Pressbooks can also be imported into Canvas so students can find everything they need for a course—their “textbook,” assignments, quizzes and discussion boards—in one place. Most OERs are formatted to work equally well on a computer, phone or tablet, to be printed easily and to be read by accessibility readers. And because OERs are published openly online, users are able to provide reviews, comments and suggestions for revision.

“OERs are peer-reviewed, and they’re peer-reviewed openly. In some ways, they’re subjected to a more rigorous review [than traditional textbooks] because it’s not limited to the one or two reviewers that a publisher selects,” Taub says. “Just because it doesn’t look like the dominant academic publishing model doesn’t mean it’s deficient.”

OERs at Muhlenberg

The open licensing of OERs means faculty can pull in bits and pieces of a variety of OERs and edit those pieces as needed to build something appropriate for their courses. If faculty can’t find what they want, the College supports those who wish to produce an OER from scratch.

Associate Professor of Italian Daniel Leisawitz and Lecturer of Italian & French Daniela Viale were the first at Muhlenberg to do so. For years, they’d noticed that their entry-level Italian textbook was getting pricier with each new edition, but they couldn’t find viable alternatives on the market. Five years ago, they decided to take on the challenge of creating their own OER textbook.

OERs often utilize Creative Commons licenses or similar open licenses, which means everything an OER author uses has to be available to be shared. For Leisawitz and Viale, this meant not only writing the text but also traveling to Italy to take their own photographs and partnering with Italian videographers to produce digital audiovisual content. They gave that material to Senior Instructional Design Consultant Tim Clarke and then-Digital Learning Assistant Jarrett Azar ’20, who began formatting it in Pressbooks in the summer of 2018. That fall, after a full summer’s worth of work, Spunti: Italiano Elementare 1 was ready for use in class. (That semester, Leisawitz and Viale created Spunti: Italiano Elementare 2, which was first used in the spring of 2019.)

“The student response has been overwhelmingly positive,” says Taub, who estimates that these resources have saved Italian students approximately $58,000 on textbook costs since they first debuted. “Students recognize that they’re working with a textbook created by their professors and that’s exciting. The examples in and the content of the textbooks are highly relevant because the professors have shaped them for Muhlenberg students. Students’ input and feedback is helping to inform future revisions of the textbooks.”

Since then, Muhlenberg faculty and students, with the help of colleagues on the digital learning team and in Trexler Library, have created complete OERs in philosophy, political science, French and history. (Taub says that other colleagues “have been doing this work very effectively on their own,” so this is not a complete list.) While faculty across the disciplines are utilizing OERs to different extents and in different ways, the Department of Languages, Literatures & Cultures is among the leaders in this effort.

“All languages are exploring the use of OERs on some level,” says Department Chair and Associate Professor of Spanish Erika M. Sutherland, noting that the success of the Spunti products showed Leisawitz and Viale’s colleagues what was possible. “Textbooks are not as agile as an OER. They aren’t as up to date. They tend to stay away from hot-button issues. These are the things that connect with students.”

Visiting Lecturer of German and Women’s & Gender Studies Julie Shoults has been part of a pilot program to use Grenzenlos Deutsch, an introductory OER for German language students created by colleagues at other institutions, for the past three years. The first time she used it, Clarke helped her set up the OER and its supplementary activities in Canvas. At the start of each semester, she arranges the material in Canvas to suit her needs and adds in additional activities for her students to complete each week before coming to class. It’s a lot of work up front, she says, but the OER’s strengths are apparent, especially when she compares it to the textbook she uses for intermediate German students.

“This textbook really falls short on diversity, but the OER is fantastic. It includes the idea that German is not just a bunch of white German people speaking one form of German,” she says, noting that the OER is centered on Austria and depicts both native and non-native speakers. “That made me very aware of the shortcomings of the other book [for intermediate students]. I find myself supplementing it more and more with online materials that are all free.”

Authors and publishers of any work must choose which information to include and which to omit as well as how to present that information. With a textbook, those decisions are set in stone for at least a few years, until the next edition is printed. OERs allow for instantaneous, ongoing revision to bring in current events and newly discovered knowledge.

The use of OERs also “empowers students to be not just receptacles of information but to think about who controls knowledge generation, who gets to contribute and have a voice and what is important to be talking and thinking about,” Furge says. “It brings the students further alongside their faculty members rather than a top-down approach.”

Taub says the traditional academic publishing model serves as a gatekeeper that often shuts out diverse voices. For example, a 2018 study from the Journal of Communication analyzed journal article authors in the field of media studies and found the majority of published authors in mainstream academic journals were white men. The issues Shoults identified in her intermediate German textbook—namely, its centering of the experiences of white, heteronormative families—are similar to issues that plague traditional textbooks across the disciplines.

“We are, as a department and as a college, looking to decolonize our curriculum and move away from a white, male, European-dominated curriculum,” Sutherland says. “As a college, as we work to make our curriculum more global, more equitable and more diverse, those packaged textbooks have to become a thing of the past.”

“As we work to make our curriculum more global, more equitable and more diverse, those packaged textbooks have to become a thing of the past.”

Support and Leadership

Muhlenberg’s support for OERs takes many forms. The digital learning team, which includes student digital learning assistants, provides workshops to faculty and students interested in adapting existing OERs and/or creating their own.

Digital Learning Assistant Rachel Bensimhon ’22 developed a love for OERs after counseling faculty working on open-access projects: “I help them go about seeing these things from a student’s point of view,” says Bensimhon, who is continuing her work with the digital learning team this summer. “When professors enlist students as collaborators, learning becomes much more active and engaging.”

The College pays for a subscription to Pressbooks and provides grants to support faculty development related to OERs, including for participation in College-run, OER-centric learning communities. Clarke has now designed and led two such learning communities; for the most recent, this spring, he invited faculty to come in with project ideas and then customized the workshops to their needs. Recently, Muhlenberg received $22,000 from the Pennsylvania Consortium for the Liberal Arts to support the OER initiative. The College is also part of the American Association of Colleges and Universities’ 2021-22 Institute on Open Educational Resources.

To continue leading in this space, Taub hopes that, in the next five years, Muhlenberg is able to provide a number of textbook cost-neutral courses and to “make more visible the creative model that engages students as collaborators in OER creation.”

“Like our other areas of digital learning, it’s not technology for technology’s sake,” Taub says. “It’s another initiative where we are deeply committed to exploring the uses and possibilities of digital learning in service of our larger institutional priorities and goals, particularly around access, affordability, diversity, equity and inclusion.”