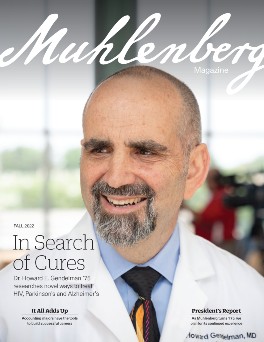

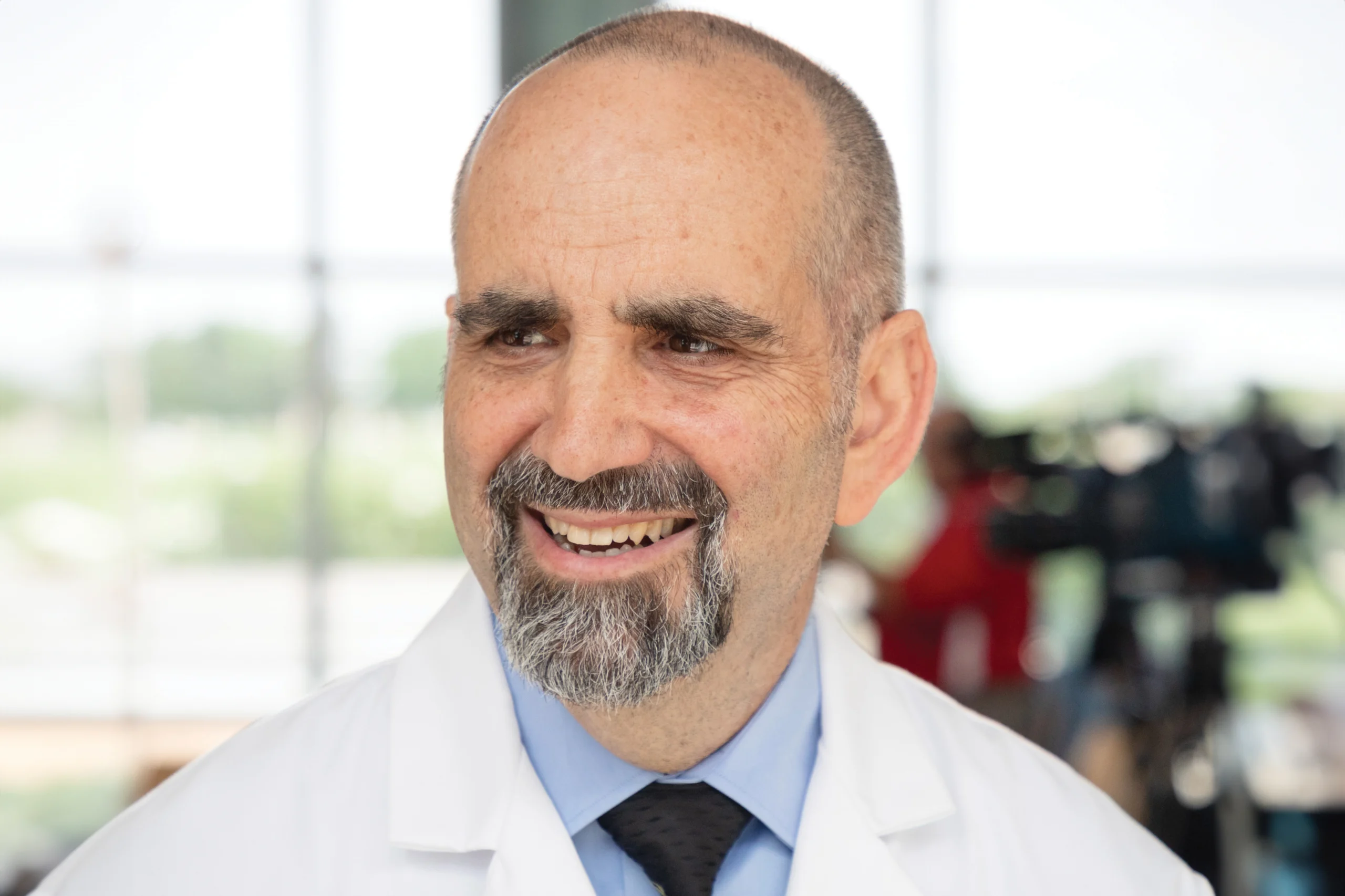

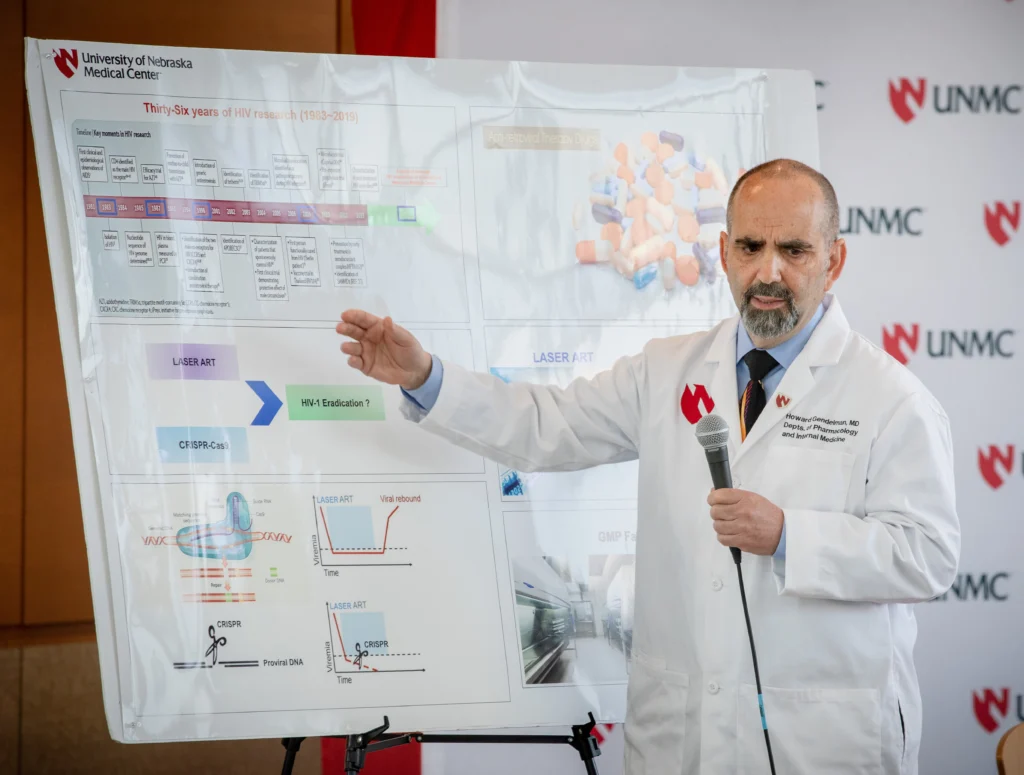

Dr. Howard E. Gendelman ’75, working with Temple University Medical Center scientists, achieved the first elimination of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) from live animals, a breakthrough that came nearly four decades after the HIV epidemic began. The study, published in Nature Communications in 2019, used a combination of two approaches to eliminate latent virus in infected mice: a gene-editing therapy and a long-acting antiretroviral therapy.

Gendelman’s lab has since modified the latter therapy into ultra-long-acting (ULA) antiretroviral therapy, medicines that are planned to enter clinical trials in humans in 2023. ULA therapy is a different way of delivering existing antiretroviral drugs, which approximately 28.7 million HIV-infected patients around the world take daily to prevent the virus from progressing into AIDS. The difference is that ultra-long-acting antiretroviral therapy could be administered as an injection every six months, and it could potentially be used to prevent infection in HIV-negative individuals. (Approximately 1.5 million individuals worldwide acquired HIV just last year.) If effective, the injection would be as close as scientists have come to finding a vaccine against the virus.

“ULA therapy started off with a need. Patients have to take pills every day. If they forget to take them, the virus rebounds,” Gendelman says. If clinical trials pan out and enough infected and at-risk individuals could get the ULA therapy injection, “HIV will go away. That’s what we’re going to try to achieve.”

HIV has been among Gendelman’s major scientific interests since the beginning of his career as a scientist. At Muhlenberg, he studied natural science, Russian studies and classical guitar before heading to medical school at Penn State-Hershey Medical Center. After a few years of practicing medicine, he studied neuroscience at Johns Hopkins, where he first learned to do research. He worked at the National Institutes of Health and then the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research before joining the University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC) in 1993.

Today, he’s UNMC’s Margaret R. Larson Professor of Internal Medicine and Infectious Diseases, founding chair of UNMC’s Department of Pharmacology and Experimental Neuroscience, the editor in chief of the journal Neuroimmune Pharmacology and Therapeutics and the co-founder of the biotechnology company Exavir Therapeutics, Inc. His broad research interest is in neurodegenerative disorders, a category that includes the neurological manifestations of HIV as well as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases. According to Web of Science, which tracks high-quality scholarly citations, Gendelman’s work has been cited more than 13,000 times, putting him in the top quarter of all scientists in terms of citations.

“Most people who go to medical school become doctors. That’s why you go to medical school. I did four other things … First, I am a physician, and second, a scientist. Being a scientist is something I learned later. Third, I became an entrepreneur — I co-founded a successful biotechnology company. Fourth, I am an inventor and leader,” Gendelman says. “I’ve done a lot of things, and I think that kind of basis was set during my time at Muhlenberg. You can really do anything you put your mind to.”

Formative Experiences

Gendelman came to Muhlenberg partly because of its strong premed reputation, but he wasn’t sure whether he’d be able to get into medical school. So, he supplemented his science classes with courses in Russian and music. Guitar was an instrument he’d never played prior to college.

“I was able to do things I was even more interested in than science. I became a really good guitarist. I learned how to speak and converse in Russian,” he says. “Those experiences stayed with me for the rest of my life and did make a big impact in the sense of being able to do what I wanted, when I wanted.”

One thing he wanted to do was spend some time in Russia, which he was able to arrange with help from Professor Ardvis Ziedonis ’55. Gendelman traveled there on a fellowship in 1973, during the height of the Cold War. He remembers his time in Russia as one of the most transformative experiences he had as a college student.

After completing medical school in 1979, Gendelman went on to a residency in internal medicine, neurology and infectious diseases at Albert Einstein College of Medicine’s Montefiore Hospital in the Bronx. During that time, he read a newspaper article about research happening at Johns Hopkins on lentivirus, a genus of viruses that has an association with multiple sclerosis. That interested him so much that he went back to school at Hopkins to become a scientist.

He continued his research into lentivirus, but he made almost no money and was prohibited from “moonlighting” as a physician to earn more. He also had three children. He accepted a job at a private practice in Westchester County, New York, to better support his family. But an important discovery would change his path.

“I was doing my last experiments with these viruses that were associated with multiple sclerosis, and it turned out that I ended up contributing to classifying HIV. [I discovered] that the viruses I worked with at Hopkins were the parents of HIV,” Gendelman says. “I really didn’t know what to do, because this was very early on and AIDS was a really big thing in the early ’80s.”

This discovery caught the eye of the then-new director of the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Anthony Fauci: “He called me up and said, ‘Look, you have all this background, you need to come to the NIH and continue your work here,’” Gendelman says.

That’s what he did: Over the next three years, Gendelman contributed to discoveries about the biology and the neurological manifestations of HIV. The team’s ultimate goal during that time was a vaccine, which still has not come to fruition decades later, partly because of the unique properties of the virus. He left the NIH in 1985 for a research and teaching position at Walter Reed, where he continued his HIV research.

“I was able to do things

[at Muhlenberg] I was even

more interested in than science. Those experiences stayed with me and did make a big impact in the sense of being able to do what I wanted, when I wanted.”

To the Midwest

In 1993, the University of Nebraska courted Gendelman to come to Omaha to help build up its medical center. At the time, it was nothing more than a community hospital. Today, it’s a complex with more than 60 buildings known for its highly ranked primary care program and its proportion of graduates practicing medicine in rural areas (it’s ranked seventh in the nation for both).

Gendelman’s research utilized fetal stem cells, and in 1999, he found himself at the center of a controversy. Upon learning of his work, antiabortion activists — including a prior governor — demanded that UNMC stop the research. Protesters targeted Gendelman’s lab and home.

“It wasn’t great,” Gendelman says of that period. “I couldn’t leave my position. I didn’t want to be seen as running away from something, and I helped build the place. We stuck it out. The university was very much behind us.”

That firestorm led to the creation of the nonprofit organization called the Nebraska Coalition for Lifesaving Cures. The organization has spent more than 20 years lobbying against attempts to restrict biomedical research and therapies that utilize stem cells in the state of Nebraska.

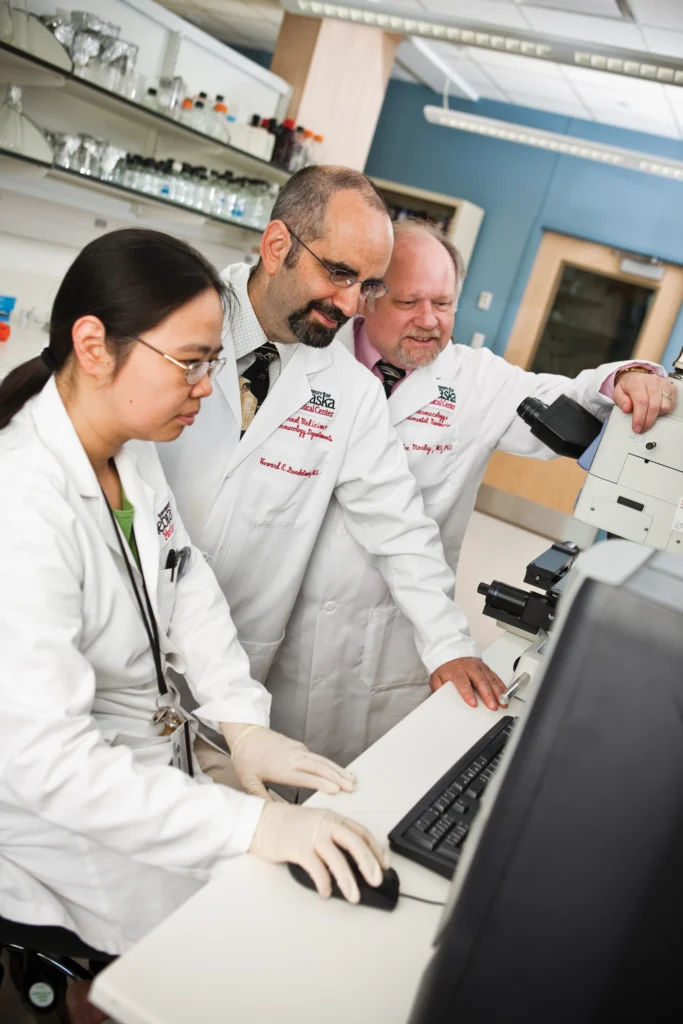

Gendelman’s research would continue to evolve, sometimes inspired by his students. He recalls a smart M.D/Ph.D. student in his lab in the early 2000s who wanted to work on Parkinson’s disease, which, at the time, Gendelman knew very little about. The two learned about Parkinson’s together, and after a series of failed experiments, they started making progress. Gendelman’s lab continued studying the disease after the student left and uncovered some important connections between Parkinson’s and HIV.

“The immune system plays a major role in Parkinson’s disease,” he says. “We discovered that there were immune system dysfunctions in Parkinson’s disease that involve the same cell that’s affected in HIV, a type of lymphocyte.”

Gendelman would go on to found UNMC’s Center for Neurodegenerative Disorders in 2009, a center that’s focused on understanding the causes of diseases like Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s and HIV in order to bring about potential treatments and cures. The aforementioned discovery, for example, led Gendelman to try an existing drug, sargramostim, to treat the Parkinson’s-affected immune system. In a clinical trial that began in 2013, the drug was found to halt the progression of Parkinson’s disease in patients who received it. Gendelman’s team is currently helping to recruit hundreds of patients for a study that could lead to FDA approval.

Dares and Discoveries

Around the same time he began studying Parkinson’s disease, UNMC offered Gendelman a promotion to department chair. Pharmacology was open. The dean said, “You can’t be department chair and know nothing about the department. Let me send you for a refresher course.”

“He was sending me to a remedial course for second-year med students that flunked pharmacology,” Gendelman says.

Instead of moving forward with that, Gendelman offered a proposition: Make him chair of the department (which would be rebranded as the Department of Pharmacology and Experimental Neuroscience) and, within a year, he’d create a new field (neuroimmune pharmacology), write a textbook on the subject, help establish a society and start a new journal. If he could do it, UNMC would have to make him a named professor. If he failed, UNMC could find someone else to do the job. The dean accepted the bet.

Out of that wager came the textbook Neuroimmune Pharmacology, the Society on Neuroimmune Pharmacology and the Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology, with Gendelman as editor in chief. That’s also when Gendelman earned the title he has now, as the Margaret R. Larson Professor of Internal Medicine and Infectious Diseases. Previously, UNMC’s Department of Pharmacology had been ranked 89th in the nation in terms of how much funding it received from the NIH. Within five years of Gendelman taking over as chair, the Department of Pharmacology and Experimental Neuroscience was ranked in the top 10.

“I like dares,” Gendelman says. “When people say ‘you can never do it,’ it gets me going.”

This has been relevant in his research on HIV, which has continued throughout his career. He created mice with humanized immune systems that were ideal for studying different treatment options for HIV. That was one reason he got connected with the research team at Temple University that would co-lead the groundbreaking 2019 study in which the scientists eradicated HIV from these humanized mice. The NIH actually denied Gendelman and his co-author funding for that study because they didn’t think it would work.

It did, and now both of the treatments that study utilized in mice are making their way into humans: This year, the gene-editing therapy began clinical trials, which are being led by Temple University scientists, and the ultra-long-acting antiretroviral therapy, co-developed by Gendelman, will begin trials next year.

Gendelman also co-founded a biotech company, Exavir Therapeutics, Inc., which is developing its own gene-editing therapy, currently in preclinical trials, to improve efficacy and safety. Starting the company “was a dare: I’ll never be able to find a product and bring it to humans. Very few people can do it. Big companies can do it, but not individual scientists,” he says. “We wanted to move our inventions to people … Having a company would be really important then.”

“My dreams are now

literally inches from

reality. [My team and I]

have discovered the means

to halt HIV transmission.”

Continuing to Innovate

Throughout this time, Alzheimer’s disease has also been on Gendelman’s radar. This has been more difficult to study in animals because “there’s no such thing as a demented mouse,” Gendelman says. His lab has been busy developing a mouse model in which they can study the effects of Alzheimer’s disease and the possibilities of different treatments. That technology is now at a point where Alzheimer’s itself will be able to be more directly studied in his lab.

Gendelman was able to continue practicing medicine until a few years ago, when he realized he couldn’t do it all. He’d been a physician for 35 years at that point, and was also writing books, serving as editor in chief of a journal, teaching grad students and medical students and playing music during his free time. His lab publishes “major scientific findings every few months,” he says, and he has 12 graduate students working with him at any given time.

This April, the Nebraska Coalition for Lifesaving Cures, the nonprofit organization founded to defend stem cell research like Gendelman’s, presented Gendelman and his wife, Dr. Bonnie Bloch, with the 2022 Life Saver Award. But if Gendelman’s discoveries continue to prove safe and effective in human clinical trials, most of the life-saving he’ll do is still ahead of him.

“I am blessed in the fact that two of my dreams are now literally inches from reality. [My team and I] have discovered the means to halt HIV transmission and developed new medicines … [that will] perhaps someday in the not-so-distant future help make a world that is HIV-free,” Gendelman says. “This would be enough for nearly anyone, but for us, it was just a start, as we worked in parallel on a separate road to halt and perhaps even reverse the maladies of Parkinson’s disease. A similar path was taken and the results show parallel successes. My experiences; my colleagues Benson Edagwa, R. Lee Mosley and Alborz Yazdi; and my life of learning have led me through that door and I feel blessed to have lived this life.”